|

The Tears of Yefimovich

By Tovli “Linnie” Simiryan (© 2008)

"Die, but do not retreat." - Joseph Stalin

I know all about you. Like the day you came home and opened our wood-carved gate, clad in government khaki, your individuality was stripped from your clothing. You were dressed, but naked. They'd scrambled your name into a comedy of letters. You'd been reduced to numbers pressed into the fine skin of paper describing origin and acknowledgement of existence. The family's passports had been confiscated. Belonging was merely a code devised from three languages, blending distinction, the same way Russia swallowed our borders spitting them beyond the Nistru until our horizons drowned. Our elders had forgotten definition, but no longer had strength to mourn. Mama's voice was like paper folding; bent and protective, creasing secrets until they scurried into dark corners. Her words bounced off a summer breeze, the way gossip clouds a good day, yet entertains.

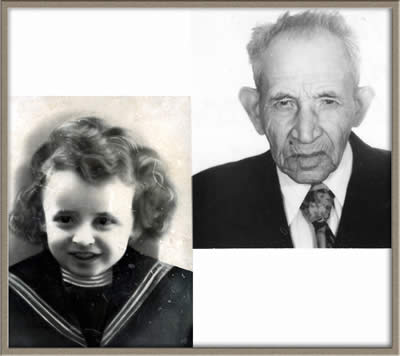

Neighbors did not want to be caught staring. No one dared cry. Mama made me stop playing. I stood as a little soldier, wondering which salute to offer, or whose flag mattered the most. The declaration was announced, first in the Moldovan language and eventually in Russian: "This is your father. Papa is home." After that day, you were always old, and the smell of the gulag remained, even as the gate closed behind you. What I remember most is Mama's voice, her clear eyes, the cold smell of Siberia, and Moldova's secret laughter the spring Stalin died and Papa returned.

The first thing I watch for when I enter a room is order. I wonder how much it will cost to seal boards with paint, or bestow an even coat of pastel chalk that will never wash away. Then, I admire the sound of running water and large picture windows that present orchards, summertime and green grass in need of cutting. I no longer fear soldiers at midnight arriving to take my father from me. As I age, I look for the warm day that held Papa's face the way a mother cups her child's round cheeks in her palms and promises, there will be enough for you, always for you. I cannot enter a room without looking for these things. I am not a young man any more, but I still plan for comfortable places where my father might sit quietly and enjoy the setting sun on cold afternoons.

Papa was small and fragile the spring Stalin's voice called into darkness like a sun going nova, breaking into pieces and falling silent on a cold floor. Moldova welcomed his death, but no one admitted their joy. It is not our way to rejoice at the death of enemies. The old ones caution the young, never ask for a new czar. Stalin's absence symbolized the end of exile, hope for returning lost souls and forgiveness of contrived, storybook crimes. The day my father returned, he resembled someone near death, a moving skeleton emerging from its grave like sharp stones through paper-thin skin. I wondered if what was left of him might miraculously be absorbed into dawn and brighten our eastern horizon or soothe working days with soft evening light. All children believe their father should be omnipotent.

Following his return from Soviet prison, Papa refused to dress in khaki clothes. His name was no longer written on his shirts to ensure identification in case he fell from exhaustion into the deep snow of Siberian wilderness where no one noticed the missing until someone realized they were standing on melting bones during the spring thaw. Papa came home limping; one leg shorter than the other. His legs had been broken in the gulag, but there was no one to set them properly. For the rest of his life his eyes would squint as he climbed steps or tried to leave his chair quickly. "Papa. Are you in pain? Take my hand I will help you."

No matter how frail my father became, he smiled through his pain and kept his secrets in a deep, private place. The morning he returned to Bendery, Moldova, friends and relatives called after him, "Yefim. You have shrunk into a sack of skin and filled it with your bones. But you're home." Although the transgression Stalin attached to Papa's account was ownerless, my father accepted and paid the debt as though it were his own.

Yefim was not Papa's name. Yefim is what Mama called the deep well running silent until all movement is a quiet storm bending trees like an archer's bow about to shoot a prayer into the darkest part of a Siberian sky hoping it will find the morning sun as it warms Moldova. And Papa's prayer? I never learned its sound. He was afraid to teach me the words.

