Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

American “Righteous Among the Nations”

By Jerry Klinger

Frodo: "I wish none of this had happened."

Gandalf: "So do all who live to see such times,

but that is not for them to decide.

All we have to decide is what to do

with the time that is given to us."

- Lord of the Rings

“Dear Rabbi,

I am working on an article about Varian Fry and Martha and Waitstill Sharp, recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem. Is a Jew required to risk his life to save a strangers life if he knows it will endanger his life and the lives of his family and his community? The answers I have found so far have not been very satisfying, especially Rabbi Akiva's from the Talmud. The risk is not to the individual who jumps into the water to save the stranger or the issue of sharing or not sharing the last bit of water but what happens to those behind? Can we make decisions of life and death based upon our own code of religious morality if it affects other people's lives?”

“Dear Jerry,

According to the halacha, one is only required to risk his life in as much as any normal person would do so in order to rescue his own possessions. (However, “Midat Chassidut” - (“according to the attributes in the performance of acts of kindess”) one should risk his life to rescue another Jew if there is more than a fifty percent chance he will succeed). So no, one is not obligated to put their life in definite danger to save another.

Wishing you all the best,

Rabbi Y.”

“Thank you Rabbi,

Your answer has left me with a terrible conclusion. No one was responsible, or morally obligated, when Jews were being murdered during the Holocaust. The probability of death for helping Jews was greater than 50%. Another way of saying the same thing is, not to act to prevent or thwart the murderous activity of Nazis and their supporters because of the risk to one's own life or their family was the correct thing to do. I would have to understand that the nearly 200,000,000 Europeans and countless others around the world who were silent are absolved of any responsibility. I find it difficult to accept that answer because it means that the Nazis who went to trial for their actions used as a defense that if they did not act and follow orders they and their families most likely would have faced death. By extension then you are suggesting they should have been found not guilty. They were under no obligation to risk their lives to save Jews. The final logical conclusion is that only God should be held responsible for the Holocaust.

The actions of people like Varian Fry, Martha and Waitstill Sharp, who did not focus on saving Jews in particular, but on saving a specific group of people is the most important understanding. Approximately 80% of Christian rescuers did rescue Jews because they were Jews with the full understanding of the risk to themselves or their families. They all had some level of moral foundation that came from their Christian backgrounds, The Dutch Reformed Church, the French Evangelical Church, elements of the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox Churches had strong influences on their decisions to save Jews. Surely there must be some requirement or mandate in Jewish law to risk one’s life, not to sit and let murderous evil occur, even if the odds are poorer than 50%, to affirm God's commandments not to kill but to protect life?

Forgive my request again, your guidance is needed.”

“Dear Jerry,

Sorry for the delay. I think I first should clarify that although we are discussing if one has to endanger their life in order to save another, the Halacha is clear that if one were to tell someone either I'll kill you unless you hand me over someone to be killed, one is obligated to give their life, rather than give over someone to be killed.

So no, someone cannot claim "I was forced or under orders."

With regards to the larger question about endangering one’s life to save another, here is an article I found online that gives some outline http://www.israelnationalnews.com/Articles/Article.aspx/9211 (I cannot say that I went through the article in depth, so I won't vouch for everything, but as an overview it should suffice).

Let me know if this helps.

Wishing you all the best,

Rabbi Y.”

Varian Fry was born in New York City on October 15, 1907. As a young person, his perceptions of life were shaped by his grandfather, Charles Fry. For many years Charles Fry had been the western agent of the Children’s Aid Society caring for the “Orphan Trains” carrying abandoned and orphaned New York children to new homes in the West. Summers, Varian observed his grandfather running the Society’s summer home for destitute and abandoned children at Graveshead Bay, New York. Charles was a social worker. Social workers were called “child rescuers.” Charles love for humanity deeply influenced Varian.

Varian graduated from Harvard in the depths of the Depression. He married a Boston girl, Eileen and they sought work. Varian found a job as editor of a foreign affairs journal in New York. The summer of 1935, he traveled to Germany. He was horrified at the sight of Jews being bullied and beaten by S.S. in the streets of Berlin. Varian sensed the stench of impending disaster for humanity.

German and Austrian refugees, a large percentage of who were Jews, desperately sought safe havens. Many tried to come to the United States. The American sanctuary was tightly obstructed and virtually closed, especially to Jews, by the U.S. State Department.

Breckenridge Long was a personal friend and political appointee of President Franklin Roosevelt.

“He was a personal friend of future President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whom he had known as Assistant Secretary of the Navy during the Wilson Administration, and generously contributed to his 1932 Presidential campaign. Roosevelt rewarded him with the position of U.S. Ambassador to Italy. During his ambassadorship he was criticized for advising the president against imposing an embargo on oil shipments to Italy in retaliation for Mussolini's invasion of Ethiopia. He was a member of a special mission to Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay in 1938 and adviser to the U.S. Department of State in 1939. He was assigned to handling war emergency matters and assistant secretary in charge of the Visa division.

Long came to believe that he was under constant attack from "the communists, extreme radicals, Jewish professional agitators, [and] refugee enthusiasts". Many of his views were shared by his subordinates.

In an intra-department memo he circulated in June 1940 Long wrote: "We can delay and effectively stop for a temporary period of indefinite length the number of immigrants into the United States. We could do this by simply advising our consuls to put every obstacle in the way and to require additional evidence and to resort to various administrative devices which would postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of the visas." Ninety percent of the quota places available to immigrants from countries under German and Italian control were never filled.

In November 1943, when the House was considering a resolution that would establish a separate government agency charged with rescuing refugees, Long gave testimony saying that everything was being done to save Jewish refugees, which caused a loss of support for the measure. However, his testimony was false and misleading: Long exaggerated the number of refugees and included non-Jewish refugees in his count of 580,000.

Long is largely remembered for his obstructionist role as the official responsible for granting refugee visas during WWII. He "obstructed rescue attempts, drastically restricted immigration, and falsified figures of refugees admitted. The exposure of his misdeeds led to his demotion, in 1944. He has become the major target of criticism of America's refugee and rescue policy.”

