| |

October 2014 |

|

| Browse our

|

The Golden Rock to the Golden Door By J. Klinger Of the many islands in the Caribbean, St. Eustatius is one of the smallest. It may be small but the island played an enormous role in the success of the American Revolution. The Jews of St. Eustatius were central to that success but not for the reasons you would have expected.

St. Eustatius, or Statia, as the locals call it, lies about 60 miles to the S.E. of St. Martin. It is a gentle 18 minute flight aboard a Win Airlines prop to F.D. Roosevelt Airport. The Island is roughly eight square miles in size and crowned with a dormant volcano the Islanders call the Quill. Administratively, Statia is part of a confederation with Bonaire and Saba. Together, they are known as the BES Islands. They are a special municipality of the Netherlands. The capital is Oranjestadt. Dutch and English are the languages of this friendly Island where diving, tourism and history meld into one gentle, uncrowded experience. Christopher Columbus, in 1493, saw Statia from a distance. Straining to see what appeared to him as snow on the top of the volcano in the balmy warmth of the seas, he named the Island for what he wanted to see, not what was. Columbus named the Island, Santa Maria del la Niebe (St. Mary of the Snow). The name did not stick. In 1636, eighty Dutch families from the Netherlands settled on the Island, renamed St. Eustatius. The Island was an excellent choice with its large natural harbor. The colonists prospered, successfully planting tobacco and later cotton. Success and prosperity did not equate to peace in the turbulent Caribbean where pirates and European powers contested for wealth and power. In the nearly 375 years of Statias modern history, the Island has changed hands 22 times after having been pillaged, attacked, ravaged and reborn, again and again. Agriculture, though important, was not to be the ultimate driving power of Statias economic prosperity. It was commerce. Open commerce made Statia wealthy. Its port became the center of Caribbean duty free commerce in the 1750s. Thousands of ships called at Statias harbor annually. Hundreds and hundreds of warehouses crammed with trading goods lined the shore below the walls of Ft. Oranje. The Island was nicknamed the Golden Rock with good reason. The Dutch understood the importance of an open society and commercial success. Their society welcomed all who could enhance Holland and its commercial interests. That understanding included Jews. Many years after the Dutch had opened their doors to the Jews, Edmund Burke summarized their importance to world commerce in an address to the British Parliament, the Jews the links of communication, the mercantile chain the conductors by which credit was transmitted through the world Columbus sailed the Ocean Blue in 1492. As Columbus sailed the Ocean Blue in 1492, the Spanish Jews searched for a land that they could find refuge in. 1492; the Spanish exiled any Jew within their borders who would not convert to Catholicism. Portugal did the same, five years later, in 1497. Holland, and its Caribbean possessions, was much more tolerant of Jews. Holland welcomed them. Holland prospered. Jews were first mentioned on St. Eustatius in 1660 when Abraham Israel Henriquez met with David Saraiva on St. Eustatius to consider how to transport horses to the Island. The Jewish population of Statia grew slowly, despite the repeated attacks of French Pirates. By 1722, out of a population of 524 free inhabitants, sadly slavery was part of Statias history, there were 22 Jews. Anti-Semitism on French and English Islands were inducements for Jewish settlement to Statia. Jews were considered stateless, a wandering people, a Nation, as the Spanish/Portuguese Jews called themselves, with no legal rights. Holland did not emancipate Jews living within their borders until 1834 and Britain, even later, 1858. Until emancipation, their welcome always could be tentative. The Statia Jews appealed to their brethren in Holland who were leaders of the Dutch Jewish community and significant shareholders in the Dutch West Indies Company. The Dutch West India Company controlled the far flung Caribbean Islands, including Statia. The Company wrote to the Commander of St. Eustatius, Everard Raecx, September 18, 1730. The Jewish merchants on St. Eustatius were to have the same commercial rights as Christians had. Jewish religious observances were to be tolerated. Seven years later, 1737, the Jews of Statia had grown large enough to build a magnificent synagogue, Honen Dalim, She who is Charitable to the Poor, in the capital city of Oranjestadt. Permission for building again came from the Dutch West India Company, with significant funding support from the Jewish community on Curacao. Permission was conditioned that the Jewish house of worship would be sited where the exercise of their (Jewish) religious duties would not molest those of the Gentiles. Honen Dalim was built within sight of the large Dutch Reformed Church and the walls of Ft. Orange. It was built off of a small, narrow lane called Synagogue Path.

