| |

January 2014 |

|

| Browse our

|

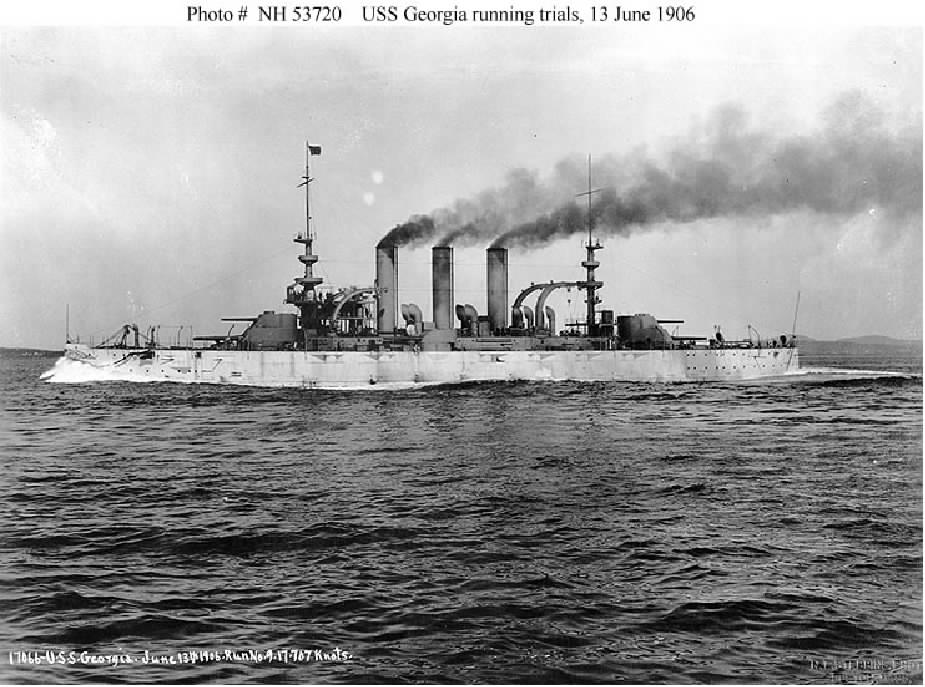

U.S.S. Georgia

The U.S.S.Georgia and The Mystery of Seaman Benjamin Kreiger By Jerry Klinger Benjamin Kreiger – "Hero" of the Georgia "The things you do for yourself are gone when you are gone, but the things you do for others remain as your legacy."

"Quick Wit and Bravery of Gun Loader Prevented a More Terrible Accident." The Scranton Truth, July 18, 1907

"The truth is rarely pure and never simple." Oscar Wilde

Captain Henry McCrea of the U.S.S. Georgia and Rear Admiral Charles M. Thomas stood stoically on the bridge with their field glass glued to their eyes. They watched with approving smiles as the just fired shell screamed through the air toward the distant gunnery target. The sound of the heavy booming thump from the 8" gun in the aft turret had not faded when the frightening cry went up to their ears "fire in the turret". Inside the turret something had gone terribly wrong. It was an instant. It was the longest minute. It was death pouring out smoke, fire and horror from every crevice of the aft turret… The gun crew of the aft turret was working frenetically, a mechanized machine of steel and muscle hoisting new powder to the just fired gun. The starboard (right) gun worked in an alternating synchronized dance with its sister 8" gun on the port (left) side in the turret, loading and firing, loading and firing, time and again, nine times so far in less than two minutes. The officers and crew wanted to show the Admiral they were the best. They were the fastest. There still was time to send another steel missile screaming down range at the bobbing distant target. They hurried. The breech on the right gun opened and a blast of flaming residue burst into the men behind the gun like a Roman candle flare. The flame, the gas, the heat singed the 52 lbs bag of smokeless powder being held by the loader. A second bag lay on the deck awaiting loading. A small black spot on the bag being held began smoldering, growing bigger. The powder bag cover was beginning to burn. The loader screamed to his fellows in the turret, fire, and dropped the bag. He knew what was going to happen. The loaders, the rammer, the gunner, the officers commanding the right gun, they knew what was going to happen. There was nothing they could do. A few feet away, across the deck, the turret's left gun was almost loaded. The second huge powder bag still protruded from the breech. The left gun rammer turned and looked up when he heard the scream. He saw a powder bag being held in the arms of his friend, William Thomas, the second loader of the right gun. A spot in the middle of the powder bag began to smolder an ugly, black red. Without waiting for orders, the rammer acted. He knew if the powder on the gun he was loading caught fire with the shell in the barrel, with the breech still open, it would be disastrous. The contained powder and shell in the gun would rupture, explode, destroy everything…them, the turret, extend to the powder and ammunition stores directly below the gun. The ship itself could be in danger. Not waiting for orders from the gun captain, he rammed the powder home and slammed shut the breech. Just as Benjamin Kreiger, the left gun rammer, slammed the breech of the left gun, the smoldering cotton cover of the powder being prepared on the right gun glowed very brightly. It flamed and exploded in a massive rain of fire, searing heat, a horrific concussion of blasting air confined inside the turret. Men had been diving for cover as best as they could when they heard the scream and saw the powder bag burning. They understood what was going to happen. They knew they were sealed inside a steel shell of death. The blast from the fiery explosion burned and tore off the flesh from the men nearest the gun. The glare, the smoke, the concussion, the screams were melted into an instant of terror. Burning powder rained everywhere and directly down toward the powder room. Boatswain Edwin Murray, in command of the powder room, directly to and below the turret through a vertical shaft, acted quickly. He looked up. Flaming grains of powder began raining down about him through the gaps about the automatic safety shutters…. He and his men raced to put out the falling fire before it could get to the fresh powder they had just brought out to the handling room from the stores. They cleared the powder bags away. Sealing the magazine and watertight doors, they prepared to flood the compartment knowing they might drown. They had to stop the fire from above from reaching the main powder magazine. The Georgia could explode. As quickly as Murray acted, he had been given a few more precious moments of time. Kreiger had prevented the explosion that would have ripped open the left gun. Murray would not have had even an instant of time to stop anything. Kreiger's immediate response bought a fraction of precious time. Instead of diving for safety and hiding from the coming right gun's powder blast, Kreiger had saved many of the men in the turret. The charges, the shell in the left gun, did not explode. In the fiery burning instant of a hell hotter than hell, Kreiger and nine other men, including three officers were horribly burned. Some died instantly, some died minutes and hours later from shock and tearing burns. Lt. Cruse lingered for a few days, clinging to a fading life until he succumbed. Kreiger had lied about his age to join the Navy just months earlier. He lied about his name. He had lied for two reasons. He was a Jewish kid, a runaway from his home and his family in Brooklyn. Giving the name, George E. Miller from Memphis, Tennessee, he figured it would make it harder for his parents to find him. Using the name, George E. Miller, would provide him with a certain degree of protection from the anti-Semitic taunts aboard ship that many Jews endured. The name George E. Miller did not provide him with any protection from the explosion in the turret. Hours after the explosion, in excruciating pain, mangled, burned beyond endurance, Benjamin Kreiger died. He was fifteen years old. ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ The official report of the naval investigation of the explosion within the aft – superimposed 8" gun turret on the U.S.S. Georgia, July 15, 1907, did not record the events quite the same way. Except to note that Ordinary Seaman Benjamin Kreiger (A.K.A. George E. Miller) died in the explosion, the Navy never acknowledged him. The National Press did. ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Riachuelo Contrary to popular assumptions the race for an American modernized steel Navy began not with the United States. It was a response to aggressive battleship construction by Brazil. Admiral Jose Rodrigues de Lima Duarte presented a report to the National legislature of Brazil on the importance of modernizing the Brazilian Navy (1880). The Brazilian government agreed. Brazil needed to project power through a strong navy that would protect Brazil's interests. Two steel battleships, the Riachuelo (1883) and the Aquidaban (1885) huge, modern, powerful ships bristling with the newest military technology were ordered from British shipyards. The addition of the powerful battleships to the Brazilian Navy along with the acquisition of other armored warships began a naval arms race between Brazil, Chile and Argentina. The American government was extremely alarmed. Brazil quickly had the most powerful Navy in the Western Hemisphere. At best the American Navy could only defend its ports against the new hemispheric threat. Congressman Hillary A Herbert, Chairman of the House Naval Affairs committee said, "if all this old navy of ours were drawn up in battle array in mid-ocean and confronted by the Riachuelo it is doubtful whether a single vessel bearing the American flag would get into port." The American frontier and the Western movement of American Manifest Destiny linking America from the Atlantic to the Pacific had not been completed. The American Civil War had barely been over fifteen years when the cold slap of international reality hit America square in the face. The American Navy was too weak to do anything about it.