Long reflected a deep seated anti-Jewish attitude within the State Department dating back to the Mordecai Manuel Noah controversy when (later President) James Monroe was Secretary of State, 1813.

President Roosevelt, ironically idolized by the American Jewish community then and for generations of ties through the Democratic Party later, agreed with Long.

Long recorded in his diary a meeting with President Roosevelt, Oct. 3, 1940. The President concurred with his policy that denying certain elements (it was mutually understood to be Jews) visas to the U.S. was a good idea.

“So when I saw him [FDR] this morning the whole subject of immigration, visas, safety of the United States, procedures to be followed; and all that sort of thing was on the table. I found that he was 100% in accord with my ideas. He said that when Myron Taylor, [the President's personal representative to the Vatican], had returned from Europe recently the only thing which they discussed outside of Vatican matters was the visa and refugee situation and the manner in which our Consulates were being deprived of a certain amount of discretion by the rulings of the Department...The President expressed himself as in entire accord with the policy which would exclude persons about whom there was any suspicion that they would be inimical to the welfare of the United States no matter who had vouchsafed for them and irrespective of their financial or other standing. I left him with the satisfactory thought that he was wholeheartedly in support of the policy which would resolve in favor of the United States any doubts about admissibility of any individual.”

Breckenridge Long successfully applied his powers over refugee immigration to the United States. Between 1941 and 1945 about 15,000 visas were granted, less than 10% of the quota that was permitted. It is unknown how many lives may have been saved had the quotas been allowed to be filled.

Hitler came to power, Jan. 30, 1933. With his rise more and more small, splintered anti-Nazi organizations grew up. Many were just a few members strong, most were ineffectual.

“As Hitler consolidated his power throughout the mid-1930s, a steady stream of displaced intellectuals and politicos arrived in the United States. Among these arrivals was a number of émigré resistance fighters, some of whom would play integral roles in the formation of the Emergency Rescue Committee. The most important among them was the Austrian-Jewish socialist Karl B. Frank (a.k.a. Paul Hagen; Wilhelm [Willi] Mueller; Maria). Frank, who likely adopted the pseudonym Paul Hagen partly because he did not wish to be associated with the notorious Nazi leader Karl Hermann Frank, was an active member of both Austrian and German Social Democratic splinter groups……

Frank believed that the elements of social democratic resistance still existing within Nazi Germany were strong enough to instigate a mass revolution that would establish a new democratic government after the Allied military victory. A group of like-minded activists, including Frank’s wife Anna Caples, the Austrian Socialists leader Joseph Buttinger (a.k.a Gustav Richter), and Ingrid Warburg, gathered in New York around Frank in the years 1937-39……….

The eminent American theologian Dr. Reinhold Niebuhr set up the informal American Friends of German Freedom in 1936 (two of his earliest employees were Eileen Fry (wife of Varian) and Anna Caples-Frank) to provide funds for the mysterious drifter of the resistance, Karl Frank. Niebuhr apparently heard of Frank through the American socialist leader Norman Thomas, and through the British socialist and supporter of the Volksfront-Gruppe, Stafford Cripps. On the advice of Thomas and Cripps, Niebuhr went to Europe seeking Frank in 1935, and the resulting meeting convinced him that Frank’s was a worthy cause. Niebuhr founded the American Friends of German Freedom (AFGF) in the following year, funding Frank’s activities through a number of New York philanthropists, many of whom would support any group Niebuhr endorsed. Throughout most of the 1930s, Niebuhr had been involved in the Socialist party and agreed with its policy of pacifist nonintervention, but he radically changed his position to a more militaristic activism following the 1937 World Conference on Church, State, and Community held at Oxford. After his ideological shift, he became what could be characterized as a “left-wing, anti-Communist Democrat”…….

In his capacity as Research Director, Frank “organized short-wave radio broadcasts to Germany, oversaw two periodicals about German affairs, helped refugees arriving in New York, and kept up his ties in Europe. Niebuhr’s biographer Richard W. Fox notes how Frank “regarded the American Friends as his personal instrument” for continuing the resistance against the Third Reich…………….

The United States government and the general American populace may have been apathetic to the plight of the refugees, but located in New York City was an intertwining network of relief agencies, rescue committees, and refugee associations. By the end of the war the list of organizations devoted to helping European refugees was extensive…………

The defining moment for the formation of the Emergency Rescue Committee (Varian Fry was to be a member of the ERC) finally came shortly after the fall of France when the Nazis announced terms for the armistice. Under Article 19 of the June 22, 1940 peace agreement, France was required to “surrender on demand” any German refugee to Nazi authorities………..

The problem with all of New York’s agencies was that their primary bases of operation were on the wrong side of the Atlantic—the first course of action for the ERC was to send a representative to France to personally carry out its delicate rescue mission from within the Nazi puppet regime. Before the committee decided on its agent, however, it needed a specific list of refugees to rescue; the sheer number of displaced persons fleeing the Nazis was overwhelming, and if the ERC did not discriminate it would not be able to effectively carry out any operation. Those who spoke at the Commodore luncheon had implied that the most pressing concern was for the many artists, writers, musicians, and intellectuals in danger. Whether or not the ERC leadership held a more egalitarian concern for the common refugee, the only way the group could raise any kind of funding would be to focus on rescuing Europe’s elite….

If only for the sake of reconnaissance, the committee needed to send an agent to France immediately. Sometime in mid-July of 1940, Warburg held a joint staff meeting of the ERC and AFGF at her apartment for the purpose of choosing an agent. In attendance were a number of professors, foreign correspondents, and union leaders, all candidates for the position. Also there was Varian Fry, who was attending as a friend of the AFGF circle and as an editor of Common Sense, The Living Age, The New Republic, and the Foreign Policy Association. Of the candidates present, none were acceptable. But, according to Mary Jayne Gold, Fry was “deeply impressed by what he heard that night and after talking it over with his wife, Eileen, he called up the secretary of Emergency Rescue and let them know that he was available in case nobody else turned up.” Karl Frank, probably still holding strong reservations about sending a naïve Harvard boy off to Vichy France, returned Varian’s call a few days later and invited him to an interview that evening. After briefly outlining the dangers of refugee work, Frank gave Fry the job. The ERC arranged for Fry to travel to Lisbon via Dixie Clipper, then by train to his destination Marseilles, the refugee epicenter. Fry’s subsequent work over the next thirteen months through the offices of his Centre Américain de Secours is well documented….

