| |

May 2014 |

|

| Browse our

|

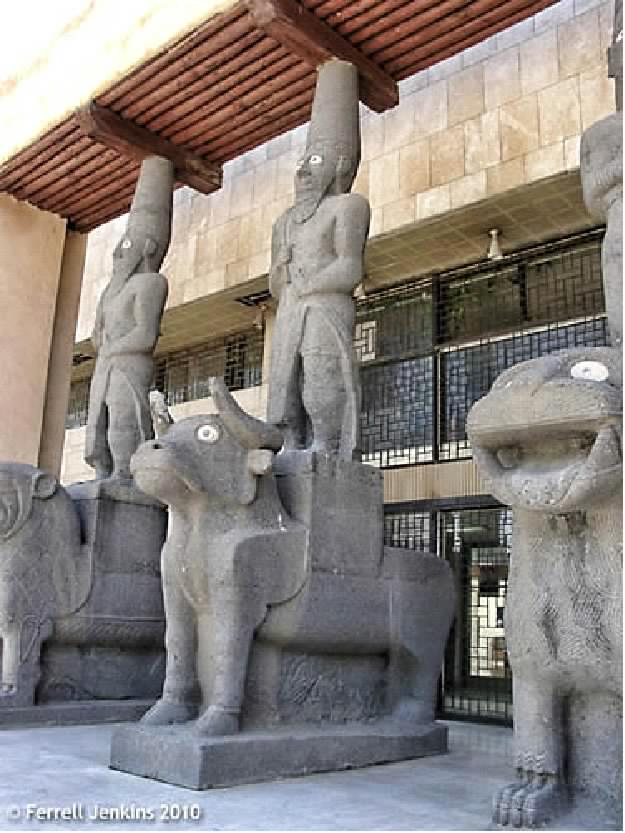

Bull Symbolism in the Golden Calf Narrative By Murray J. Mizrachi The text of Genesis tells us that Aaron exclaims in reference to the infamous golden calf, This is thy god, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt.'(Exodus 32:4) How is it possible that the nation who witnessed the exodus and the law giving at Sinai could stoop so low as to worship the golden calf? Many of the commentators both contemporary and ancient such as the Meir Tob (2001) and Don Isaac Abrabanel (14371508) remark that the Israelites were certainly not stupid or crazy, so why would they believe such a statement, how could they? The juxtaposition of the first commandment explicitly prohibiting idolatry further exasperates the point. I am the LORD thy God, who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt have no other gods before Me (Exodus 20:2). Psalms, scornfully rebukes the people on their idolatrous folly. The Psalmist mocks the people for trading the true God for a corporal being that feeds on hay: Thus they exchanged their glory for the likeness of an ox that eateth grass (Psalms 106). Is there perhaps a deeper symbolism behind the golden calf that caused the Israelites to stray? Rashi, Targum, the Talmud, Midrash and R Obadyah Seforno (1475-1550) take a literal approach and felt that the Israelites worshipped the golden calf as an deity. Many of the commentators are bothered by this leap to deification. R Isaac Samuel Reggio (1784-1855) in his commentary on Exodus reminds his readers that this calf was made from the peoples jewelry, so to think that their donation became divine is absurd. R Saadia Gaon, R Yehudah ha-Levi, Rambam, Ramban, Ibn Ezra, Don Isaac Abrabanel and R Samuel David Luzzato felt the incident was a pseudo-idolatry known in Hebrew as a masecha in which God was worshipped through the medium of the golden calf. This latter camp of scholars points to the language of the text in Genesis 32 which calls the actual calf a masecha and the subsequent party that Aaron claimed was for God specifically, and not to any other deity as the verse itself emphasizes a feast to the LORD.'(Exodus 32:5) The golden calf episode is repeated again in a lesser known incident in I Kings 12:28 : Whereupon the king [Yarobaam] took counsel, and made two calves of gold; and he said unto them: 'Ye have gone up long enough to Jerusalem; behold thy gods, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt. Here, again not one but now two golden calves are set up and proclaimed the gods responsible for taking the Israelite tribes out of Egypt. This story is remarkably similar to the story in Exodus, and again begs the question, why did the people take to so readily to the bull imagery? Surely the newly freed slaves were aware that man-made golden bulls were not responsible for the exodus. What is clear is that both episodes were not part of the monotheistic covenant. Other domesticated animals must have held religious stature in ancient society. Even animals such as goats were worshipped. Leviticus 17:7 states And they shall no more sacrifice their sacrifices unto the goats (Seeirm) that you chase after. In pagan societies Saytrs and the constellation Aries were commonly worshipped. The Bull however was the largest domesticated animal with the greatest physical strength and therefore the most revered in ancient civilization. Even today the bullfighter is considered courageous for standing up to the most ferocious of beasts while being cheered on by thousands. The expression of a brave person taking the bull by the horns is widely understood throughout the world and in several languages. The Astrological Taurus is an idolatry vestige still prevalent in modern popular culture that also glorifies the bull. Present Hindu culture similarly deifies bulls as a source of sustenance, virility and strength. Bull Symbolism