U.S.S. Maine America responded by commissioning the construction of the first two American battleships, the U.S.S. Texas and the U.S.S. Maine. They joined the American fleet in 1895. Naval ship design and technology were changing so rapidly that the two new battleships were obsolete by the time they joined the service. The ships were the best America had.

U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor, January 25, 1898 Cuba had been a center of American expansionist interests even before the Civil War. Lying just 90 miles of the coast of the Florida, Keys, American involvement in internal Spanish affairs in Cuba had been a fact for many years. Cuban hatred and resentment of Spanish rule broke out into open revolt again in 1895, flaring aggressively by 1898. The U.S.S. Maine was sent to Havana Harbor to protect American interests.

The Maine in Havana Harbor after the explosion Tuesday evening, February 15, 1898, the Maine blew up in Havana Harbor. The explosion near the forward coal bunkers set off the ship's powder magazines just behind the coal bunkers. The forward third of the ship was destroyed almost instantly. 266 men, mostly sailors bunked in the forward compartments of the ship were killed. It is estimated that over ten per cent of the Maine's crew were American Jewish sailors. "The Spanish inquiry, conducted by Del Peral and De Salas, collected evidence from officers of Naval artillery, who had examined the remains of the Maine, Del Peral and De Salas identified the spontaneous combustion of the coal bunker, located adjacent to the munition stores in the Maine, as the likely cause of the explosion, however the possibility of other combustibles causing the explosion such as paint or drier products was not discounted. Additional observations included that:

The conclusions of the report were not reported at that time by the American press. "1

An American Naval court of inquiry, led by Admiral Sampson, into the sinking of the Maine, reached a different conclusion. The official conclusions of the court of inquiry issued to the Secretary of the U.S. Navy, March 21, 1898, emphatically came to the opposite conclusion of the Spanish report. The American report stated there were two explosions on the Maine. The keel was buckled upward indicating an explosion from outside the ship.

"In the opinion of the court, the Maine was destroyed by the explosion of a submarine mine, which caused the partial explosion of two or more of her forward magazines."

1911, the U.S. Navy returned to Havana Harbor to retrieve the remains of the sailors entombed in the wreckage of the ship. It provided another opportunity to investigate the cause of the explosion by the Vreeland Court of Inquiry. The Court's conclusion still blamed the sinking on an external explosion but they cast a shadow on the results of the Admiral Sampson inquiry and conclusions of 1898. The Vreeland report concluded that an external explosion caused the munitions stores to explode. The munitions on the Maine caused the keel of the ship to buckle inward.

Maine Memorial Arlington Cemetery

The dead were retrieved and buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Jew and Christian alike were buried in a common grave underneath the mast of the Maine. The refloated hull of the Maine was ceremoniously sunk at sea by the Navy a year later.

Seventy six years later (1974), Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, the "Father of the American Nuclear Navy", became intrigued by the question, what happened to the Maine? He concluded the Maine sank because of an internal explosion from within the ship that ignited the powder stores.

