|

Lt. Col. John Henry Patterson

The Christian godfather of the Israeli Army

The godfather of Yonni Netanyahu

By Jerry Klinger

Medallion of the Zion Mule Corp

There is no exaggeration; Patterson was the commander of the first Jewish fighting force in nearly two millennia. And as such, he can be called the godfather of the Israeli army.

- Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu

Never in Jewish history has there been in our midst a Christian friend of his penetration and devotion.

- Vladimir Jabotinsky

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stood on the auditorium stage of the Beit HaGedudim Museum, the Jewish Legion Museum, in Avihayil. Three hundred guests filled the room. Israelis dressed in Israel casual, open shirts, even jeans. Foreign guests in suits and ties. Only one officer present was in full dress uniform, Col. Jefferson, the British Military attach from the British Embassy accompanying the British Ambassador. A projected image of Lt. Col. Patterson filled a huge screen behind the Prime Minister. The text adjacent to the picture boldly read, We salute you, Lieutenant Colonel. Patterson.

The Prime Minister spoke to all and directly to Alan Patterson, the Colonels grandson and last family. Alan sat in the front row. Prime Minister Netanyahu spoke historically. He spoke with feeling, context and emotion that came from the heart. There is no exaggeration, Patterson was the commander of the first Jewish fighting force in nearly two millennia. And as such, he can be called the godfather of the Israeli army.

It was a curious statement to those who knew nothing about Colonel Patterson. Patterson was a Christian. A Christian was the Godfather of the modern Israel Defense Forces, not a Jew.

I sat in the front row next to Alan. As the Prime Minister named a list of Israelis who helped make the return of the Colonel possible, I heard him say in Hebrew, especially Jerry Klinger. It was a surprise. I had long grown accustomed to the Israeli penchant for acknowledging few outside of themselves for accomplishments that benefited Israel. It remains an unpleasant experience of many friends of Israel to be supplanted by Israelis rushing to take credit for things they did not do. Part of the Israeli mythos, rooted in the foundation story of the country, is we did it all by ourselves.

Israel did much by itself; there is no denial of that. But without help from Christians working together with the Jews, Israel may not have come about. The return, the long overdue act of respect, honor and duty to Colonel Patterson absolutely would not have happened if it had not been for the common efforts of Israelis, Americans, Canadians, Jews and Christians who came together in common purpose.

The Colonels story, the Zion Mule Corps, the Jewish Legion, his personal high sacrifice for Zionism, for the Jewish people, why the Colonel was important, why what we were doing was importantthe Prime Minister got it right. The media pretty much got it wrong.

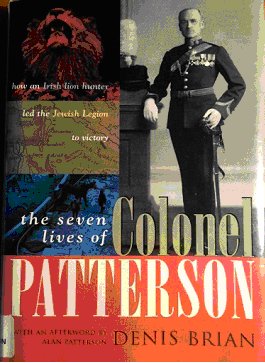

Four Years ago, I read a biography of Colonel Patterson by Denis Brian, The Seven Lives of Colonel Patterson. The Colonel lived a fascinating, almost swashbuckling life, more exciting and exotic than an Errol Flynn Hollywood movie. At the end of the biography was an afterword by Alan Patterson. Alan wrote about an obligation he had to complete his grandfathers final wishes.

The last is to organize removal of JHPs (John Henry Patterson) and Francies (his grandmother) remains and relocate them suitably in Israel. One of his last wishes was to be buried with his troops. Near the Beit HaGedudim Museum, dedicated to the Jewish Legion, there is a cemetery where many of the legionnaires are buried, and this presumably would be the most appropriate place, provided that Francie could be interred there as well. This will, I fear, entail significant dealings with bureaucrats. The Col. Was used to bulldozing through, skirting or, when essential, ignoring bureaucracy and its requirements, skill that could prove very useful to me now.

Alan was not confident that he had the ability of fulfilling the Colonels wishes. He was concerned about the fight and the focus of time needed to wade through the jungle of bureaucratic obstacles to do the job.