The staff of the ERC set up case files for each of the hundreds of refugees on its list…….

The main qualifications for acceptance was that the client have fought in some way for the cause of democracy, and that he or she have no affiliation with the communists. The former stipulation was very flexible, but the latter was rigid. Not only were the ranks of the ERC, the IRA, and the AFGF thoroughly social democratic, but Varian Fry, who probably had the greatest power in accepting or rejecting clients, was also a dedicated pro-democrat—not to mention the fact that the U.S. government would not condone any group with communist sympathies. Once a refugee’s political affiliation was verified, it was decided that an allotment of $300 per capita (later $350) would be sufficient to fund the rescue…….

If the revised $350 per capita plan for each individual refugee is applied to the adjusted total, the ERC had the ability to rescue over 500 individuals over the course of a year and a half. That the organization actually rescued nearly twice that number by the end of 1941 is a testament to the superb work of Fry in Marseilles.

The money was flowing steadily through the ERC offices and out to Marseilles, but the real problem was the acquisition of visas for the many desperate refugees in need.”

“In 1939, Bingham was posted to the US Consulate in Marseille, where he, together with another vice-consul named Myles Standish, was in charge of issuing entry visas to the USA.

On June 10, 1940, Adolf Hitler's forces invaded France and the French government fell. The French signed an armistice with Germany. In Article 19 of the document, the French agreed to "surrender on demand all Germans named by the German government in France." Civil and military police began to round up German and Jewish refugees who were marked for death by the Nazis. Several influential Europeans tried to lobby the American government to issue visas so that German and Jewish refugees could freely leave France and escape persecution.

Anxious to limit immigration to the United States and to maintain good relations with the Vichy government, the State Department actively discouraged diplomats from helping refugees. However, Bingham cooperated with Varian Fry in issuing visas and helping refugees escape France. Varian Fry had come to Marseilles to give 200 grants to "some of the best scientists and European scholars" (1) and help them settle in the US. Hiram Bingham worked with him, and instead of 200, gave about 2,000 visas, most of them to well-known personalities, speaking English, not too left-wing and not looking too Jewish, among whom Max Ernst, André Breton, Hannah Arendt, Marc Chagall, Lion Feuchtwanger and Nobel price Otto Meyerhof. All the others anonymous waiting night and day in front of the American consulate were not lucky enough. Varian Fry explains in his book "Surrender on Demand": "we refuse to help anyone who is not recommended by a confident person."

He also sheltered Jews in his Marseilles home, and obtained forged identity papers to help Jews in their dangerous journeys across Europe. He worked with the French underground to smuggle Jews out of France into Franco's Spain or across the Mediterranean and even contributed to their expenses out of his own pocket.

In 1941, the United States government abruptly pulled Bingham from his position as Vice Consul and transferred him to Portugal and then Argentina. When he was in Argentina, he helped to track Nazi war criminals in South America. In 1945, after being passed over for promotion, he resigned from the United States Foreign Service.

Bingham did not speak much about his wartime activities. His own family had little knowledge of them until after Bingham's death. In 1991, Bingham's wife Rose and son Thomas found Marseilles documents in the Connecticut farmhouse which they forwarded to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum; his youngest son then discovered a tightly wrapped bundle of letters, documents and photographs in a cupboard behind a chimney in the family home. The materials told of Bingham's struggle to save German and Jewish refugees from death, details long hidden from the public.

After considering Bingham's deeds during the war years in Marseille for a number years, Yad Vashem issued the Bingham family a letter of appreciation on March 7, 2005. Although not a Righteous Among the Nations designation,

- because he saved selected personalities and never was himself in danger -

the letter noted the "humanitarian disposition" of Bingham IV "at a time of persecution of Jews by the Vichy regime in France.... [in] contrast to certain other officials who rather acted suspiciously toward Jewish refugees wishing to enter the United States.

Hiram Bingham IV, US commemorative stamp

On June 27, 2002, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell presented a posthumous "Courageous Dissent" award to Bingham's children at an American Foreign Service Officers Association awards ceremony in Washington, DC. Since December 1968 his son Robert Kim Bingham, Sr. had lobbied the U.S. Postal Service to issue a stamp depicting his father in recognition of his humanitarian deeds. After the proposal received wide bipartisan support in Congress, a commemorative stamp portraying Hiram Bingham IV as a "Distinguished American Diplomat" was issued on May 30, 2006.

On October 27, 2006, the Anti-Defamation League posthumously presented Bingham its "Courage to Care" award at the ADL’s national conference in Atlanta. In November 2006, the U.S. Episcopal Church added Bingham to a list of "American Saints" published in the book A Year with American Saints with a summary of his life and character.”

Hiram Bingham IV ruined his career to do what he knew was right.

“In Marseilles, Fry offered aid and advice to anti-Fascist refugees who found themselves threatened with extradition to Nazi Germany under Article 19 of the Franco-German Armistice-- the "Surrender on Demand" clause.

Working day and night, in opposition to French and even obstructionist American authorities, Fry assembled a band of associates and built an elaborate rescue network.

Convinced that he could not abandon the operation while desperate refugees needed him, Fry extended his stay into a 13 month odyssey carrying on without his passport, under constant surveillance and, more than once, questioned and detained by the authorities.

Establishing a legal French relief organization, The American Relief Center, Fry worked behind its cover using illegal means -- black-market funds, forged documents, secret mountain and sea routes-- to spirit some 2000 endangered people from France.

Among the refugees were notable European intellectuals, writers, artists, scientists, philosophers and musicians. Their arrival in the United States significantly changed the character of American culture.