The National Geographic Magazine (1998) conducted a further examination of the sinking of the Maine with mixed results. They suggested that an external explosive device could have, but not 100% conclusively, have been the catalyst for the internal explosion.

The Communist Government of modern Cuba has a memorial to the U.S.S. Maine in Havana. The wording on the Communist monument has a very different point of view: "Victims sacrificed to the imperialist greed in its fervor to seize control of Cuba." From the Cuban view, U.S. agents deliberately blew up the Maine as a pretext for war with Spain.

The arguments continue with no official, definitive conclusion that satisfies everyone. Why the Maine sank remains controversial.

The destruction of the Maine became a catalyst for American Yellow, inflammatory and deliberately exacerbating, journalism pushed by media magnates William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer. The Spanish were guilty, period. "Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain".

America went to war.

The Spanish American War (1898) created a far flung American empire. Theodore Roosevelt became an American hero and icon as he led American troops in the famous charge up San Juan Hill. The first casualty of Roosevelt's charge was a sixteen year old Jewish boy from the Dakotas, Jacob Wilbursky.

America had joined the world race for Imperialist possessions. With an empire stretching from the Philippines in the Pacific, many thousands of miles from the Coast of California to the shores of Puerto Rice a few hundred miles from Florida, the United States needed a strong American fleet to protect the new American interests.

Theodore Roosevelt was an enigma, a politician and the quintessential American Western man.

His views on minorities and the continuing open immigration that brought millions to America's shores from 1880-1920 was pragmatic.

Four years before the Spanish-American war he wrote:

"We must Americanize in every way, in speech, in political ideas and principles, and in their way of looking at relations between church and state. We welcome the German and the Irishman who becomes an American. We have no use for the German or Irishman who remains such…He must revere only our flag, not only must come first, but no other flag should even come second."

President Roosevelt told Congress in 1905, "It is unwise to depart from the old American tradition and discriminate for or against any man who desires to come here and become a citizen, save on the ground of that man's fitness for citizenship… We cannot afford to consider whether he is Catholic, or Protestant, Jew or Gentile…. What we should desire to find out is the individual quality of the individual man."

Roosevelt was the first President to appoint a Jew to a Cabinet level position. Oscar Straus was already prominent in American political circles. He, following long established American traditions and anti-Semitic assumptions that Jews have an affinity, communication ability with Muslims that Christian do not, had been the U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire (Turkey). President Roosevelt appointed Straus Secretary of Commerce. The Straus family, well known as the developers of Macy's Department store in New York, along with Oscar, had two other brothers. Isidor Straus would gain posthumous immortality when he and his wife perished on the Titanic. Nathan Straus is less well known. However, he is probably of greater significance to the American and Jewish experience than his brothers. Nathan forced New York, while demonstrating to the world; pasteurized milk could save children's lives. He and his wife are estimated to have saved 600,000 children from disease laden milk and death. He is also famous for his intimate, key relationship with Louis Brandeis and their mutual ardent support for Zionism. It was Nathan Straus who first made Louis Brandeis aware of Rev. William Blackstone and the Blackstone Memorial (1892) calling for a Jewish return to their ancient homeland. Brandeis used Straus as the intermediary to have Rev. Blackstone intercede on behalf of Zionism and influence President Wilson to support the Balfour Declaration leading to the creation of the modern state of Israel. Theodore Roosevelt had been the U.S. Secretary of the Navy for a short stint prior to the Spanish-American war. He believed fervently in the necessity for a strong Navy to protect and represent American interests. Always the consummate politician, Roosevelt used his fame from the War to get himself elected Governor of New York. Two years later, in 1900, partly to get rid of Roosevelt and his reformist policies, Republican political leaders forced Roosevelt onto William McKinley's second term Presidential ticket as the Vice-Presidential candidate. McKinley had been President during the Spanish-American war. To the horror of the country, McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist, Leon Czolgosz, as he stood in a greeting line for the American public at the Pan-American exposition in Buffalo, New York. Czolgosz believed that American society was unjust. There was inequality that allowed the rich to exploit the poor. He was deeply influenced by American anarchists such as Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. Czolgosz believed he could remedy, or certainly bring attention to, the injustice in American society by shooting McKinley. September 14, 1901, Theodore Roosevelt became President of the United States. He suddenly was empowered to imprint his vision of American influence, American power and American worth. The United States Navy had handily destroyed the Spanish Navy in the recent war. Yet the United States Navy was considered and remained far less than a third rate world power. Roosevelt had every intention of changing that. He embarked upon a major upgrading of American Naval power. The U.S.S. Georgia's keel was laid down at the Bath, Maine Iron works, 1901. She was the biggest, the most powerful, and the most modern of the new Virginia Class of Battleships being produced by American industry and Naval Military technology. The Georgia was best fighting ship that America could produce. She was commissioned September 24, 1906. Fitting her out took another number of months. After a brief shakedown cruise she joined the Atlantic Fleet as flagship of the Second Division Squadron 1, promptly departing for Guantanamo Bay March 26, 1907. As part of a planned public relations campaign of the U.S. Navy and the Government, the Georgia joined other elements of the North Atlantic fleet at the Jamestown Exposition, June 10-11, 1907. President Roosevelt reviewed the fleet from his Presidential yacht. June 15, 1907, the Georgia, along with the Battleships of the Atlantic fleet, was off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts for gunnery practice. A further shakedown cruise for the entire fleet was ordered to hone battle effectiveness. Three Naval Admirals alone had been advised what President Roosevelt actually had in mind for the exercises. Not even President Roosevelt's cabinet knew Roosevelt's plan. Roosevelt had grown the U.S. Navy until it was ranked the second most powerful Navy in the world after Great Britain. It was a debatable distinction. Two years earlier, 1904-5, the Japanese Navy had decimated the entire fleet of the powerful Russian Navy in the brief Russo-Japanese war. President Roosevelt negotiated the peace treaty between Russia and Japan in Portsmouth, Maine. He received the Noble Peace Prize for his efforts. Peace was declared but peace was not a gentle lady. The Japanese were confident in their newly, factually demonstrated, naval might. They began flexing their military muscle in the Pacific trying to extend their political zones of influence. Roosevelt well understood what that meant. It meant Japanese threats to America's recently won colonial empire in the Philippines, Guam and even a threat to the Hawaiian Islands much closer to American shores. It was a threat he could not let go quietly.

