Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

Book Review

By Jay Levinson

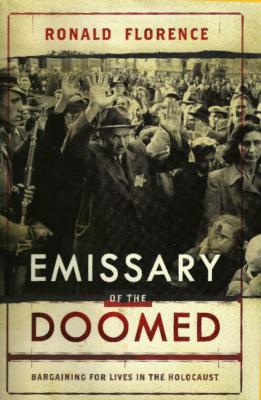

Emissary of the Doomed: Bargaining for Lives in the Holocaust

by Ronald Florence

New York: Viking/Penguin Group (2010)

ISBN: 978-0-670-02072-0

25 April 1944. Yoel Brand was enjoying the last vestiges of café life in Budapest. The Germans had invaded the city, and a new reality was taking over. Brand was active in the Vaada, the Jewish community organization, and he was privy to inside information. Two Jews had miraculously escaped Auschwitz, and in Budapest they gave clear testimony to what had happened to the thousands of Polish Jews who had disappeared. There was no resettlement in the East. There was no incorporation into the German economy. There were only gas chambers and corpses. The two escapees brought further news. A new crematorium was under construction to annihilate Hungarian Jews at the rate of 12,000 per day.

Brand was a “macher,” making business deals in the cafés, dealing with all segments of society ranging from respectable businessmen to sleazy Gestapo types who were paid off with “inducements” to let business proceed, even under Nazi occupation.

On this Spring day Brand’s life changed dramatically. He was suddenly whisked away by the Germans and brought to a small suburban villa. Brand fashioned himself a great negotiator, able to conduct business and cut deals. Brand entered the villa, and the person in charge offered a startling suggestion. If Brand could arrange transfer to the Germans of 10,000 trucks and other materiel, one million Hungarian Jews would be saved. The Nazi offering the deal was Adolph Eichmann, whom Ronald Florence describes as a man of ordinary features with a penchant for horses, fancy cars, women, and a good drink when times were tough. He was obsessed with order and efficiency, and had a keen desire to rise in the Nazi hierarchy.

This book is a careful examination of Brand’s efforts to respond to Eichmann’s offer. He met with the Nazi for further details, then he traveled to Istanbul with Bandi Grosz in an effort to persuade the Jewish Agency and the British and American governments to support Eichmann’s proposal, thereby sparing the lives of Hungarian Jewry.

Simply put, Brand failed. In retrospect it can be said that he was totally out of his league and did not comprehend what was happening. He was fanatically focused on saving Jewish lives --- certainly a goal that can absolutely not be dismissed --- but he did not understand the complications of military, political, and personal interests of others.

Grosz was a poor choice of travel mate. Although his company was forced upon Brand, it was a mistake to ever accept him. Grosz projected the image of a double agent. Was he working for the Gestapo or for the Jews? No one was really sure. Even Brand eventually explained that Grosz’s primary loyalty was to money. As it turned out later, Grosz was apparently carrying another proposal, purportedly from Heinrich Himmler.

The Jewish Agency rebuffed Brand, and Moshe Shertok (later Israel Prime Minister Moshe Sharett) did not meet with him. The author intimates that their efforts were directed towards the post-War era and establishing a Jewish state. The British feigned interest in the proposal, and when Brand traveled to Aleppo from where he was to enter Palestine, he was taken instead to Cairo and incarcerated. They could not make a unilateral deal with the Germans, and even if the Americans acquiesced, the Russians would oppose. The English would do nothing to cause the Russians to lessen pressure on the Eastern Front As time went on the Americans theoretically showed interest in the Eichmann proposal, but words were cheap and action was naught. Their soldiers were bogged down in France, and their advance was slower than anticipated. Providing trucks to the Germans would only be giving them military supplies to prolong the war. Eventually the proposal to save Hungarian Jewry became increasingly less relevant, as trains brought thousands --- hundreds of thousands --- of Hungarian Jews to the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

Why were the train tracks to Auschwitz not bombed? As is often claimed, that would certainly have slowed down the march of death (though not the sadistic random murders that the Nazis performed in Budapest). Florence cites the Casablanca Accord, in which the Allies agreed upon total victory with no negotiated settlement. He also reminds several times that General Eisenhower was totally dedicated to wiping out all military targets with no deviance to destroy railroad tracks to the death chambers. (Unfortunately the author fails to relate to bombings of civilian populations to weaken Nazi morale in places like Dresden.)

Ronald Florence tries to give an explanation of Brand’s personal failure. Was the Eichmann proposal serious? Or was it just a propaganda ploy to shift responsibility to the long list of countries which refused to accept Jewish refugees? Did Eichmann have the authority to make a serious offer? Florence is clear that Brand failed to convince others that there really was a chance to save Hungarian Jews. Even at the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, Brand’s testimony was unconvincing. The judges explained in their verdict that Eichmann’s offer was not serious. He did not have the authority and probably realized that nothing would come of it.

This book is fascinating reading and hard to put down. Was this a genuine offer to save Jewish lives? Let each reader decide for himself.

~~~~~~~

from the February 2011 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|