When Papa returned, the neighborhood began calling me Yefimovich—son of Yefim. I attached my shadow to the back of my father's heels and followed him into the house. Our home had not changed since his conviction. Like Papa, it had aged, but stood as shelter. Its frame was weak, thin and colorless. Our coal-burning stove, made from brick, beat like a heart in the center of an old body that could be young with just the right color of curtains hanging in the kitchen. The old stove cooked our food, baked Challah for Shabbat; warmed our slippers and its glow in the middle of the night taught me death could be a quiet flame heating from within, allowing ghosts to visit and dance on the ceiling.

Papa was our ghost. His name was really Haim. It meant life. I was really Haimovich, the son of Haim, a living soul. Mama had sworn my father was alive, but no one knew for how long.

April 7, 1949, two months and two days before my birth, the verdict was announced and spread throughout our village. Mama did not attend the sentencing. No family member attended. Court was a place for the process of deportation, not justice. It was best to stay away.

Mama heard the prosecutor was named Scripnik, a heavyset man who liked to eat, bragged about his family and was Jewish. She visited him privately, begging for mercy and compassion for her husband and those facing Stalin's wrath and hatred of Moldova. This prosecutor didn't dare bestow leniency to fellow Jews. He was not strong enough to stand up for his people. He would have been accused of treason, lost his family, job and eventually been executed if he had shown the slightest benevolence to Papa or our family. There was no hope. I learned not to ask Mama for details. Too much talk spills into the street like warring ants, collecting crumbs left behind until homes become insecure, fear bubbles from the well where everything is hidden and you must change identity in order to return to your loved ones when sin is recalculated and redistributed. Following World War II, you could never be sure who was listening, or who might assume power.

What was Papa's crime? Thirty pairs of pants lined with fleece for the winter months; one hundred and sixty jerseys all sewn by one man with one needle and one spool of thin, thread; then sold for profit. This moment of manufacturing genius supposedly took only two months even though my father had never learned to thread a needle. These were the days before Yefim. It was the time of Haim—a Jew with a name symbolic of distillation of purpose and reason. What other nation would name their sons Life in the middle of Soviet occupation with a cooling holocaust just above the western horizon? What other nation survives by harvesting five-thousand years worth of undergrowth to hide their souls by changing names, yet keeping the same face?

Papa's crime: praying, thinking, talking, acting Jewish and refusal to speak Russian after his country was stolen. Mama put her forefinger to her lips and whispered, "Stalin needed to put a Jew in jail. He sentenced Papa to ten years in Siberian work camps. If Papa had left too loudly, they would have returned for us. Try not to hate Scripnik. His family will answer for his cowardice and G-d should reward him for his level of compassion."

My father was not the only one who left Bendery, Moldova as a prisoner sentenced to make communism work from the inside out by turning trees into railroad ties. He was sentenced for being a Jew caught surviving by sewing too many garments, or experimenting with free enterprise - but, he was one of the few to return. In the spring of 1953, the survivors of Stalin limped home with hollow eyes, their souls bruised and their names translated into Russian.

Mama's voice softened when she spoke about her husband. "Papa refused to speak Russian. They wrote his name using the new alphabet. Haim, the Jew became Yefim, a good communist, but Papa still sang the songs of Moldova and he prayed like a Jew. To protect your father, you became Yefimovich." This was the only secret I understood about my father.

A Jew could hide inside a name like Yefim as though it were a magician's smoked mirror, dimming skin color, hiding an accent or faking language. Sound is belonging. Selecting the right identity or story in the perfect moment can affect survival for generations to come. If we had hidden Papa inside Yefim in the first place, would he have been home the day I was born? If Papa had used the name Yefim instead of standing up as Haim, with prayer exploding beneath a talith, would he have been able to pull me faster in my little sled, the winter following his return? Was it our fault they hated us?

It was a pleasant summer the year Papa came home. Due to Stalin's death, the ten-year sentence was reduced to time served. I was almost five. The khaki fabric covering his thin body burst into a colorful, wool sweater Mama knitted to keep him warm. I liked the way it covered his frail body. He looked well fed when he wore it. Papa was older than Mama. He was quiet, small and the sweater made him larger, giving his presence significance.