The Great White Fleet - 1907 Roosevelt needed to project American power not just in the Atlantic but in the Pacific as well. He needed to show the Japanese that America was prepared to defend its interest in the West. America was capable of fighting a two ocean war. Roosevelt planned to assemble his newly built powerful fleet, the hulls of the 16 battleships painted white for effect, and send them on a cruise around the world. Roosevelt was going to use the American navy to project American power, American industrial might, American military excellence and naval design technology around the world. He secretly ordered the American fleet not just to practice gunnery off the coast of Cape Cod but to work out the kinks in the ships for the around the world cruise of American battle power. The Great White Fleet, as it became known, sailed December 16, 1907. It was reported that President Roosevelt threatened to court martial anyone criticizing the mission. The Great White Fleet, its mission and the projection of American influence were incredibly successful. Roosevelt was right.

The reception of the Great White Fleet in Auckland, New Zealand July 15, 1907, Admiral Thomas stood on the bridge of the U.S.S. Georgia next to Captain Henry McCrea. McCrea had taken command of the Georgia the day before. They stood together approvingly observing the high speed and accuracy of the Georgia's guns in timed target practice. Their field glasses were glued to their faces as another round from the aft super imposed turret's 8" gun boomed. A shell screamed across the sky toward the distant target. They smiled. Suddenly, the cry rang out – "fire in the turret". The commander's smiles turned to gut cold firmness as they raced to see what was happening from the bridge's aft vantage point. Fire, smoke and clearly death belched from every orifice of the 8" superimposed turret. Men scrambled about the outside of the turret, hauling hoses, dousing the fires, playing water in every direction. The turret opened, men struggled to get out. Some were blinded. Some had flesh hanging from their bones like frighteningly over-cooked meat. Other burned men staggered out. Some jumped into the ocean to extinguish the powder fires still burning in their flesh. Rescue crews fought their way into the horror of the turret. The guns were fine. The men… ten men including the rammer-man, Ordinary Seaman George E. Miller as he was known to the navy on the enlistment records, would die painfully. Some had died immediately in the fiery blaze and were no longer recognizable. Some died as the ship ran at full speed for Boston Harbor trying to get to the Chelsea Naval Hospital with the survivors. Some died days later, their suffering unabated by medical science, ended only by death. Eleven men were wounded. Seven men survived. The Navy did not know what happened. The accident occurred at 10 A.M. An hour and a half later, Admiral Charles M. Thomas, Commander Second Division, First Squadron, U.S. Atlantic Fleet ordered an investigation. The public was very hungry for information about the tragedy. Differences between what was told to the newspapers by the Navy and what was leaked unofficially are considerable. "U.S.S. Georgia2

Target Grounds, Cape Cod Bay, Mass.

11:30 a.m. Monday, July 15, 1907.

The Board met pursuant to the above mentioned order.

Present:

Captain Seaton Schroeder, U.S. Navy, Senior Member

Captain W.W. Kimball, U.S. Navy, Member

Lieutenant-Commander M.I. Bristol, U.S. Navy, Member

Lieutenant K.G. Castleman, U.S. Navy Recorder

The order convening the Board was read, hereto appended marked "A", and the Board decided upon the course of its procedure.

The Board proceeded to the after eight-inch superposed turret, and, upon examination, found the following conditions to exist:

The left gun was loaded. The right gun was slightly depressed, breech open, loading scoop in place, gas ejection cut off, ammunition car all the way up, the shell still in the car with the shell tray in the up position, both sections of the charge removed. The rammer was all the way back in the withdrawn position and the controller pointers indicated current off both the rammer and hoist motors. The paint in rear of the right car immediately under the eight-inch turret floor was charred; no sign of charring or injury of paint in front of the car. The rear edges of the rivet heads in the middle part of the framing of the roof leading toward the training hood were discolored as if by burning, also the inner edges of sight holes of that hood. The charred remains of a seaman's hat were found jammed under the base of the ogvial of the shell in the care car. A chief petty officer's cap was found uninjured in the training hood. From the charred appearance of the paint work, it seemed that the hottest part of the fire had been just inboard of the right rammer in the second loader's position.

A further and more detailed examination was, at the time prevented by the departure of the Georgia under orders to proceed to Boston, to transfer the injured to the Naval Hospital and return to the Target Grounds. The board therefore, at 12:15 p.m., adjourned until 9:00 a.m., tomorrow the 16th instant."

July 16, Board Investigation, 9:00 AM:

The hearing began with Captain McCrea, the Captain of the Georgia testifying. The Board began by questioning the Captain about the direction of the wind and the direction that the smoke from the smokestack was blowing. It was to be the only line of questioning of the Captain that the Board pursued with him. McCrea had the great misfortune to take command of the Georgia the day before. He could only testify on what he observed during the gunnery training.

Knowing the direction and strength of the winds was very important to the Board. Coal powered ships were infamous for belching not just smoke from the smokestacks but also blazing embers of not fully combusted bits of coal. The dangerous fiery embers could blow back into the muzzles of the guns as they were being loaded with fresh shells and powder causing explosions.

Captain McCrea responded – "It was a little on the port bow, not much wind, except what we made with speed."

A few more questions along the same line and the Board released Captain McCrea from further testimony.

He was followed by the ship's surgeon, testimonies, and reports of the officers and enlisted men that would serve as addendums to the Board's report after the individuals were interviewed. Chaplain Charles N. Charlton reported the death bed testimony of Seaman Pair, the first loader on the right gun.

Testimony over the next three days would be technical. Was the accident caused by mechanical, operational or human failure?