Earlier, a separate Jewish cemetery had been created at the top of the city, next to the municipal cemetery. The earliest Jewish burial sites that are still visible date from 1720. The Jewish cemetery stones include markers that are made of imported marble, ornately carved and written in Hebrew, English and Portuguese. They attest to the wealth and international associations of Jewish commerce and community. Extensive Jewish commercial connections, from St. Eustatius, interlaced throughout the Caribbean to Europe and the Americas. The cemetery is, respectfully, well cared for today.

Commerce by the 1750s was the lifeblood of St. Eustatius. Jews were estimated to have made up more than ten percent of the permanent population of the Island. The vast majority of the Jews of Statia were involved in commerce as the American Revolution became a reality. Yet, they were a far more disproportional influence in the commercial life of Statia than their numbers represented. During 1776, eighteen ships from Statia, ran the British blockage and reached rebel ports in North America. The British were furious. They were even more enraged when a small American Brig, the Andrew Doria, flying the young governments flag, arrived in Statias harbor, November 16, 1776. She was looking to buy gun powder and military supplies for the Continental army. Captain Isaiah Robinson, of the Andrew Doria, fired a thirteen gun salute, one for each Colony, announcing the arrival of the ship under the strange new flag, the Grand Union Flag. Governor Johannes de Graff ordered an eleven gun, protocol correct, reply. It was the salute heard around the world. It was the first international recognition of the struggling new American government in the former British colonies.

The Andrew Doria carried a precious cargo to Governor De Graaf of St. Eustatius a copy of the Declaration of Independence. The British had captured an earlier copy being sent to Holland. It was found wrapped with writings in a strange cipher they did not understand Yiddish. Until 1777, the British did not understand how so many munitions were arriving in rebel ports. A captured ships documents in Maryland pointed to the answer. Huge amounts of munitions were being transshipped from St. Eustatius. The Island and the Jewish merchants, true, were making enormous fortunes supplying the Revolutionary forces. They had converted St. Eustatius into a vast military supply depot for the American Revolution. Half of all American war supplies would eventually go through Statia. The British knew that this could not be tolerated. Holland was neutral. St. Eustatius, being Dutch, could not be attacked by the British. Late in 1780, December 20, Britain Declared War on Holland. Even before the Declaration of War, Britain had assembled a mighty battle fleet to destroy St. Eustatius and then to aid Cornwallis and the British in North America.