"Papa, Papa." My voice as a child hides inside old dreams. It is a thin memory I've placed in the pockets of my soul. "Pull, Papa. Faster, pull." Even his feet were thin. His boots were the ones Mama placed by the fireplace the day they took her husband away. They were now too big and Papa had trouble walking with his injured legs. The snow fell like fat, wet birds who'd forgotten how to use their wings. Papa hooked a webbed strap onto his shoulder and became a mule, an engine sputtering to succeed as a loving father filling space and absence with smiles that warmed me forever.

I am older now than he was when pulling his only child in a sled for the first time. My memory is that of an elderly man with barely enough strength to hoist his heavy winter coat on his back to brave the Moldovan cold. His bones showed beneath his skin, but he pulled and pulled. His injured legs were surprisingly stable and he climbed through deep snow as though he'd rediscovered youth. The sled moved like a frozen, white light along ice. My father had returned to us with secrets and took up very little space. But I flew behind him; warm, smiling, grabbing at air and drops of crystal I had no way of knowing were the shards of his tears broken by the wind that covered my face.

Many secrets are scattered like dead seeds inside my memories. Papa had no stories of the gulag. It was as though giving voice to this dark place would bring unending winter filled with starvation, or skin would blacken and fall to earth from an evil frost. I wondered if he was ashamed or frightened someone might call him Haim, the Jew if he told his story aloud. It wasn't until I buried Papa in America and the Rabbi handed me his prayer-shawl, I understood the price Papa had paid to speak with G-d inside our Russian occupied homeland. Because of them, my father was afraid to pray in front of his son.

Moldovan life is based on simplicity and hard work. Papa was a merchant, but he'd also been convicted of the crime of capitalism and selling for profit. The Soviets no longer allowed him to sell merchandise. His life's work was taken from him as additional payment for being the Jew who sewed too many jerseys, selling them quickly to feed the non-Russian community.

Life became harder and less joyful. Papa found work at the ropeyard. He twisted hemp until it coiled into massive brown snakes covering his feet and calves. His hands bled and he remained thin. He sat behind a hackling machine, his cloth facemask turning black. Dust entered his lungs instead of air. Were it not for Shabbat and Sundays at the Shuq, I am certain Papa would have disappeared like cigarette smoke. I skipped school to bring him lunch. He gently rubbed my smooth face with the back of his hand, begging me to return to my classroom quickly so I'd be selected for a good job when I was older.

Papa did not speak Russian. Some said he was too old to learn the new language when the Soviets took Moldova. Others decided he was uneducated and unable to learn. The truth was Papa refused to speak Russian, even to his only child. On the streets, he spoke the Moldovan language—Romanian. It was a beautiful, flowing dialogue filled with melody and light-hearted song. He spoke Yiddish in our home. He wrote the Hebrew letters of Yiddish as though each symbol was a portrait of something only he could tell G-d. His penmanship was that of an artist.

"Papa. Teach me to write Yiddish; teach me the language of our people so I can talk with G-d. "

The old man smiled into my eyes answering, "What do you need it for? Yefimovich can pray in Russian." Until his death, I listened to him in Romanian and Yiddish and answered him with Russian.

Sundays Papa always appeared at the Shuq. It was his favorite day. On this day, the Romanian and Moldovan peasants sold their goods. Papa was like a shadow. In our time, everything was Defitsit—merchandise sold at profit under the table. He could speak the language of Romania. The Moldovans protected him, hid him and watched as he sold everything they'd commissioned into his care at substantial profit. Papa made them rich, pocketed a few rubles and sang the songs of Moldova on his way home.

What frightens the father is often found in the soul of his son. I was a good student and as an adolescent, I accepted an apprenticeship as a metalworker. The Russians decided to lay gas pipes in our neighborhood. We tripped over the debris of pipe and metal in the streets for weeks. We did not have indoor plumbing. Each morning my parents washed themselves with ice water collected in a wooden barrel that sat in our yard. Friday afternoon, Papa and I bathed at the public bath-house with the other men.

My teacher helped me find material to fashion a sink and bathtub. One moonless night, Papa and I dragged a three by twelve foot, heavy walled pipe discarded by Russian workers into our yard. Hidden by darkness, we dug a ditch, positioning our confiscated pipe at just the right angle and dropped it into the soil. It became our septic system. Papa thought it was a good use of Soviet occupation. I was delighted my parents could bathe indoors in the comfort and warmth of our home, but what really mattered was the sparkle in my father's eyes as he watched his son create value from thin air.

