Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

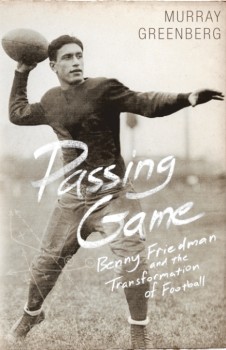

The Hebrew quarterback who changed football forever

By Murray Greenberg

For Jewish boys in Cleveland and other cities, football had an added

element of cool. Playing football was a great way to fit in. It was also a perfect

antidote to the anti-Semitism and vulgar stereotypes that accompanied

the influx of European Jews into American cities. Jews were “the polar opposites

of our pioneer breed,” wrote E. A. Ross, a noted sociologist of the

day. “Not only are they undersized and weak-muscled, but they also shun

bodily activity and are extremely sensitive to pain.” What better way to debunk

such venomous stereotypes than to embrace the physicality and violence

that football offered? No matter that the violence of the game was

precisely what the parents of these boys found most offensive. Shooting a

few baskets or taking a casual swim at the Jewish Center was fine as far as it

went, but these boys needed more.

The football genie began to woo young Benjamin Friedman while he was

in grammar school, just another neighborhood runt with grandiose dreams

of all-American glory. For him and other inner city boys, because fields and

parks weren’t always available, the road to the all-American team sometimes

began, quite literally, on a road. On narrow side streets, in the cold

mist blowing in off Lake Erie just a mile or so uptown, the boys practiced

the moves they imagined had been used by such college football legends

as the University of Chicago’s Walter Eckersall and Michigan Wolverine

Willie Heston. Depending on the particular street, sometimes the best interference,

or blocking, for these future stars was a tree trunk sitting on a

lawn on the side of the road.

Poor facilities weren’t the only obstacles these young Jewish kids had

to deal with. Unlike their gentile counterparts who were more or less free to

grab a football the moment school let out, Jewish boys spent the better part

of their afternoons in Hebrew school—cheder in Yiddish. Hebrew school provided

the kids, who were quickly adapting to secular culture, with a little

religious balance. But many of them, Benny included, weren’t particularly

interested in that, as he recalled years later: “I couldn’t wait to get over

[Hebrew school] so that I could be free and play with the rest of the kids.”

What active adolescent boy wouldn’t prefer pickup football to cramming

into a small, unventilated room to learn Hebrew from a rabbi who tended

to discipline misbehaving students with the business end of a stick?

Benny’s Hebrew school crucible ended mercifully, if somewhat painfully,

when he was twelve, thanks to a fellow student’s prank. One day, as the

class stood up to recite prayers, a loud thud interrupted the proceedings.

The kid next to Benny had knocked his prayer book out of his hand. A

moment later there was the sound of another thud. It wasn’t another book.

It was the sound of the teacher’s stick smashing into Benny’s back.

“Pick it up,” the teacher barked at Benny.

“I didn’t knock it down,” Benny said.

Benny’s reply didn’t mollify the old rabbi. Once again his stick crashed

against the boy’s back. “Pick it up,” he again commanded.

Benny wouldn’t give in, despite the two painful blows and the promise

of more to come.

“I won’t pick it up,” the boy cried. The old man rained down his stick

on Benny’s back a third time.

The rabbi’s brutality didn’t persuade Benny to pick up the book. But

the three welts that Lewis and Mayme saw on their son’s back when he

came home persuaded them to remove him from the Hebrew school.

If Benny had known that the rabbi’s corporal punishment would have

prematurely ended his formal religious education, he gladly would have taken

another three cracks to the back. Now he had more time for after-school

football.

He also had more time to pursue his other passion—bodybuilding. Becoming

the next Jim Thorpe, the Olympic track and field champion and

superstar footballer, wasn’t enough of a dream for young Friedman. He also

wanted to become the world’s strongest man. The boy was a fanatic. He

read magazines on bodybuilding techniques. He attended traveling strongman

shows. He entered and won local strongman tournaments.

Mostly, though, Benny exercised indefatigably, crafting a unique regimen

that included but went far beyond the usual barbells and dumbbells

and medicine balls. “We had an iron brick that weighed forty-nine

pounds and it was a trick to be able to pick that up by the side and turn it

over and hang onto it and muscle it up,” Benny said later. The other part of

the “we” was a big Irishman named Sweeney, a janitor in Benny’s grammar

school. Sweeney worked with Benny in the school’s cellar and taught

Benny the trick.

Benny also learned to lift a heavy chair by the tip of a leg and toss the

chair from hand to hand. Sometimes he’d lift a heavy broom from the tip

of the handle. One particularly unorthodox move in Benny’s repertoire involved

his right hand and a one-armed desk. “I’d stretch my hand and

stretch my hand till I could get it all the way across [the desk] so that I was

able to make a 180-degree spread between my thumb and my little finger

and have this big spread between my first finger and my thumb,” Benny

said later.

Benny liked these unusual exercises not only because they began to

produce a strongman’s power and muscles, but also because—maybe more

so because—there was an intellectual component to them. He was a smart

kid and liked figuring out the “tricks” involved, in thinking through the

leverage and angles that were as necessary to the performance of the maneuvers

as was brute strength.