Fry was recalled by the American government and ignored repeated entreaties. He was finally ousted by the Vichy French government under an "ordre de refoulement" as an "undesirable alien" for protecting Jews and anti-Nazis, in September 1941.

When Fry returned to New York, he recounted his story and tried to warn of Hitler's impending massacre of the Jews.

His activities in France prompted the Federal Bureau of Investigation to open a file on him and to keep him under surveillance which prevented him from ever working for the United States government.

Shortly before his death, Mr. Fry was awarded the Croix de Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur by the French government, which was the only official recognition he received before his death.

Fry died unexpectedly and alone in 1967 while revising his memoirs. He left behind a wealth of written and photographic materials that document his experiences in France.

Varian Fry was posthumously honored by the United States Holocaust Memorial Council with the Eisenhower Liberation Medal in 1991. His work in France, in 1940-41, to assist and rescue endangered refugees was the subject of an exhibition at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1993-94.

Varian Fry was posthumously honored by Yad VaShem, The Holocaust Heros and Martyrs Remembrance Authority, Jerusalem as the first American Righteous Among the Nations in a ceremony attended by Secretary of State Warren Christopher in February 1996. The additional honor of "Commemorative Citizenship of the State of Israel," awarded to selected Righteous Among the Nations "who rekindled the light of humanity during the Nazi era in Europe" was given to Fry on January 1, 1998.”( Memo to Congressmen" by Susan Morgenstein, curator of the Varian Fry special exhibit at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Updated by Walter Meyerhof)

Varian Fry sacrificed his future to do what he knew was right. He was largely forgotten until Pierre Savage, a founder of the Le Chambon Institute ( http://www.chambon.org/chambon_institute_en.htm), diligently worked to bring his story forward. Fry’s recognition as a Righteous Among the Nations is primarily because of Savage.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Martha Joukowsky is the daughter of Waitstill and Martha Sharp she wrote about her parents for Yad Vashem.

“Waitstill Sharp was a minister in the Unitarian church in Wellesley, Massachusetts, and his wife Martha a noted social worker. In 1939, the Sharps accepted an invitation by the Unitarian Service Committee to help members of the Unitarian church in Czechoslovakia. Arriving in Prague in February 1939, the Sharps also aided a number of Jews to leave the country, which had come under Nazi control on March 15th. The Sharps continued their charitable work until August 1939, leaving Prague when warned of their possible arrest by the Gestapo. On June 20, 1940, Waitstill and Martha Sharp landed in Lisbon, Portugal, on a mission to help refugees from war-torn France. Making their way into Vichy-controlled France, that had allied itself with the victorious Nazi Germany; they sought ways to help fugitives from Nazi terror, Jews and non-Jews alike.

They then learned that Lion Feuchtwanger, a world famous German-Jewish author of historical fiction needed to be taken out of France urgently. In 1933, with Hitler’s rise to power, Feuchtwanger had settled in France where, together with other German anti-Nazi intellectuals, he continued his literary work as well as his anti-Nazi writings. He was numbered 6th on a list of persons whose German citizenship was annulled for their anti-Nazi stance. With the outbreak of the war in September 1939, Lion Feuchtwanger was ironically interned by the French government as an “enemy national” and held first in Camp des Milles, near Aix-les-Bains, then in St. Nicholas, near Nîmes. With the defeat of France in June 1940, Feuchtwanger’s life was in danger, since under the French-German armistice agreement, the French government had undertaken to hand over to the Nazis any Germans upon request, and Feuchtwanger was one of the persons on top of the Nazi wanted list. His wife Marta tried desperately to save him, and asked Myles Standish, of the US consulate in Marseilles, to help liberate her husband from internment.

This was done, with Feuchtwanger fleeing dressed as a woman. Taken to Marseilles, it was now urgently necessary to get him out of the country, for fear that the French police, then under Vichy control, would be looking for him. Learning of Feuchtwanger’s plight from Varian Fry, an emissary for the US Emergency Rescue Committee, Waitstill and Martha Sharp took it upon themselves to organize Feuchtwanger’s escape. A new identity card was produced, where he appeared as Wetcheek (the English translation of the German Feuchtwanger). The Sharps then rented a room in Marseilles near the main train station, from where one could cross via an underground passage directly into the station and thus avoid the police control at the station’s entrance. In September 1940, Martha Sharp, dressed as a native peasant woman, accompanied Lion and Marta Feuchtwanger by train to Cerbere, on the Franco-Spanish border, where Waitstill Sharp was waiting for them. He told them that he had bribed the French border guards to allow the flight of the Feuchtwangers, but urged them to be careful, for he could not guarantee that the same guards would be on duty when the Feuchtwangers would attempt their crossing. It was decided that Marta Feuchtwanger would go first, and with the help of the cigarettes that she freely distributed to the guards, she distracted them for enough time to be allowed to pass the frontier undisturbed. As for Lion, he also crossed over successfully with the help of his false identity card under the name of Wetcheek.

The Sharps waited for them on the Spanish side, and the whole party continued on to Barcelona. The intention was to reach Lisbon, Portugal, and catch a boat sailing for New York. To get to Lisbon, the party of four first had to head to Madrid, but were afraid to use the sole airline making that route, the German (and Nazi-controlled) Lufthansa, so instead they went by train. Waitstill bought a first-class ticket for Lion, hoping that the Spanish police would be less diligent in inspecting travelers in that compartment. He also gave him a briefcase bearing the large heading “Red Cross.” Lion’s wife Marta traveled third class. Throughout the long trip to the Spanish-Portuguese border, Waitstill watched over Lion Feuchtwanger, keeping inquisitive travelers at a safe distance, so as to lessen the danger of his disclosure by the Spanish police, and the risk of his being returned to Vichy French hands. The Fascist dictatorship in Spain, headed by Franco, was at the time considering aligning itself with Nazi Germany, and would certainly not have hesitated to hand over Lion Feuchtwanger to the Nazis if they had asked for him. Arriving safely in Lisbon, also at the time a near-Fascist country headed by Salazar, the Sharps arranged for the Feuchtwangers to quickly board a ship heading for New York, and they sailed at the end of September 1940. At the time, they were assured that the US government had allowed their entry into the United States. In 1976, Marta Feuchtwanger gave a lengthy account of their escape from France with the assistance of Waitstill and Martha Sharp.