in the Bible The strength of the Bull (Proverbs 14:4) is stressed numerous times throughout the scriptures. Strong individuals are associated with bulls such as Simeon and Levi who Jacob curses in their anger they slew men, and in their self-will they houghed oxen. (Genesis 49:6). In Deuteronomy we find Moses giving a blessing of power and virility to Joseph His firstling bullock, majesty is his; and his horns are the horns of the wild-ox; with them he shall gore the peoples all of them, even the ends of the earth; and they are the ten thousands of Ephraim, and they are the thousands of Manasseh (Deuteronomy 33:17). Later in Psalms the psalmist uses the imagery of bulls to depict powerful enemies that have come to harm him Many bulls have encompassed me; strong bulls of Bashan have beset me round (Psalms 22:13). In the famous Psalm 92, recited every Sabbath by practicing Jews the psalmist is saved by God the imagery of the bull is depicted once again: But my horn hast Thou exalted like the horn of the wild-ox; I am anointed with rich oil (ibid 92:10). Most striking is a reference to bulls in Numbers where God himself is compared to an ox by Balaam : God who brought them forth out of Egypt is for them like the lofty horns of the wild-ox (Numbers 23:22). One chapter later during the same narrative Balaam conjures the symbolism of the bull once more: God who brought him forth out of Egypt is for him like the lofty horns of the wild-ox; he shall eat up the nations that are his adversaries, and shall break their bones in pieces, and pierce them through with his arrows. He couched, he lay down as a lion, and as a lioness; who shall rouse him up? Blessed be every one that blesseth thee, and cursed be every one that curseth thee (Numbers 24:8-9). Here the association of the bull is with strength capable of destruction, comparing God/bull to a lion, the most powerful wild animal. In perhaps a more familiar context every Friday night in Jewish services the power of a bull, specifically an egel (young bull) in comparison to Gods power is depicted: He maketh them also to skip like a calf; Lebanon and Sirion like a young wild-ox (Psalms 29:6). Finally the cryptic vision of the chariot in the book of Ezekiel once more includes the image of a bull: As for the likeness of their faces, they had the face of a man; and they four had the face of a lion on the right side; and they four had the face of an ox on the left side; they four had also the face of an eagle. The book of Ezekiel as in Numbers the reader finds the bull compared to the most powerful of beasts: the lion and eagle. Later in the rabbinic mystical traditions the bull came to symbolize the Kabalistic concepts of Geburah and Yesod. Bull Symbolism in the Ancient World Through a perusal of archaeological and extra-biblical sources we find that bulls were held in the highest regard throughout the ancient world. Images of calves/ bulls have been found everywhere from India to Rome. The ancient Greeks often personified Zeus, their chief deity in the form of a bull. Many mythological tales tell of Zeus who trans-mutates into a bull form and impregnates young human females (as in the abduction of Europa). In classical Greece offenders were thrown into the brass Sicilian Bull to roast offenders in a cruel form of public execution. Closer to Ancient Israel the Canaanite god Baal was also personified as a Bull, as was the Assyrian chief deity Hadad. Pictured below is a statue of the Assyrian god Hadad riding a bull in the History of Syria Museum in Aleppo.

In other instances from the ancient world statues of winged bulls with human heads were carved into the facades of temples and palaces to symbolically guard the entranceways. Examples of this type of architecture are found in any major museum with a near-eastern collection throughout world. Below is a famous example from the Persian palace of Cyrus the Great now found in the Louvre.