When Benny entered Fairmount Junior High, he received some formal

football instruction for the first time. There was no football team at Fairmount,

but there was Howard Gehrke, a gym teacher who was happy to

teach the boys certain fundamentals that in later years he’d display as a

Harvard fullback. Gehrke gave Benny and his classmates their first lessons

on how to fall on the football, how to tackle, and other fine points they’d

given little or no thought to while playing in the street. (Less than a decade

later, another Fairmount student named Jesse Owens would catch the eye

of a Fairmount coach and receive his first instruction in his chosen sport.)

Gehrke’s emphasis on fundamentals literally and figuratively took the

game off of the street for Benny. The gym teacher gave Benny his first

glimpse at the technique and strategy of the game. The boy began to understand

that football, as violent and physical as it is, was also a thinking

man’s game, and he liked that. The game was far more intellectually stimulating

than the challenges involved in becoming a strongman, which, aside

from a creative exercise here and there, were limited to endless chin-ups

and the repetitive hoisting of heavy weights. As high school beckoned,

Benny abandoned his strongman ambitions to devote himself to football.

He entered the ninth grade at East Tech High, and he entered a new world

when he came out for coach Sam Willaman’s football team.

Willaman’s football pedigree was impressive. He’d been a star fullback

for the mighty Ohio State Buckeyes. Now, as East Tech’s coach, he played

professionally in his spare time with the Canton Bulldogs alongside none

other than Jim Thorpe. “Sad” Sam Willaman (so known for the naturally

dour expression branded on his face) had built East Tech into the scourge

of the Senate, and he had multiple championship trophies sitting in his office

to prove it. And his 1919 group had enough talent to field two all-star teams.

It didn’t take Benny long to realize that the East Tech football scene

wasn’t Mr. Gehrke’s gym class. The second coming of Walter Eckersall and

Pudge Heffelfinger and Jim Thorpe and Willie Heston would have to wait.

Friedman would need to watch and learn, and he’d have to grow, too,

because even with his strength he was still, as he would say, “just a little

kid,” about five foot six and not even 150 pounds. So Benny spent his ninth

and tenth grade seasons on the scrub team, watching East Tech’s talented

varsity players, eagerly learning fundamentals, and building up his body.

With the wisdom of a dedicated apprentice and a bit more size and

muscle, Benny, now a junior, reported for tryouts for East Tech’s 1921

team. He was developing into a fast and agile player, clever with the ball,

and strong, much stronger and tougher than his modest frame suggested.

He was also good, unusually good, at passing the big round watermelon

they called a football in those days. All the weight training and chair tossing

and hand stretching he’d done had unwittingly paid off: Benny could

wrap his hand around the ball, cock it behind his ear, and throw it, accurately.

He didn’t merely place the ball in his palm and heave it like most

everyone else.

Unfortunately, Sam Willaman couldn’t see past Benny’s size, or, more

to the point, lack of size. A year earlier, Willaman’s undefeated team had

steamrolled its way to the Cleveland city championship and into a national

championship game against Washington state’s Everett High School. The

boys from Washington were bigger than the invaders from Ohio by about

twenty pounds per player, and they asserted that advantage to bang out a

bruising 16–7 victory. Willaman was determined to “get bigger” for the

following season. The still-undersized Friedman wasn’t what the coach had

in mind.

“You’re too small to play for us,” he told Friedman. “You should transfer

to Glenville High if you want to play football.”

Willaman might have thought he was doing the youngster a favor by

steering the young Jewish player to Glenville, a far weaker team than East

Tech with a roster liberally sprinkled with Jewish players.

Sad Sam Willaman didn’t realize he’d also just made the biggest mistake

of his coaching life. Many years later, a high-school basketball coach

in North Carolina would make a similar mistake, cutting a sophomore

who was “too small” to play. The boy’s name was Michael Jordan.

In 1922, Friedman humbled his old team with passes, embarrassed

it with trick plays, and buried it with four touchdown runs that

included jaunts of forty-two and thirty-five yards. The long scoring runs

dazzled East Tech, but for pure devastation there was his shortest touchdown,

a one-yard exclamation point to a ninety-nine-yard drive that saw

the Tarblooders bully the six-time Senate champs from goal line to goal

line. It was the drive that signified a change in the balance of power in

Cleveland high-school football, a drive that just a year earlier would have

been unthinkable.

Benny’s performance once and for all debunked Sam Willaman’s

gloomy forecast of his football future. It also erased any lingering doubts

about the Tarblooders’ bona fides. They were for real, undefeated and

nearly unscored upon, and in first place in the Senate.

Next for the kid who was too small to play for East Tech would be a game

against longtime Illinois power Oak Park for the mythical national high school

championship. Glenville was new to such rarified

air and had every reason to be skittish. But the scoreboard

at the end of a hard-fought game read Glenville 13, Oak Park 7.

Benny had done what the great Red Grange of Wheaton couldn’t do. The

upstart school from the Jewish ghetto was a national champion.

From the book Passing Game by Murray Greenberg. Excerpted by

arrangement with PublicAffairs (www.publicaffairsbooks.com), a member of

the Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2008.

~~~~~~~

from the Februrary 2009 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|