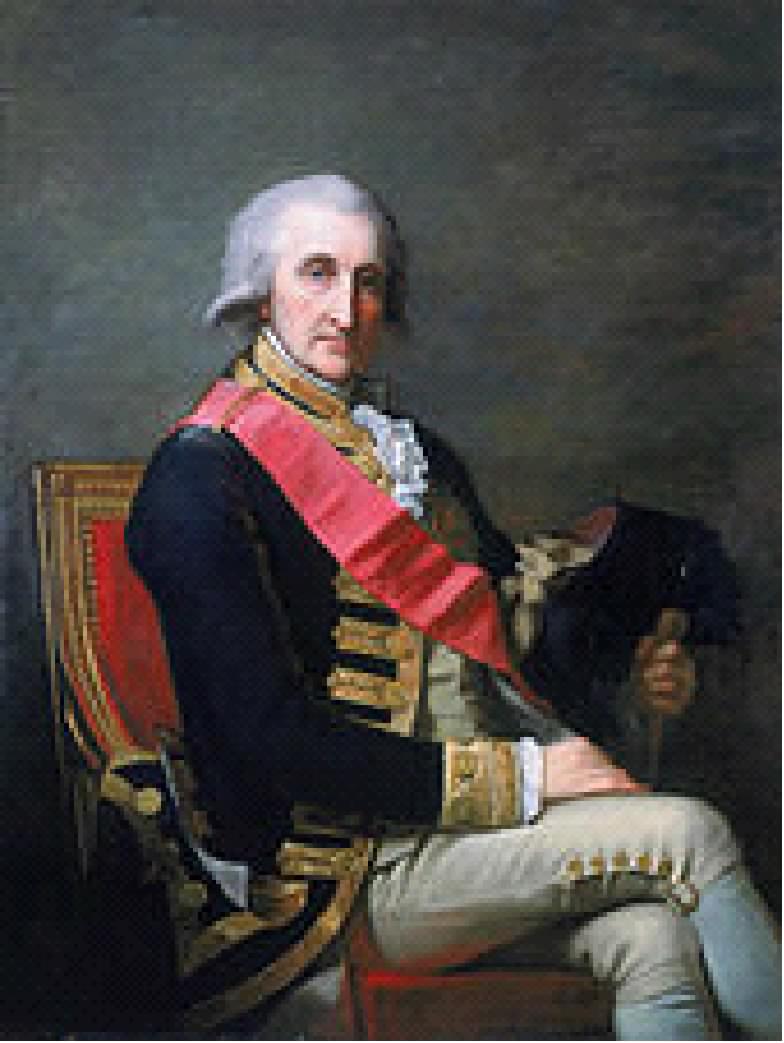

Admiral Rodney February 7, 1781, fifteen British Ships of the Line, over 1,000 guns, followed by support ships, five frigates and smaller craft transporting 3,000 ground troops, sailed into St. Eustatius harbor. The entire Dutch garrison of Ft. Oranje, 61 men, surrendered. The British under the command of Admiral Sir George Rodney captured the Island. He captured almost 200 ships in the port, the stores along the water front and the population. The British destroyed Statia in 1781. Rodney destroyed Statia not just for the Gold, but because of what and who were on the Island. Rodney hated the Jews he found on Eustatius. He singled them out for special treatment. Rodney wrote about the Jews of St. Eustatius, "They (the Jews of St. Eustatius) cannot too soon be taken care of - they are notorious in the cause of America and France." Rodney immediately arrested 101 adult Jewish males on the Island, brutally locking them up in a warehouse without food and water for days. He deported the heads of over thirty Jewish families to neighboring Islands. He destroyed the synagogue and burned what he could not carry from their warehouses. The homes, the property, even the clothing on the backs of the Jews were searched for treasure. He had Jewish graves dug up when the Jews tried hiding some of their personal wealth and possessions in the Jewish cemetery. Rodneys diligence robbing the Jews went way beyond just robbing the population of the Island. From the Jews alone he confiscated over 8,000 pounds sterling, an enormous sum. That amount did not include Jewish goods, ships and property. Rodney made sure to impoverish the Jews. He did not do the same to the Dutch, French or even the Americans he found on the Island. He robbed them but he permitted them to leave with their portable wealth. The French, in particular, he generously permitted to leave with their household goods boxed up. The French he knew could do the same to the British if they conquered a British Island using his precedent. But the Jews had no army. They had no navy. The Jews had piqued Rodneys greed. Privately, he happily wrote to his family with promises of a new London home. To his daughter he promised, the best harpsichord money can purchase. He confidently wrote of a marriage settlement for one of his sons and soon to be purchased commission in the foot guards for another son. He wrote of a dowry for his daughter to marry the Earl of Oxford. He noted he would have enough to even pay off the young prospective bridegrooms debts. The wealth that Rodney stripped from Statia was in excess of 15,000,000 pounds, an incredible sum. Whatever treasure he could take from Statia, whatever he could steal from the Jews, from the merchants who arrived in the harbor for the next few months, Rodney was entitled to a piece of the treasure as his personal share. Rodney was not a wealthy man. He had enormous debts from a very lavish lifestyle and heavy gambling. But when he realized the enormous treasure the Jews and the merchants of Statia had, with the possibility of even more, he violated his direct orders. Rodneys orders were to destroy the supply depot of St. Eustatius. He was to shadow and stop the French West Indies Fleet. He was to return north to aid the British forces fighting the American Revolutionary armies. Almost two months after he captured St. Eustatius, Rodney diverted a significant part of his fleet to carry the fortune, his fortune, from Statia back to England. It weakened his fleet. Difficult, irascible and arrogant, Rodney was finally prevailed upon to send a small part of his fleet North. He chose to further delay his departing until July. The delay cost the British the war.

