|

I Feel Guilty

By George Liebermann

After so many years, sixty to be precise, my uncle Louis still bothers my conscience. I met him when I was six, he only returned from Milan where he studied to be a watch maker. He was bold, and I asked him if he also had face on the top of his head. Shortly thereafter he married Irene, and I lost him from sight.

Ten years went by. A ghetto had been built in Nagyvarad, but we haven’t met. We did not meet in Auschwitz, but we did in the camp of Thil, in northern France.

In Thil we made parts for V1 rockets. Since we worked in different Shifts, I only met Uncle Louis on a Sunday at the lavatory where I washed my aluminum plate. Uncle Louis did not finish his lager-soup yet, said that he was not hungry and offered it to me. I knew that he lied in order that I should eat his meal but I was not hungry enough to take it from him.

Next day we found out that the Allies landed in Normandie, I don’t know by what miracle, but the Organisation Todt delivered us a few barrels of beer. We got tipsy and began to sing, oddly enough in refrain with the German soldiers, something like:

“Alles gehts über.

Alles gehts vorbei,

Und Hitler und Himmler

With Ihre Partei.”

Meaning: “Everything comes to an end, even Hitler and Himmler with their party.”

After a few weeks, the Allies got closer. One night we woke up to a fire. It was the SS men who were burning their documents.

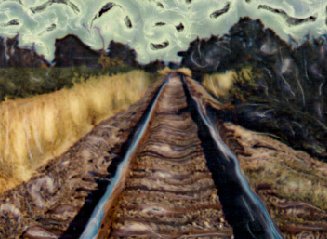

Then we were taken by train, in open box cars, through Luxembourg into Germany. It rained cats and dogs, we were soaking wet, but by some miracle, none of the five hundred of us caught a cold.

At midnight we reached the first border town inside Germany, Koblenz. It rained all the way. We saw the road that ran parallel with the railroad. An endless line of German refugees headed towards East, afoot, on bicycles, pulling two wheeled carts loaded with chairs, tables, bedding and babies. The sight warmed our hearts: the Krauts were running.

We even saw a dogfight that took place right above our heads between U.S. and German fighter planes.

The next ext day we arrived to Kochendorf, a huge camp loaded with Russian prisoners.

A salt mine waited for us. One hundred seventy meters down below, was the mine proper. A big iron elevator took us down. Everything shined. Straight ahead the terrain looked like a soccer field. Some decoration looked like a church, but everything had been distorted, the cross, Jesus, the altar. The Nazis disliked religion related items and wanted no guilt that would restrain them from commiting their mass murders.

I saw men eat salt - better to say lick it. It seemed that one had to die one way or another. I wasn’t ready yet. As soon as we marched back into the camp, I bumped into Pierre the miner from Luxembourg whom I previously befriended in earlier encounter. He stopped me. When I told him about the mine, he said, “No more. I will find a spot in the kitchen for you, as Kartoffenscheller.”

He always kept his promises. My French friend was Dr. Mourbeillet, the Rewier physician. The secret of our survival was snails.

Back in Thil, on the way from the city to the camp, four kilometers, I collected snails, took them to the doctor and he cooked himself escargot. He gave me a tablespoon of cod liver oil each day from then on. It helped that I was fluent in French.

Our “friendship” lasted all the way to Kochendorf. One day he came up to the idea to declare me “sick”, hospitalized me, then made me the chef of a transport of eighty sick fellow prisoners. He called me “Dolmetscher” (interpreteur).

I tried to talk my uncle Louis into joining us, but when he heard of Dachau, he declined. He said, “Dachau is another Auschwitz. Dr. Mourbeillet reassured me that after an inspection by the Swiss Red Cross, the gas chambers had been demolished. My uncle did not believe me. I also had some doubts but I was willing to take the chance.

“Nicht da gewesen,” ”it never happened before.” We traveled comfortably, twenty in a box car, sat on benches. The train stopped somewhere, but I could not recall the name of the place. It was hard to believe that Red Cross nurses brought us coffee and they cried.

We arrived to Dachau at night. We were taken by truck to the camp and into a round building with windows. In the middle there was a row of showers.

“Here we are,” I told myself, “Uncle Louis was right.”

I sat next to a window, took off my jacket, twisted it around my right elbow, and broke the window. Then I laid down next to it. We woke up alive.

After a few days of quarantine we were taken by trucks to Allach/Karlsfeld. Just like the camp in Thil, the inhabitants were all Hungarian.

After a few weeks, a new transport arrived, those of my fellow Heftlings who were left behind were forced to march from Kochendorf to Allach, It was a death march. More than half died on the way. My uncle Louis died in the salt mine, before the transport had been sent for them.

I still feel guilty to this day that I did not try harder to talk him into joining me.

~~~~~~~

from the November 2005 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|