Of all the men who testified only Midshipman Kimball, Gunner's Mate First Class Charles Hansell, Seaman Rosenberger and Seaman Eich had been inside the turret.

Midshipman Kimball, the only surviving officer from within the turret testified. He was about to give instructions on the left gun when a commotion caused him to turn around and see burning powder on the floor behind the right gun. He covered his face with his hat and dove under the left gun followed by Gunner's Mate Hansell and Yeoman Tagland. Kimball testified that at the time of the explosion "the left gun was nearly ready for firing." The breech was closed.

Benjamin Kreiger was the rammer on the left gun. He was positioned behind Kimball. When Kimball turned to see the burning powder on the floor of the right gun he most likely would not have been able to see Kreiger.

The Board tested the equipment and the electrical systems for possible malfunctions. They found none.

Lt. Upham was called to testify. Upham observed the unloading of the left gun. "At the time of the accident this left gun was loaded. When the powder charges were withdrawn from that gun the rear end of that section next to the mushroom showed three brown smirches which might have been scorches or more probably were marks from the mushroom itself, as dirt from previous firings of the gun."

Could the rear powder bag in the left gun have been exposed to possible scorching? The answer was left open to conjecture. The question was important if in fact Kreiger had shoved the powder in and closed the breech. The answer was inconclusive.

Syndicated newspapers across the United States blared out the news of the Georgia disaster to a shocked public. The accident on the Georgia was a major operational and public relations disaster for the Navy and President Roosevelt.

The Washington Post, July 16, 1907

"Blast Kills Eight on Battle Ship Georgia: Thirteen others Injured by Powder igniting during Target Practice. Lieut. Casper Goodrich Dead – Maddened by Pain He Leaped Into the Sea, but Was Taken on Board to Die in Agony. Cause of Accident Not Established."

"Tragedy shocks Navy: News Sends Thrill of Horror Through Department – Explosion Not Understood:

"Experts unable to understand how elaborate orders given and precautions taken failed to assure safety. Four other accidents within four years – Board to investigate."

"Ordered Back to Sea

While the ship was at the pier a few of the officers including Captain McCrea came down the gangplank for a brief conversation with officers attached to the navy yard and the war ships at present in port. None of them would discuss the incident."

Indiana Evening News, July 16, 1907

Sailors perish in Powder Flame

"…Explosion Shake Confidence

Aside from their deep concern over injuries suffered by the unfortunate turret crew of the Georgia, the officials of the Navy Department were a good deal cast down when they heard of the accident, as it tended to shake the confidence in which they have rested for more than a year in the perfection of the regulations so carefully framed with a view to safeguarding human life within the turrets….

The Washington Times, July 16, 1907

"Alarming Record of Disasters on American Warships….Four times within four years have catastrophes mown down the men whose daily duty carried them to and fro near the big guns of the ships of the United States Navy.

After each catastrophe the department thought all precautions possible had been taken to prevent further loss of life. That belief has been effectively shattered by the deaths on the Georgia yesterday."

The next day the Washington Post reported on the Georgia tragedy. It listed the accidents and the number of casualties.

"January 18, 1903- Charge of powder in the 8" gun exploded on the Massachussets, killing nine enlisted men.

April 9, 1903 – 12" gun on the Iowa exploded during target practice. Killing three enlisted men and wounding four others.

April 13, 1904 – A terrible accident occurred on the Missouri when by a 'flare-back' an explosion was caused which resulted in the death of five officers and twenty-six enlisted men.

April 13, 1905 – An explosion in one of the 6" turrets of the Kearsarge, severely wounded three men. "

The Board reconvened, Wednesday, July 17.

Lt. Wygant testified. Wygant and Lt. Davis had carried the badly injured Lt. Goodrich to his bunk. Goodrich was in command of the turret. Goodrich managed to tell them, "Jeff, that bore was clear."

Lt. Caspar Goodrich was the officer in charge of the turret. It was his responsibility to be sure that after the gun was fired there were no residual gases or burning materials that could flare back into the turret and cause an explosion. Lt. Goodrich was the son of Rear-Admiral Goodrich, the Commandant of the New York Navy Yard. In World War II, a ship was named in honor of father and son.

The Board proceeded to interview survivors at the hospital. Only three were well enough to testify – Eich, left hoistman, Hansell, gun captain left gun and Rosenberger, first loader left gun.

Seaman Eich – hoist man on the left gun. He stated that the left gun was loaded and he looked over to see that there was burning powder on the deck. He finished lowering the ammunition car on the left gun and hit the deck. He did not mention Kreiger who was standing five feet from him.

Gunner's Mate First Class - Charles Hansell:

"I was stationed at the left gun as gun captain. In my left hand, I had the ready signal and, in my right hand, the firing signal of the left eight-inch gun. The gun had just been loaded and I had given the ready signal. As soon as the head of the rammer (Kreiger) had cleared the breech of the gun, it was, to my knowledge, about one half a turn around on the block and I heard a noise. I took my eyes off of the breech terminals and looked across to the right gun and saw the second loader standing with a section of the charge in his arms, facing about one quarter of my way, and I saw in the middle of the bag and about on the side a black speck a little larger than my hand, the next instant I saw the flame. It went off with a puff. I covered my face with my arms and backed away from it up against some men who were standing on the left side of the left gun and they were crowing one another and I felt the head on my back and I turned directly around and went underneath the gun and underneath the gun I met Midshipman Kimball and went as far frontward as I could and got up against the gun port. The second puff must have went off as I was getting underneath the gun…"

A Board member asked Hansell an unusual question.

Q. Have you ever been stationed in a turret at target practice before the preliminary and record target practices of the Georgia on this occasion.

Hansell answered, "No, Sir."

Hansell was completely inexperienced as a turret gun captain. Kreiger was standing in his line of sight, between him and the burning powder. Kreiger was never mentioned.