The French West Indies battle fleet slipped away north. A second French fleet crossed the Atlantic to aid the American cause and unite with the West Indies Fleet. Rodney dawdled. He was seeking his gold in St. Eustatius. By the time he sailed it was too late. The combined, powerful French fleet had closed the Chesapeake Bay. George Washington and the American army had trapped Cornwallis at Yorktown. The British, in a vice, had no hope of reinforcements or supplies. The war was lost. Ironically, the Jews of St. Eustatius, linked to the anti-Semitic greed and hatred of a British Admiral, helped win the American Revolution. Statias commerce was severely damaged by the British. Most of the Jews moved on. Some became founding fathers of Jewish communities on other Islands, such as St. Thomas. Statias economy attempted to revive but never did.

The synagogue fell into abandoned ruin until its walls were wonderfully restored a few years ago as part of Statias cultural awareness and history. The cemetery, the homes, the ruins of the warehouses along the shore, the rebuilt synagogue with its mikveh, chametz oven are present day quiet testimonials to the long gone, once vibrant, Jewish life on St. Eustatius. They are silent testimony to how the Jews helped save the American Revolution. A journey to Statia is a journey back into the time of the Golden Rock. It is a journey, directed by the hand of Providence, to the Golden Door that millions of desperate Jews and oppressed peoples from around the world, would find open to them in the years to come. .

Postscript : Ambassador Mordecahi Arbell was the Israeli Ambassador to Panama and Haiti in the 1990s. He spent over thirty years researching and writing dozens of articles about the Jews of the Caribbean. He wrote the single most comprehensive book on Jewish Caribbean History The Jewish Nation of the Caribbean. Arbell has been a research Fellow at the Touro National Heritage Trust. He has been with the American Jewish Archives, The Ben-Zvi Institute, and at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Many records needed to understand the Jewish Caribbean require disciplines with multiple language skills. Finding records re: the Jewish Caribbean requires a dogged diligence to hunt them out. Most of the St. Eustatius records were destroyed by the British or lost when needed at the law suits against Lord Rodney. (Rodney had been elevated to the Peerage after destroying St. Eustatius. He died a far cry from being a wealthy man. Lawsuits hounded him for the balance of his life. He survived a censor in Parliament, which was led by Edmund Burke, for his actions in St. Eustatius. He survived because the vote, strictly along party lines, protected him. ) Arbell emphatically wrote in his history re: St. Eustatius, The majority of the ships that sailed to and from St. Eustatius were of Jewish ownership and navigated by Jewish captains, especially those that traded with fellow Jews in North Africa and North America. After 1760, there anchored in St. Eustatius between 1,800 and 2,700 ships annually. In 1779 the number reached 3,531. Arbells academic conclusions about the Jews of St. Eustatius and their impact are maximalist. He was certainly not claiming that all the ships and all the trade were in Jewish hands. His conclusions are tempered by the nature of Jewish life, the character of the anti-Jewish world post the Spanish expulsion of 1492 and the issues of New Christians vs. Old Christians. Jewish refugees were forced to make many adjustments to simply exist. Many Jews had to take Christian partners, as the head of their enterprises. It was a cost of doing business. It made identifying Jewish owned firms extremely difficult. Arbell understood the interlaced network of Jewish finance, commerce and communal life that stretched across long distances and across national borders. His view of Jewish St. Eustatius, even if only partially true, is significant and cant be arbitrarily or summarily discounted. The Jews of St. Eustatius have been give too little recognition for their part in creating the economic network that made Statia into the economic powerhouse it was. Too little attention and credence have been given to Jewish Statias contribution to the success of the American Revolution. Much has been written about Haym Salomon, the Financier of the American Revolution. Haym Salomon was an important factor and broker but he alone did not save the American Revolution.