My teacher was proud of his young apprentice and wrote a newspaper article in Russian about ingenuity and survival. It appeared in the Bendery paper the following week. I was frightened and certain the Soviets would accuse me of stealing their pipe and materials. The night following the publication of my brilliant attempt at comfort and survival, I dreamed I was a prisoner dressed in my father's government issued khaki uniform. I sat inside a boxcar of a train bound for the gulags. A cold voice with an uncanny resemblance to Nikita Khrushchev, spoke to me, explaining the language of my prayers could not be understood, not even by G-d.

As I age, I want to plant seeds I have saved from Moldova. They are threads from my father's life, memories that are dormant and have little potential of producing flowers. Papa. What happened in the gulag? You survived. You returned before your ten year sentence ended as though nothing mattered. I know you did not forgive them. Did they forgive us for being Jewish? Did the name Yefim please them enough so they forgot your real identity and let us live? Papa, why are we hated?

Although my family lived in the town of Bendery for as long as anyone remembered, we were all from different countries. Every passing government wanted to give Moldova a new name: Bessarabia, Romania, Transylvania, Moldavia and now, Pridnestrovie—the new Russia. My family was religious. The men prayed for five generations within the staggering architectural beauty of Bendery's old synagogue. The Soviets closed it out of kindness. "Dangerous. It is too dangerous for prayer. The foundation will collapse. The roof will cave in. We are closing the synagogue for your safety and survival." Half a year later, it was "repaired" and opened as a boxing and wrestling gymnasium—no Jews allowed.

The men rented a large room where they could pray. I begged, "Papa. Take me with you. I want to learn your prayers." But the KGB were watching. Papa knew their faces and smiles. He was afraid they would remember he had a son and he refused to teach me G-d's language or allow me to pray with the men in public. Papa never stopped praying. Each day before and after work, every holiday and Shabbat, he disappeared with a handful of survivors from the work camps and told his secrets to G-d. It's a wonder they all did not die in some Russian prison, their families beside them.

I want to drop my memory-seeds into tiny American holes I've prepared with my fingers and see what sprouts. I promised my parents America was a place of hope and inclusion. I brought them here when Gorbachev, Reagan and Bush agreed to open doors and let a sweet breeze beckon. Papa was afraid of America. He only completed kindergarten, but understood war, its cause and price: "The Soviets and Americans make weapons. It's an art form for both governments. They need places to practice the technology of battle. Are you sure the skies above America are clear of bombs? Are there places for Jews to hide and pray in America?"

It's been over a decade since we departed Moldova. There is not much left of my relatives. Mama is almost one hundred years old. Soon, I'll be all that remains of a once strong, loving and hopeful family. In America I have learned to sleep late and not work so hard. I no longer dream of prisons and trains traveling toward Siberia. My only fear is no one will recognize the spores of my father's life if I keep them inside my pockets. Their blossoms have the potential to redefine color and genetics. No one can be sure which window his stories will open. I collect what remains from the void Stalin left inside my father and sprinkle seed, hoping a new color appears in the American sunset and shines into an appreciative pair of eyes.

My father lasted two years in the United States. The dark dust he'd collected inside his lungs as a factory worker developed into disease. Cancer spread through his body so quickly there wasn't time to kiss him good-bye. The Rabbi helped me find a grave where sunsets were visible. When I dream of Papa's voice and plant his sound inside stories, I pray the pollen I have saved from his life will burst into the lives of others, become useful and fill an American sky with trust instead of war. Someday, I hope Papa recognizes the colors of his life in an American sunset as its shadow falls across his grave.

Papa's talith is over a hundred years old. A Lubavitcher Rabbi gave it to him in Moldova so he could pray secretly with the other men. "It's an old prayer shawl," the Chabadnik admitted. "But it's holy. It will cover you completely and you can change the world as you tell your secrets to G-d. Many Jews have prayed beneath it. It is stained with generations of tears passed from fathers to their sons. We must not ignore the tears of our people."