Seaman S.L. Rosenberger, the first loader on the left gun testified. He was "shoving" in the second bag of powder into the left gun when he saw the smoke coming out of the right gun and flames going up from the deck. He did not confirm if the powder bag had been fully inserted into the breech. He testified that the plugman, Thomas, had closed the breech when the smoke started.

When he saw the flames, Rosenberger hit the deck. Kreiger would have been standing in his line of sight. He never mentioned Kreiger.

Technical testimony was taken about flare backs and their causes. A flare back occurs if the barrel of the just fired gun has not been properly cleared and the breech is opened too soon. A searing blast of hot gases and possibly burning material is shot back into the turret. Premature opening of the breech and premature preparations of gun powder is a major safety risk.

It was determined that the gas ejector on the right gun, designed to prevent flare backs, was working properly.

Testimony was finished for the 17th.

July 18 – Board reconvened.

Chaplain Charles N. Charlton testified he had spoken with a badly burned Seaman Pair in the sick bay. He spoke with him about ½ hour after the explosion.

"I said to Pair, 'Pair, what was you doing when the accident happened? His answer, 'first loader, looking into breech.' 'Tell me what happened?' 'Flame came out of my gun and struck me.' 'Are you sure?' 'I think it did; not sure.' 'What gun was you working on?' 'Working on the right gun."

Midshipman Brown went over the proper procedures for operating the 8" gun.

Seaman W.C. Symth testified about his visit with Pair. Pair said "something dropped over his head, there was a big flash, something hurt his eyes and he could not see anything more after that. He heard the men groan and he did not know what had happened at all. "

What Pair saw and experienced was consistent with a flare-back. Pair died before the Georgia reached Charleston Naval Hospital.

The Board would reconvene on the 19th.

By the evening of the 18th, rumors and speculation about the accident flew through the media. The Navy had provided some information, even schematics of the superimposed turret. Some news reports thought the explosion might have been caused by sparking from equipment inside the turret. Others thought the powder was defective. Perhaps it was spontaneous combustion of gases a few wrote authoritatively. Still others suggested it could have been a flare back or worse, mismanagement within the turret by the Officers.

San Antonio Gazette, July 18, 1907

"Rapid Firing Caused Disaster on the Georgia

By Scripps Press

Boston, July 18 – At the conclusion of the investigation into the disaster aboard the battleship Georgia today, it was authoritatively reported that the finding the board of inquiry is that the explosion in the gun turret was caused by the spontaneous combustion of gases generated by extreme rapid firing. The report of the board was forwarded to Washington this morning.

The investigation was carried on with great secrecy and every effort made to conceal the finding of the board appointed by rear admiral Charles H. Thomas. No new deaths among the inured have been reported and the list of dead now contains nine names.

After making a thorough inspection of the turret where the explosion occurred and taking the evidence of the men aboard the ship, the officers went to the United States naval hospital at Chelsea and questioned the wounded men. Many of the inured are horribly burned and more deaths are expected.

The officers of the fleet reject the theory that the powder was ignited by sparks form the funnel. It was known that the gun crew in the turret was ambitious to become the crack crew of the fleet and it is thought that in their zeal they disregarded proper precautions.

It was learned today that the dead seaman known as George Miller had enlisted under an assumed name. His real name was Benjamin Kreiger, and his former home was in Brooklyn."

The Scranton Truth – July 18, 1907

"Quick Wit and Bravery of Gun Loader Prevented A More Terrible Accident.

Boston, July 18 – The report of the board of inquiry which is investigating the disaster on board the battleship Georgia will probably be forwarded to Washington today. From unofficial but trustworthy sources, it is learned today that several members of the board expressed an opinion that the accident was due not to a spark, but to spontaneous combustion of gases generated by extreme rapid firing.

The crew in the upper turret were straining every nerve to break the record for quick work and the close interior of the steel box was filled with highly inflammable vapors generated by the discharge of the big gun.

This explanation has practically been forced upon the board as minute search has failed to discover any evidence in support of the spark theory…

The Georgia remained here over night so that its crew might pay the last honors to Benjamin Kreiger, whose body is the only one which has not been claimed by relatives. Krieger appeared on the list of dead as 'George Miller," the name under which he enlisted…

(Kreiger was buried in the Chelsea Naval Hospital cemetery under Episcopal rites. An honor guard accompanied the body but did not fire a volley of final salute.)

…Captain McCrea declares that the bravest deed of all was performed by the gun loader, who when the powder first took fire, instead of rushing to a place of safety, shoved home the bag of powder already part way in the gun and closed the breech, thus preventing an explosion which would have killed every man in the turret and perhaps wrecked the ship.

'That's the kind of stuff in the American man-of-war or warsman," said Captain McCrea…"

Board of Inquiry – July 19

The Board came to a series of conclusions about the causes of the accident. The most important were:

"b) All the rules and regulations prescribed for carrying out target practices were being observed during the firing of this turret, also all prescribed safety precautions except it appears that after the firing of the right gun immediately preceding the accident the air blast was shut off and the ammunition car consequently brought above the turret floor before the bore was cleared of dangerous gases. At the time of the accident the turret was under the charge of the late Lieutenant Caspar Goodrich

i) Those in the turret were made cognizant of the danger by some startling occurrence which immediately preceded the burning of the two sections which ignited with two separate bursts of flame.

J) The ammunition car of the right gun was brought above the turret floor and to the loading position before the bore of the gun was cleared of dangerous gases.

The Board found that the crew of the right gun had pushed the limits of operational safety in the interest of achieving greater firing speeds. The air ejector on the right gun had been turned off too soon after firing of the gun. It was probable that dangerous unburnt; gases and debris had been left inside the gun when the breech was opened. The debris and gases contributed to a flare back and the resultant explosion.

Addendum Statements to the official report were included:

Captain McCrea

"There were several instances of individual bravery; and none that I learned of, that were other than gallant."

McCrea never mentions any names.