Having accomplished this, Martha Sharp returned to France, and journeyed to Vichy to plead for permits (laissez-passer) for a group of children-9 of them Jewish- to leave the country, which she eventually received. On November 26, 1940 this group left France, including the three Jewish Diamant sisters (Amalie, Evelyn and Marianne), and Eva Esther Feigl, all of whom, thanks to Martha Sharp’s efforts, were armed with US visas. Born in Vienna, Austria in 1926, Eva Feigl had fled with her parents in 1938, and arrived in France. Arrested as “enemy aliens,” the Feigls desperate sought ways to leave the country. Luckily for them, the Sharps were able to add Eva Esther to this group of children, and take her out of the country. Her parents stayed behind. Mrs. Feigl lives in New York, and gave testimony of her timely rescue by the Sharp couple. After the war, Martha Sharp helped raise funds for Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization, and was active in helping Jewish children reach Israel under the Youth Aliyah program. In that capacity, in 1947 she journeyed to Morocco, and in 1951, to Iraq, to coordinate clandestine emigration possibilities for Jews desirous to leave for Israel. She died in 1999; Waitstill had passed away in 1984.

In light of the risks taken by the Sharps – first of being apprehended by the French authorities for helping Lion Feuchtwanger, a fugitive from French law, to avoid arrest, coupled with the offense of bribing French border guards, and the equal risks of arrest while traveling incognito through Spain, a country leaning toward Nazi Germany, and keeping in mind the Sharps’ meritorious assistance to other Jewish fugitives of Nazi terror – Yad Vashem decided on September 9, 2005 to confer upon the late Waitstill and Martha Sharp the title of Righteous Among the Nations.

A medal and certificate of honor was presented to the Sharps’ daughter, Martha Sharp Joukowsky, in a ceremony at Yad Vashem, on June 13, 2006, in the presence of a large audience, including members of the Sharp family, and Mrs. Eva Esther Feigl, one of the Jews rescued by the Sharps.”( http://www1.yadvashem.org/righteous_new/usa/sharp_print.html)

Having been approached by the Unitarian Service Committee, Reverend Waitstill Sharp and his wife Martha decided to put themselves at risk to save lives. (http://www.uusc.org/files/TheSharps.pdf)

It was a statement of faith. They left their children in the States and went to do what they knew was the right thing.

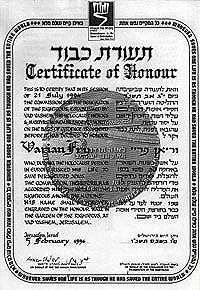

Certificate of Honour – Yad Vashem

Varian Fry and the Sharps saved Jewish lives. In both cases the intent was not specifically to save Jewish lives. The intent was to save anti-Nazis who in many cases happened to be Jewish. Varian Fry and his team realized that they had to make a difficult decision. In order to save lives they had to be very specific in who would be saved. They made lists and focused on the intellectual and artistic community. It can be argued that the decision to rank the value of life by intellect and accomplishment was cynical but it was also a reflection of the practical reality. They could not save everyone. They had to pick and choose in order to save some. The support from their backers was not for the universal saving of Jews; it was focused on leftist social and societal values. Refugees of conscience and faith were not part of the list of chosen for focused rescue.

The Sharps did not make the same distinction as did Fry as to whom to save. Their witness to their faith was simply to save life, Jewish or otherwise. The courage of the Sharps and the Fry group in France cannot be denied or understated.

Were they, as Yad Vashem designated, Righteous Among the Nations? What are the standards and values associated with the designation?

“The definition of the Righteous was set down in the law establishing Yad Vashem as non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. Thus, the title is not intended for all those who helped Jews or contributed to their rescue, but to a smaller circle. In order for someone to be recognized, there needs to be an additional element - the element of risk. Having said that it should be noted that there is no attempt on our part to diminish the value of the moral stand and of the humanity of those who helped Jews and do not fall within the criteria established by the Commission that designates the titles. We are faced with a number of cases of people who showed moral courage and were extremely compassionate towards the Jews, but were not awarded the title because their actions do not fall within the definition.

Since most diplomats did not risk their lives, the Commission decided that in such cases it would also consider awarding the title in cases when diplomats risked their position, i.e. if they acted against their instructions or their country's policy. Some of the diplomats that were recognized as Righteous were fired or severely reprimanded by their governments, etc.

The Bingham file was very carefully examined by the Commission. After reviewing the entire documentation, the Commission decided not to recognize him as a Righteous because no proof was found that he had acted against his government's instructions that he gave visas against regulations, that he broke the law or that he had to pay a price because of his positive conduct. However, in view of his very sympathetic attitude and treatment of the Jews - the commission expressed its appreciation and gratitude to his family.

Regarding Mary Jane Gold, it is indeed established that she was involved in helping refugees, but so far we have no documentation (primary sources, not articles or books) showing that her assistance involved risks, and we are therefore unable, as for now, to submit this case to the Commission for the Designation of the Righteous.” (Yad Vashem response as to why Hiram Bingham was not designated as Righteous Among the Nations.)

The question was further clarified by Yad Vashem:

“Jerry,

The question you ask touches on a very important and complex element in the Commission's criteria. The answer therefore is yes and no. Let me try to explain: Since the title is awarded to those who knowingly decided to take responsibility for the rescue of Jews, what counts is whether the rescuer was consciously and intentionally saving Jews. A family that was hiding Jews will be recognized, even if they also helped others (people who evaded forced labor or downed allied pilots, etc.), on condition that they were aware that they were hiding Jews (and that the other conditions are in place). This will be because they knowingly took Jews into their home to rescue them. If, on the other hand, there is no proof that the person was aware of the identity of the people he helped or if we are dealing with a network where one link in the chain helps all those that are sent his way - Jews and non-Jews alike - the Commission may decide that there was no proof that the candidate is entitled to receive the title.