Edmund Burkes Parliament speech, in Defense of the Jews of St. Eustatius This island was different from all othersa magazine for all the nations of the earth. It had no fortifications for its defence; no garrison Its inhabitants were a mixed body of all nations and climates The Dutch commander yielded up the dominion A general confiscation of all the property found upon the Islandwithout regard to friend or foe and a sentence of general beggary pronounced in one moment upon a whole people. A cruelty unheard of in Europe for many years The persecution was begun with the people whom of all others it ought to be the care and the wish of human nations to protect, the Jews the links of communication, the mercantile chain the conductors by which credit was transmitted through the worlda resolution taken (by the British conquerors) to banish this unhappy people from the island. They suffered in common with the rest of the inhabitants, the loss of their merchandise, their bills, their houses, and their provisions; and after this they were ordered to quit the island, and only one day was given them for preparation; they petitioned, they remonstrated against so hard a sentence, but in vain; it was irrevocable. They asked to what part of the world they were to be transported: The answer was, that they should not be informed they must prepare to depart the island the next day; and without their families The next day they did appear to the number of 101, the whole that were upon the island. They were confined in a weigh-house strongly guarded; and orders were given that they should be stripped, and all the linings of their clothes ripped up, that every shilling of money which they might attempt to conceal and carry off should be discovered and taken from them. This order was carried into rigid execution, and money, to the amount of 8,000 (pounds) was taken from these poor, miserable outcasts thirty of them were embarked on board the Shrewsbury, and carried to St. Kitts. The rest, after being confined for three days unheard of, and unknown, were set at liberty to return to their families, that they might be melancholy spectators of the sale of their own propertyOne of these poor wretches had sewed up 200 Johannes in his coat he wasturned from among the rest and set apart for punishmentTwo more Jews had been detected also in breach of the order for delivering up all their money. Upon one of them was found 900 Johannes. This poor mans case was peculiarly severe, his name was Pollock. He had imported tea contrary to the command of the Americans, he was stripped of all he was worth, and driven out of the island.; his brother shared his misfortune, but did not survive them; his death increased the cares of the survivor, as he got an additional family, in his brothers children, to provide for. Another Jew married his sister; and both of them following the British army, had for their loyalty some lands given them, along with some other American refugees, on Long Island, by sir William Howe: they built a kind of a fort there to defend themselves; but it was soon after attacked and carried by the Americans; and not a man who defended it escaped either death or captivity; the Jews brother-in-law fell during the attack; he survived; and had then the family of his deceased brother and brother-in-law, his mother and sister, to support; he settled in St. Eustatius, where he maintained his numerous family, and had made some money, when he and his family were once more ruined, by the commanders of a British force, to whose cause he was so attached; and in whose cause he had lost two brothers, and his property twice. Another Jew, named Vertram, was treated with as much severity, nor had the commanders any pretext for his profession, for confiscating his property; he sold no warlike or naval stores to the enemy he was left a beggar. These cruelties were soon followed by others as dreadful.

Partial Bibliography: History of the Jews of the Netherlands Antilles, American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, 1970 Isaac S. and Suzanne A. Emmanuel, Through the Sands of Time, A History of the Jewish Community of St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, by Judah M. Cohen, Brandeis University, The Jewish Nation of the Caribbean, The Spanish-Portuguese Jewish Settlements in the Caribbean and the Guianas, Mordechai Arbell, Geffen Press, Jerusalem, 2002 St. Eustatius in the American Revolution, J. Franklin Jamison, the American Historical Review, Vol. 8, No. 4, (July, 1903), pp. 683-708. The Other Road to Yorktown, John Millin Selby, 1976 Louis Arthur Norton (Noted Naval Historian) http://www.jewishmag.com/107mag/jewsofeustatius/jewsofeustatius.htm Academia EDU: Edmund Burke, the Atlantic American war and the' poor Jews at St. Eustatius by Guido Abbattista

Statia Toruism: http://www.statiatourism.com/pdf/HistoryJews.pdf http://www.steustatiushistory.org/HonenDalimSynagogue.htm

Jerry Klinger is President of

from the October 2014 Edition of the Jewish Magazine Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used. |

|

| All opinions expressed in all Jewish Magazine articles are those of the authors. The author accepts responsible for all copyright infrigments. |