Lt. Wurtsbaugh

Special commendation to Midshipman Kimball, Boatswain Murphy in charge of the powder rooms below, Seaman Tagland, Hansell and Sclapp.

Kreiger is not mentioned.

Midshipman Kimball

Special commendation to Murphy, Tagland, Hansell and Sclapp. He repeated that the breech on the left gun was closed. The final official report said it was partly closed.

Kreiger is not mentioned.

In the official report to the Navy Department about the explosion on the Georgia, July 15, 1907, George Miller is only mentioned once as a casualty. Benjamin Kreiger is not mentioned at all though the Navy knew his real name by the time the report was issued.

The evening of the 19th, the Board completed its investigation. It remained only to be officially typed up, reviewed and submitted. American newspapers carried in detail the funeral of Lt. Goodrich. The funerals for the enlisted men who died were hardly mentioned by the news reports except for the funeral of George Miller (Benjamin Kreiger) in the Chelsea Naval Hospital cemetery.

Papers nationwide carried stories about Benjamin Kreiger and the mystery of who he was.

The Washington Post, July 19, 1907

"Naval Hero Identified – Seaman who Gave Life for others on Georgia was Brooklyn Boy

Special to the Washington Post:

New York, July 18 – Identified as Benjamin Kreiger of Brooklyn. "George Miller of Memphis, ordinary seaman, no home, no kin," as he is officially recorded, has been found to be the real hero of the explosion in the turret of the battle ship Georgia. He died as the result of his bravery.

Seaman Miller, or Kreiger, was eighteen years old, and ran away from his home last February and enlisted at the Navy Yard in Brooklyn, giving his name as George Miller, of Memphis, and stating that he had no home and no living relatives.

To some of his shipmates he confided that his parents were alive and the he had written to his father in Brooklyn but had received no reply.

The Navy Department will make an effort to locate the family of the dead hero. Meantime the body of 'Seaman Miller' will be interred with naval honors at Boston and should the relatives appear they will have the privilege of disinterring the body."

San Francisco Chronicle, July 19, 1907

"Disaster Due to Spark in the Gun

Hero of the Georgia, A Jewish Boy – Belief that Miller, Who lost his life in the Turret, Was from Brooklyn.

New York, July 18, Vain search so far has been that for friends, home and even the real name of a nineteen year old sailor who called himself George Miller and who died aboard the battleship Georgia after having performed in the moment of the turret explosion a most plucky, quick witted and devoted act. Some of his shipmates believe he was Benjamin Kreiger, formerly of Brooklyn with a father in Los Angeles.

He shipped in February, giving the name of George Miller and Nashville his home and George Charles of 95 Seigle Street, Brooklyn as his nearest friend. No George Charles could be found there or elsewhere in Brooklyn today. Inquiry in the Seigle Street neighborhood disclosed that several young Yiddish boys had shipped there into the Navy. The neighbors thought Miller might have been one of these boys. He would have changed his name upon enlisting to avoid being teased by his shipmates because of his Jewish name. It was said at the recruiting office that many Yiddish boys enlisted and hid under assumed names."

The Scranton Truth, July 20, 1907

"Although it was announced by Captain McCrea that the name of the young hero of the Georgia, who sacrificed his life in saving others, was unknown, it turns out that he was Benjamin Krieger and that his parents are living in Brooklyn. Kreiger, who was only 18 years old, ran away from home last February and enlisted at the navy Yard under the name of 'George Miller'."

The mystery of George Miller (Benjamin Kreiger) and the utter lack of proper memorialization rose to the level of scandal.

The Des Moines Daily News, July 22, 1907

"A Grave and a Wreath For American Hero Who Died to Save Half Hundred Comrades – what shall be the monument of George Miller, who remained at his post in the turret of the Georgia, though death was at his throat?

…The unclaimed body of the American seaman has been laid to rest in the little cemetery attached to the naval hospital at Chelsea.

A wreath of wild roses is his only monument.

What shall be the lasting monument of this real American hero? Will it be of granite or will it be the memory and example of his exalted deed?

And who among us shall write his epitaph, we who knew that he gave his life to save a half hundred comrades who escaped: we who know that instead of looking to himself he pushed a powder charge into the breech of an eight –inch gun and thus placed it out of harm's way. Had it become ignited there would have been a terrific explosion, the powder being confined, and every man in the turret would have been a corpse in a second.

Comrades are telling the story over and over with wet eyes, that when Miller performed this feat the turret was swept by a perfect hell of fire and gases from the bag of powder accidentally ignited. Men were struggling to climb a ladder that promised safety, and others were dropping to the floor to escape the blast of fire and suffocating fumes. True to the highest ideals of courage Miller held to his post. His was the self-sacrifice of the 'man behind the gun.'…

Capt. McCrea of the Georgia, has paid tribute to the heroism of Miller. His formal statement says that but for the act of this youth not a man in the turret would have been left alive, whatever other damage might have been done.

'That man,' he says, 'gave his life for others.' The Captain adds."

Not all the press was adulatory. For reasons unknown, pieces of the Board's report taken out of complete context had been leaked to discredit Kreiger.

The Daily Free Press (Carbondale, Illinois), July 26, 1907

"Seaman Miller not Hero

Naval officer testifies that he found breech of gun open after tragedy.

Benjamin Kreiger, known as ordinary Seaman George Miller, was not the hero of the explosion of the battleship Georgia, and he did not close the breech of the port gun and thus save the lives of many members of the crew, according to the report which reached the navy department Thursday.

An officer who appeared before the board did testify he found the breech of the gun open after the explosion.

The Daily Free Press article was a deliberate misrepresentation of the conclusion of the Board that found the breech partially closed. Testimony at the hearing by Midshipman Kimball and others repeatedly stated that the breech was closed. The Daily Free Press may have had its own reasons for running the story.

News reports discrediting Kreiger remained sparse and unreported.