Regards,”(Respondent’s name redacted)

Recognition of Righteous Among the Nations is not taken lightly by Yad Vashem. It is a very serious matter of intense review by volunteer committee members representing the most serious legal and moral council in Israel.

The question of the universality of saving life, whom to save and why, is not a comfortably settled issue in Jewish thought.

From a simple but thorny question:

“Dear Rabbi,

A Judaic life and law question:

You are a Jewish physician. There is a terrible deadly disease. You have two very ill patients. They are children. One of the children is Jewish the other is not, otherwise their situation and prognosis is identical.

Which child should get the medicine? What does Jewish law say?” From Rabbinic questions and answers:

“I know this is a real world question - but today I would hope we could treat both children.

In a secular triage ethic if that is the case where we only have resources to treat one - we would treat the one with the best chance of full recovery.

I am uncomfortable applying the Mishnah below from Masechet Horayot Chapter 3 [but it clearly sets a priority on Jews]:

A man takes precedence over a woman in matters concerning the saving of life and the restoration of lost property, and a woman takes precedence over a man in respect of clothing and ransom from captivity. When both are exposed to degradation in their captivity the man takes precedence over the woman. A priest takes precedence over a levite, a levite over an israelite, an israelite over a mamzer, a mamzer over a natin, a natin over a convert, and a convert over a freed slave. When is this so? When all these were in other respects equal. However, if the mamzer was a scholar and the high priest an ignoramus, the scholar mamzer takes precedence over the ignorant high priest.

Jewish law does set up a hierarchy for saving life. But the last phrase seems to establish a merit criteria rather than a genetic one.

Explanation (from USCJ Mishnah Yomit from December 2003)

Our mishnah is clearly chauvinistic, and we should acknowledge it as such. As I have stated before when such types of mishnayoth have appeared, while I can understand the mishnah as reflecting common societal values in the ancient world, I cannot internalize the mishnah as reflecting my own values.

Nor do I believe that any Jew reading this mishnah should do so.

The mishnah states that if one has the opportunity to save the life of a man or a woman, but only one of them, the man takes precedence. Similarly, if one has the opportunity to restore lost property to either a man or a woman, he should return that which belongs to the man. For instance if he finds two lost horses, one that he knows belongs to Jacob and one to Rachel, but can only return one, he should return that which belongs to Jacob. However, when it comes to issues of potential degradation, the woman's modesty comes first. If one has only enough money to help buy clothing for a man or woman, the woman takes precedence. This is because it is more embarrassing for a woman to be poorly clothed than for a man. Similarly, if one has only enough money to redeem one captive, one should redeem the woman, lest she be raped during captivity. Men are not usually raped during captivity. We know that this is the reason that women are redeemed first, because the end of the mishnah states that if there is concern that the man might be raped, he is to be redeemed first. According to the mishnah, it is worse for the man to be raped than for the woman.

According to commentaries, this mishnah deals with precedence in any matter of honor or profit. The mishnah considers certain genealogical lines of Jews to be inherently more holy than others. A priest is holier than a levite and a levite is holier than an Israelite. A mamzer is someone who was born of an illicit sexual union of two Jews, therefore an israelite takes precedence over a mamzer. A natin is a descendent of the Gibeonites who converted during the time of Joshua (see above 1:4). Since a mamzer does not have any foreign descent, he is holier than a natin. A natin is holier than a current convert, because a natin was part of Israel from before his birth, whereas a convert has only just now converted. A convert is holier than a freed slave for a convert was never part of such a lowly occupation.

Up until now the mishnah has stated what must be considered something similar to a genealogical caste system. Each person is born into a certain status, and these separate statuses are ranked. We might think that at least during a person's lifetime, he could not move up or down in status. The last clause of the mishnah radically undercuts that ideology. While in theory a person's "holiness" is attributed to birth, a person's true holiness is attained through the study of Torah. A mamzer who studies Torah is higher than a high priest who does not, even though the latter has the highest pedigree of genealogical status. In practice, this will become the only criteria for "ranking" individuals, for no two individuals will be exactly the same in their Torah learning.

This statement in essence is one of the supreme value statements for the entire Mishnah. The rabbinic social system was a meritocracy, where one merited one's position based on commitment to Torah study, and not based on one's filial connections.”

From the question the issue of the Fry group and the Sharp’s efforts flowed. Does the question over saving life permit choice?

“Is a Jew required to risk his life to save a strangers life if he knows it will endanger the lives of his family and his community? The answers I have found so far have not been very satisfying, especially Rabbi Akiva's from the Talmud. The risk is not to the individual who jumps into the water to save the stranger or the issue of sharing or not sharing the last bit of water but what happens to those behind? Can we make decisions of life and death based upon our own code of religious morality if it affects other people's lives? Rabbinic response: “If a building collapses on a person [on the Sabbath]…they [may] dig to remove the rubble from him [to try to save his life]…but if he is dead, they leave him there [until after the Sabbath because it is forbidden to dig on the Sabbath]. How far does one check [to determine whether or not he is dead]? Until his nostrils; and some say, until his heart” (Tractate Yoma 85a).

The individual whose life is to be saved must be a specific, identifiable individual, rather than an abstract or potential beneficiary.

The laws of pikuach nefesh apply equally in saving the lives of a Jew or a Gentile, since a Gentile is just as much God's creation as a Jew. If one must choose between saving a Jew or a Gentile, and can only save one, the one who is more likely to survive given the circumstances must be saved.

Pikuach nefesh does not apply when an animal's life is in danger, and halakha may not be broken to save the life of an animal.

Another question is what constitutes a life-threatening situation. Some situations are clearly life-threatening, such as one who is dying of a disease and will die without medical intervention, or one who is drowning and will not be able to escape the water without help from another. But in other situations, it may be unclear if a life is truly in danger.

2) Daniel Eisenberg, M.D.

How should society balance long-term medical research, versus more immediate needs?

While an individual physician is rarely permitted to withhold resources from a dying patient to ameliorate future need, society may have a different set of ethical standards. May we take future societal needs into account?