Perhaps the civilization with the most reverence for the bull was none other than the Egyptian Empire of which the young nation had just left. R Eliyahu ben Amozeg (1833-1900) in his Exodus commentary cites the prominence of the Apis Bull in the Egyptian idolatry canon. This Egyptian bull worship sounds very similar to the concept portrayed by many of the traditional commentators who stressed that the golden calf was a masechah. The Apis was an extremely rare genetic variation of a bull with unique markings that had to be identified and confirmed by Egyptian cult priests. Egypt viewed this bull as the physical manifestation of the Egyptian chief god Osiris on earth. If the bull moved left as opposed to right or took seven steps instead of eight, the priest would declare this significant prophecy. Once the Egyptian priest established the bull as an Apis a great celebration ensued. The Apis bull was moved to a temple where it was well fed, patronized with a harem of cows and visited by pilgrims. During holiday times, the bull was adorned with flowers and jewels and paraded through the street to be worshipped by all. Even after death the Apis was mummified and consecrated to elaborate tombs. Although ridiculous, to a modern western society- this was the civilization that the young monotheistic nation was surrounded by in ancient Egypt. View of Maimonides Maimonides (as quoted by his son R Abraham) finds it more than a coincidence that the Exodus narrative occurred historically during the astrological constellation Taurus (April 20 - May 20). R Saadia refines the point claiming that when the people saw that Moses delayed to come down from the mount (Exodus 32:2) it was assumed that Moses died, and therefore a new medium was necessary to aid in religious observance. The most obvious choice for the people would be the idolatry they were accustomed to in Egypt. In light of world attitude of bovine at the time, the picture becomes clearer. Here was a new nation struggling to divorce itself from its Egyptian/ idolatrous ways. The Bible recognizes this resistance and in fact takes extraordinary measures to counteract the Egyptian influence on the new Israelite nation. Leviticus explicitly prohibits Egyptian practices and worship After the doings of the land of Egypt, wherein ye dwelt, shall ye not do; (Leviticus 18:3). Maimonides even considered it a sin to return and live in Egypt physically. Maimonides writes that it was the intention of the ritual laws know as huqqim to separate the new nation into a distinct monotheistic culture by counteracting the influence of the prevalent idolatry of the time. He writes in his Guide (3:48-39) that he was limited in his understanding of ancient idolatry, due to a lack of ancient sources available to him, but insisted that many of the huqqim share an unknown idolatry connection. The scapegoat and red heifer show a symbolic antithesis to the idolatry practices of Egypt and fit much with Maimonides explanation of the role of huqqim. The Apis Bull mentioned above was so revered that the ground that this bull stepped on was literally worshipped by ancient Egypt. It is highly significant that Jewish law also appoints a priest to seek out and confirm the rarest of bovine in its own tradition - with the red heifer. In contrast to the animists of Egypt, the Jewish priest must remove the beast from the temple grounds and burn the animal until it is reduced to ashes. This seems to directly foil the holiday parade and enshrining of the mummified remains of the Egyptian Apis cult worship. In fact all parties including the priest who participated in the red heifer ceremony were considered ritually unclean (tameh) and not allowed into the holy camp of Israel. In a similar fashion the scapegoat was thrown off a cliff. Although there are still many questions revolving around the golden calf incident of Exodus, it seems that the whole episode reflects the monotheistic struggle to separate from pagan culture. The golden calf was an attempt to fill the void of an abstract God with a familiar Egyptian symbol. Send comments to: Murraymiz@aol.com Selected Bibliography: Benamozegh, Elijah . Em la-Mikra. 1st edition. Leghorn : 1862. Print. ben Moses ben Maimon, Abraham. Commentary on Exodus. London: 1958. Print. Yedid ha-Levi, Yom-Tob. Commentary on Exodus. 1st edition. New York: Keren Yom Tov, 2001. Print. Reggio, Isaac Samuel . Sefer Torat Elohim. 1st edition. Leghorn: 1821. Print. from the May 2014 Edition of the Jewish Magazine Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used. |

|

| All opinions expressed in all Jewish Magazine articles are those of the authors. The author accepts responsible for all copyright infrigments. |