Kreiger's family was located in San Francisco. His family wished to have his remains brought for burial in a Jewish cemetery near them. The Navy made the arrangements and turned the remains over to the Kreigers.

San Francisco Chronicle, August 7, 1907

"Body of Hero Reaches Home – Victim of Georgia Explosion will be borne to grave with honors.

The body of Benjamin Kreiger, the boy hero of the powder explosion aboard the battle-ship Georgia during target practice off Cape Cod, July 15th, reached San Francisco Tuesday morning, and will be buried with military honors from Halsted's Chapel, 924 Fillmore Street, Thursday morning.

Kreiger was a San Francisco boy, the son of Nathan Kreiger a poor refugee at the Richmond camp…

When the news of the tragedy came to San Francisco where the Kriegers had been living for nine months, a reporter from the Chronicle (San Francisco Chronicle) interviewed the grief-stricken family. The mother of the young hero 'became prostrated and… in a state of collapse.' The father was described as one who 'does not speak much English, the bright little (son) Jacob acting as interpreter' explained that the family wanted the body brought to San Francisco for burial."

The San Francisco Chronicle openly ran the headline, Hero of the Georgia, A Jewish Boy, July 19. The leading papers of the country, the New York Times, the San Francisco Examiner, the Los Angeles Times, declined to identify Kreiger as Jewish.

Rabbi Jacob Voorsanger of San Francisco's Congregation Emanu-El gave the funeral address

The Jewish community's concern for the Kreiger family did not end with the funeral.

San Francisco Chronicle, August 27, 1907

"Mother of Navy Hero Killed On Battleship Will Receive Pension – Interests President.

Rabbi Kaplan Forwards Him Letter and Notice Is the Result.

Mrs. Kreiger, mother of Benjamin Kreiger, the sailor killed in the explosion on the United States battleship Georgia, is to receive a pension. This was brought about by the efforts of Rabbi Bernard M. Kaplan, who took an interest in the parents of the boy, who are in poor circumstances. He wrote a letter to President Roosevelt, stating the circumstances and the announcement of the grant was the result.

(On behalf of the President, Acting Commissioner J.L. Davenport responded.)

"With reference to the inquiry you make, as to a medal which you think the sailor would have been entitled to had he lived. I am unable to give you any information."4,5

No medal or citation was ever added to the Navy's records re: George E. Miller (Benjamin Kreiger)

Two years later the Jewish community decided that Kreiger deserved more than a simple obscure grave. The question the Des Moines, Iowa newspaper asked how was George Miller to be remembered? was being answered. The Navy detailed a large honor guard of thirty men.

San Francisco Chronicle, July 2, 1909

"Monument To Naval Hero To Be Dedicated Sunday

Appropriate Service in Memory of Benjamin Kreiger Will Be Held.

The monument to the memory of Benjamin Kreiger, the young San Franciscan who perished at his post in an explosion on the battle-ship Georgia on July 15, 1907, will be dedicated next Sunday afternoon at the Eternal Hoe Cemetery. Rabbi Kaplan will officiate at the ceremony, which will begin at 2:30 o'clock.

A detail of thirty men from the Mare Island Navy Yard will participate in the services, which will be simple in character and of an appropriate nature. The monument, which is of a beautiful design, is the gift of friends of the Kreiger family."

The final report on the explosion in the aft superimposed 8" gun turret on the U.S.S. Georgia never mentioned Benjamin Kreiger. An unknown shipmate of Kreiger's told the Navy his real name before the Board's report was finalized. The Navy acknowledged Miller as Kreiger after his burial, disinterring his body and turning the remains over to his family. A month later, his mother was granted a pension from the Navy based upon Kreiger's service. President Roosevelt had interceded on her behalf. Kreiger had never sent his family any funds or provided support to them, a requirement of the pension law.

No records have been located yet confirming Captain McCrea's statements, officially or unofficially, that Benjamin Kreiger was the hero of the Georgia.

How the press came up with the name and the role of Benjamin Kreiger, an obscure rammer on the Georgia killed in the tragedy, is unknown. Shipmates knew his real name. Perhaps they also knew more. It is an incredible stretch to believe that the press invented the Kreiger story, for what purpose?

Inconsistencies with the Navy's official investigation of the explosion remain difficult. Why the Board was in a hurry to find a quick, probably politically correct conclusion to the cause of the accident without examining what happened to all the men in the turret is unclear. Anti-Semitism was a fact in the U.S. Navy in 1907. There is no official evidence it was a factor in the Navy's response to Benjamin Kreiger.

The U.S.S. Georgia and the Mystery of Seaman Benjamin Kreiger needs to be investigated much further.

Conjecture is not fact.

Rear Admiral Charles M. Thomas became Commander in Chief of the Great White Fleet, May 9, 1908. He replaced Admiral Evans who left for health reasons. Five days later, in San Francisco, May 14, 1908, Thomas retired from active service and command. He died July 3, 1908.

Captain Henry McCrea was relieved of his command in San Francisco in 1908. He died on the way to a new posting in Washington, D.C., July 20, 1908. He suffered from Bright's Disease. Captain McCrea's only child, his son, died of heart failure on a Pullman to Pittsburgh, July 28, 1908.

The U.S.S. Georgia (BB-15) was sold for scrap metal, November 1, 1923. Her name was stricken from the Naval Vessel Registry, November 10, 1923.

No matter how the final story is colored or if what really happened with Kreiger on the Georgia is ever known, Benjamin Kreiger gave his life for his country. Benjamin Kreiger is an American hero.

Jerry Klinger is President of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation,

2

Official transcript records from the United States Archives, Washington, D.C. 3

Western States Jewish Historical Quarterly, July, 1982, by Norton B. Stern and William M. Kramer.

4

Ibid. 5

An inquiry is being made by the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation re: any posthumous recognition was not given.

from the January 2014 Edition of the Jewish Magazine Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used. |

|

| All opinions expressed in all Jewish Magazine articles are those of the authors. The author accepts responsible for all copyright infrigments. |