Jewish law recognizes society's legitimate future communal needs. The Talmud (Nedarim 81a) describes a scenario in which two cities share a water supply that originates with the community on the top of a hill. The Talmud rules that the upstream community takes precedence if there is only enough water to provide drinking water to one community, because the water "belongs" to the upstream community.

This decision is in full accord with the famous opinion of Rabbi Akiva that if two men are lost in a desert with one flask of water, the owner of the flask may drink it at the expense of his friend's life. No one is required to give up his or her life to save another.

But what if the upstream community wants to use the water to bathe and wash clothes, and the result will be a shortage of drinking water for the downstream community? In this case, the Talmud has a disagreement. While the majority opinion forbids the first city to hoard water for bathing and washing clothes if the second city will lack drinking water, there is an opinion of Rabbi Yossi that permits the upstream city to keep the water at the expense of the downstream community.

What possible rationale could there be for depriving a city of drinking water so that others may wash clothes? The opinion makes sense when we understand that Rabbi Yossi accepts the opinion of a physician-rabbi in the Talmud who felt that abstaining from bathing and washing clothes could result in the development of life-threatening illnesses. Therefore, according to this opinion, one may put the second city's welfare in present danger -- in order to save the first city from a grave future danger.

RESOURCE ALLOCATION

Rabbi Yossi's opinion also fits with a fundamental Jewish principle regarding an individual's obligation to risk his life in order to save another. Do I have to jump into a river to save someone who will definitely drown? It depends on how well I swim! That is, my obligation to save the life of another depends on the certainty of death to the other person and the degree of risk to me. If the river is slow moving and I am an excellent swimmer, then surely I should jump in. But if the river is fast moving and I cannot swim, then I am forbidden to jump in according to most opinions.

The principle is that while I may not sacrifice my own life in order to save someone else's, I am also enjoined from killing someone else to save myself. Therefore, I can justify using my own resources to save myself at the expense of another, but not taking his resources to save myself. A gravely ill patient does not have to, nor is he usually permitted, to voluntarily give up his private stock of life-saving medicine to save someone else.

What is the value of life? What is the mandate of Jewish law about the value of life? The picture is complicated, uncomfortable and becomes extraordinarily convoluted. Live Organ Donations - Part 1 of 1

by Rabbi Chaim Jachter

Introduction

The overwhelming majority of Poskim (Halachic authorities) oppose transplants of hearts, livers, and lungs from a cadaver since they do not accept “brain death” as a legitimate definition of death, as explained in an essay archived at www.koltorah.org. However, Halachah encourages donation of certain organs from a live donor, as we shall outline in this essay. Our discussion we will based on a great extent on the writings of Rav Asher Bush, chairman of the Rabbinical Council of America’ Halachah Commission.

The Obligation to Rescue

The Torah commands us “Not to stand aside while your fellow’s blood is shed” (VaYikra 19:16). The Gemara (Sanhedrin 73a) clarifies that this Pasuk obligates us to expend all efforts and financial resources to save another human. Rashi (ad. loc. s.v. Ka Mashma Lan) explains the phrase “do not stand” as meaning “do not stand on yourself; rather, exhaust all possibilities in order that your fellow’s blood not be lost.” The Gemara and Rashi, however, do not state whether the efforts required in saving another’s life include an obligation to risk one’s own life.

Risking one’s Life to Save Another

The Beit Yosef (Choshen Mishpat 426 s.v. UMah SheKatav BeSheim HaRambam) cites the Jerusalem Talmud (Terumot 8:4), which requires us to endanger our lives to save another from certain death. The Jerusalem Talmud (Yerushalmi) reasons that the fellow’s certain death overrides rescuer’s possible death. The Gemara (Pesachim 25b and Rashi ad. loc. s.v. Mai Chazit) states that all life is equal, with its celebrated phrase “how does one know that his blood is redder than his friend’s.” However, the Yerushalmi believes that the blood of one in certain danger is redder than the one whose life is only possibly in danger.

However, the Sema (a major commentary to Choshen Mishpat) notes that Rav Yosef Karo (the author of both the Beit Yosef and the Shulchan Aruch) does not cite this ruling of the Jerusalem Talmud in the Shulchan Aruch (C.M. 426). The Sema (426:2) explains that the fact that Rif, Rambam and Rosh do not cite the Jerusalem Talmud’s ruling convinced Rav Yosef Karo that it is not accepted as normative Halachah.

The rulings of the Jerusalem Talmud are authoritative unless contradicted by the Babylonian Talmud (Talmud Bavli). Accordingly, the Rif, Rambam and Rosh must believe that the Bavli rejects this ruling of the Jerusalem Talmud, as noted by the Agudat Eizov (cited in the Pitchei Teshuvah C.M. 426:2). Acharonim scour the Bavli for evidence that it rejects this ruling and cite a variety of sources (summarized in Teshuvot Tzitz Eliezer 9:45).

The Netziv (HaEimek She’eilah Parashat Re’eih) and Maharam Schick (Teshuvot Y.D. number 155) cite a well-known passage (Bava Metzia 62a) as evidence that the Bavli rejects the Yerushalmi’s ruling. The Bavli presents a case in which two people are walking in a desert and one of them holds a pitcher of water in which there is sufficient water for only one of the two individuals to survive. Ben Petura rules “better that the two of them die and one should not see the death of his fellow.” Rabi Akiva, though, argues that the one holding the water should drink since “one’s own life enjoys priority over his friend’s life.” The Gemara notes that while Ben Petura’s position was originally the accepted one, Rabi Akiva’s ruling was later accepted as normative.

The Netziv and Maharam Schick argue that Ben Petura does not advocate an unreasonable opinion of requiring a needless death. Rather, he calls for the sharing of the water which does not involve certain death; rather, it involves risking one’s life in order to save another from certain death. Even if one believes that there is insufficient water for both to be able to reach a water source, there is a reasonable possibility that one may unexpectedly encounter an oasis, spring or caravan willing to share its water. Rabi Akiva, though, rules that one is not obligated to risk one’s life in order to save another’s life.