* * *

When Papa died, an American Rabbi buried him. He handed me Papa's talith, saying "It's an honour for you to pray inside your father's prayer shawl. It's holy. It has wiped away many tears." Strange, how he would know its history. Then again, many sons have shed the same tears while trying to pray like their fathers.

I wrap myself inside Papa's prayer shawl each morning and the first rays of dawn remind me of Moldovan summers. Beneath his talith, I dream of Bendery, the old synagogue and Papa rising before sun-up to begin his work. When I bless Papa's talith, and kiss the tzitzit, I realize, this is all that is left of him. I stumble over G-d's language. I want to speak quickly to G-d, like Papa and the other Moldovan Jews. I worry that G-d will not understand me because Papa was afraid to teach me the secret melodies of prayer. His life as a father was filled with the fear the wrong person would hear his son praying and send his little boy to prison. He was afraid I'd look and sound too Jewish. He feared I'd become too much like him.

Each morning, beneath Papa's talith, I lose my voice. I stand shoulder to shoulder with every kind of Jew. It is America. Everyone belongs. The Rabbi prays faster than I can think. He does not pray quickly because he is afraid. Instead, he worries G-d will take so long to listen, his congregation will become bored and one by one we'll disappear while his back is turned. America is like that, porous in boundary and belonging; forgiving of fear and those who vanish in deep snow. It is important for me to pray like my father.

I talk to my father every minute of my day. I always tell him the same story: Papa, the older I become the longer my prayers take. My voice does not sound like yours. It is heavy and deliberate. I don't whisper. The holes I've prepared for your stories have sprouted seedlings. Papa, American soil is rich and young. There are more than six million of our people living in this country. Some are religious; others are Americans before they are Jews. You choose your own name in the United States and I am called ben-Haim, the son of a Jew who survived Stalin and Soviet occupation.

"Rabbi", I asked one morning. "I want to pray with the melody of my father. My father was afraid to teach me to pray. I never learned to pray like the other men of my community."

As usual, the Rabbi was in a hurry. He shrugged his shoulders and smiled "Your prayers will end up in heaven no mater what accent you pray with."

Another man interrupted and asked why I came to America. "Freedom to pray as a Jew," I answered.

"What, you can't pray Jewish in Russia?"

This man had a pleasant smile and wore a brand new talith the size of a band-aide. It was draped around his neck, as though chosen in the same way a man chooses a necktie to accent his morning apparel. I wondered how he could wrap himself inside such a tiny piece of cloth and shoot his secrets through darkness into G-d's ears. How could he come up with prayers beneath a garment so new and pristine it had not collected one tear?

I asked, "Brother, where have you been living? Are you new to the world? My father was one of many sentenced to ten years in a gulag for being a Jew. Like the others, he hid the sound of his prayers from the ears of his children. He thought his generation was the last of our nation—that Stalin had won and the Soviets owned the world. He could not walk to work in the morning without wondering if he'd return home at night. All that is left of him is me and tears that stain the talith I wrap myself in to pray my secrets to G-d."

"Really?" he answered, and I never saw him again.

That night Papa visited my dreams. We must have been in Moldova waiting for a train, but it rumbled past our stop like a flock of low-soaring, fat-bellied geese.

"War is eminent." Papa concluded.

"War, Papa? Why do you think there will be war?"

"When overweight trains begin missing their stops, it means they are transporting ammunition. New weapons need testing. There will be a war."

"How can we stop it, Papa?"

"Pray, Yefimovich. Make your secrets and prayers sail like arrows into heaven. Pray beneath our talith until it is wet from your tears."

"But I've lost the language, Papa. I am not sure my prayers have wings."

"Speak, Yefimovich, as if your words were crying. G-d needs to hear a new song and is waiting behind the most colorful sunset I've ever seen, just for the sound of your melody.

Tovli “Linnie” Simiryan is an award-winning writer living in West Virginia with her husband, Yosif. The Simiryan family came to America as refugees from the former Soviet Union ( Moldova ) in 1992. Tovli’s short stories, essays and poetry have appeared in a variety of publications. Ruach of the Elders, Spiritual Teachings of the Silent, a collection of short stories and memoirs will be marketed by HDM-Publishers in January 2009.

~~~~~~~

from the November 2008 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|