According to this interpretation, Ben Petura advocates the Yerushalmi’s approach. Thus, since the Bavli concludes in favor of Rabi Akiva, normative Halachah does not require one to sacrifice his life in order to save another’s life. Indeed, the Mishnah Berurah (329:19) and Aruch HaShulchan (C.M. 426:4) rule that one is not required to risk his life to save another.

They caution, however, that one is forbidden from overzealously guarding his own life by ignoring the plight of one whose life is in danger. Rav Asher Bush, offering an example of a lifeguard rescuing someone from drowning, states, “For a qualified lifeguard there is certainly a risk to jump into a pool to save a drowning swimmer, but it would be more than difficult to suggest that he is not obligated to do so, as common sense does not group this with ‘dangerous activities.’” He argues that “those activities whose statistical risks are negligible to the point that they are not thought of as risky, are precisely the activities that the Torah has obligated even though there may be some slight risks.”

Sacrificing a Limb to Save another’s Life

In the difficult history of our people, we have been faced with unspeakable situations. One such circumstance was where a government official threatened to kill a Jew if his fellow Jew did not permit him to remove a limb. Poskim were asked whether the Halachah requires the sacrifice of a limb in order to save a life. Radbaz (Teshuvot number 627) rules that one is not obligated to sacrifice a limb even if it entails the death of another Jew.

Radbaz writes that the Torah is by definition “pleasant and peaceful” “Deracheihah Darchei Noam VeChol Netivoteha Shalom,” Mishlei 3:17) and would not compel a person to sacrifice a limb. However, one who sacrifices a limb to save another’s life fulfills a great Mitzvah, as long as it does not involve a fifty percent or higher risk of death. Our bodies belong to Hashem and we have no right to place our lives at such great risk.

Poskim have, generally speaking, accepted this ruling of Radbaz and do not require the sacrifice of a limb even if there is no significant risk involved. The Shach (Yoreh Deiah 157:3) apparently supports this ruling (as he does not require sacrificing a limb to avoid violating any Torah law that does not require one to sacrifice his life) and the Pitchei Teshuvah (157:15) cites Radbaz and does not present a dissenting view. Rav Moshe Feinstein (Teshuvot Igrot Moshe Y.D. 2:174:4) and Rav Eliezer Waldenberg (Teshuvot Tzitz Eliezer ad. loc.) accept this ruling of Radbaz.

Live Kidney Donations

Dayan Weisz (Teshuvot Minchat Yitzchak 6:103) in 1961 ruled that it was forbidden to donate a kidney due to the significant risk of death involved in the procedure and due to concern for future need of the donated kidney. However, in an undated Teshuvah (written after 1961 but before 1980; it seems to have been written during the 1970’s) Rav Eliezer Waldenberg (Teshuvot Tzitz Eliezer 9:45) while initially agreeing with Dayan Weisz, proceeds to modify his stance and considers permitting a live kidney donation if “a team of specialists decides after a rigorous examination that the donation does not involve risk to the donor.” He concludes, nonetheless, “Kuli Hai VeUlai,” even after all efforts are exerted, the doubt remains unresolved.

Rav Ovadia Yosef, however, writes in a Teshuvah published in 1980 (ad. loc.) that Torah observant specialists have informed him that the risk involved in kidney donation is very slight and that ninety nine percent of donors return to full health. Based on this information, Rav Ovadia Yosef rules “it is certainly a Mitzvah to donate [a kidney] to save his fellow from certain death.” We should note that Rav Yosef does not state that it is an obligatory to make such a donation. This seems due to the ruling of the aforementioned Radbaz that the Torah does not oblige one to give up a limb even in order to save another’s life.

Live Liver Donations, Blood and Platelets Donations and Bone Marrow Donations

Rav Bush notes that live liver donations are permitted and but not required by Halachah due to the considerations presented above. Although the risk involved in live liver donation is somewhat higher than live kidney donation (and is performed less frequently), Rav Bush writes that a relatively small percentage does not rise to the level of activities that are deemed too dangerous even to save another from certain death.

By contrast, since blood and platelets regenerate in a relatively short time and there is no significant danger involved, Rav J. David Bleich and Rav Mordechai Willig rule that one is obligated to donate blood and platelets if there is a dangerously ill individual currently is in need.

Bone marrow donation is safe and is performed, like other cases of live organ donations, only in cases where there is a dangerously ill individual currently in need. However, removal of the marrow is painful and often requires general anesthesia. Rav Bleich and Rav Willig rule that since the risk of general anesthesia is so minimal, one is obligated to make such donation even if there will be somewhere residual pain and lost work time. We noted earlier that the Gemara requires one to expend every effort to save his fellow’s life. We should note, however, that Rama (Y.D. 252:12) and Shach (C.M. 426:1) rule that the beneficiary must compensate the donor, if possible, for the financial loss sustained in saving his life.

Conclusion

Orthodox Jews are criticized in some circles for not donating certain organs after death. We may respond that the overwhelming majority of Halachic authorities regard such donations to be forbidden and unethical. Orthodox Jews also strongly consider donating live organs such as kidneys and livers, especially since most do not approve of most post-mortem donations. Organizations such as the Orthodox Union and Agudath Israel should even consider lobbying for tax breaks for such donors. We should also be at the forefront of blood, platelet and bone marrow donation. This would be a most effective response to our critics.

The Rabbinic answers received almost universally contained clauses of not being comfortable with the answers and the need to consult even greater scholars.

How would anyone respond normally to the threat of saving a life if one’s own life or that of their family would be put at risk?

Within the narrower definition of Yad Vashem, Varian Fry and the Sharps knew that Jewish lives would be saved. They knew that by deliberately saving Jewish lives they were placing themselves in greater risk than if they had saved non-Jewish lives. They knew the consequences and were willing to make the difficult decision.

Then the LORD said to Cain, "Where is your brother Abel?" "I don't know," he replied. "Am I my brother's keeper?" Genesis 4:9

Jerry Klinger is President of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, www.Jashp.org email: Jashp1@msn.com

~~~~~~~

from the April 2010 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|