I read what Alan wrote. Having successfully finished the seven year struggle to rebury the abandoned and forgotten last descendent of Theodor Herzl, his grandson Stephen Norman, with his family on Mount Herzl, I understood the extreme difficulties that Alan would have to face. Ironically, Norman was the only Zionist in Herzls family. He was the only Herzl to have been to Palestine and wanted to be there. He was denied the ability to return to Palestine by the British Mandate government because he was a Herzl. Reburying him should have been a simple Zionist duty. It became a Zionist ordeal.

Fulfilling the Colonels last wishes was a debt Israel and the Jewish people owed him. I owed him. Doing the right thing did not mean it would be easy. As Alan had feared, bringing the Colonel home did turn out to be long and difficult.

A Christian friend, a Canadian admirer of Colonel Patterson, Todd Young, put me in contact with Alan. I called Alan and met him in Boston.

At Avihayil, Alan spoke before the Prime Minister did. Alan picked up the story.

In an afterword to a bibliography of JHP, I wrote that one of the tasks ahead of me at that time was the re-internment of my grandparents. Jerry contacted me as soon as he read that and offered his services. At first I was reluctant to accept, feeling that this was something that I needed to do personally. Pondering all the bureaucratic work involved in both Israel and the US, with consideration I decided that Jerry's offer was too good to turn down. And here we are.

John Henry Patterson was born November 19, 1867 in Forgney, Ireland, a small town known because it was the birthplace of poet Oliver Goldsmith. Pattersons father was a Protestant, his mother a Roman Catholic. Patterson was raised as a Protestant. He did not have any deep religious convictions. Like most young people, he read the Bible more as literature and history than theology. Not much is known about his childhood. According to Alan Patterson, JHP most likely lied about his age when he joined the British army. He may have been 17.

Coming from a family of modest means, the army was an honorable way up in the world. He quickly showed a natural ability in Military Science and was sent to officers training school. He studied and successfully graduated as an officer in the British Army. His education had an emphasis in engineering.

Patterson was sent to India. His training as an engineer would shape the course of his life.

Early in 1898, Patterson was engaged by the Uganda Railway commission to build a bridge over the Tsavo River in present day Kenya. British Imperialist goals required the construction of railways to control East Africa. They were in direct competition with German Imperialist plans. Spanning the Tsavo River was vital to the railroads progression. Patterson arrived in March of the same year. The construction of a bridge, especially difficult in primitive areas, was not an impossible project. It proved nearly the opposite.

Patterson arrived and set to work, methodically, with his objective firmly in mind. Time was of the essence. The work progressed swiftly and almost as swiftly ground to a halt. Suddenly, lion attacks began killing the workers. Lions were part of the local wildlife. Lion attacks on humans were known but uncommon. The lion attacks continued. Brazenly, the lions dragged men out of their tents at night while they slept to kill and feed on the bodies.

Traditional responses were implemented, thorny bush barriers, called bomas, were erected around the camp. Huge fires burned all night. Rigid curfews instituted. Sentries were posted. The lions cunningly were not deterred. The killings of the workers accelerated. Over a hundred men had been killed. The lions seemed to enjoy killing for the sake of killing. Fear gripped the work camp. Nothing stopped the killings.

The terrified workers refused to continue. The lion attacks were not normal. It was as if some terrible evil spirit had come into the camp with Patterson. The men began deserting the work site. Work came to halt. Pattersons authority was challenged. His career as a military engineer could be finished. The railroad faced serious financial damage. British Imperialist efforts would be dangerously delayed. Patterson, personally, was threatened by the superstitious men.

Patterson was an experienced tiger hunter from his service in India. Patterson knew he was dealing with a pair of very large animals. Night after night he would go out in search of the killer lions, only to fail again and again in locating them. Early December, he killed the first lion. A few weeks later, Patterson was nearly killed by the second lion after the wounded animal charged him. Cold courage and a steady aim brought the second beast down.

The lions were dead. They were incredibly huge beasts measuring over nine feet in length from their noses to the tips of their tails. The lion corpses were brought into camp for the men to see. It took eight men to carry each one.

Congratulations poured into the Tsavo camp from around world. The terror of the man eating lions of Tsavo was world news. Patterson, the great hunter, the man of courage, steadfastness and determination, was acclaimed everywhere, even in Parliament.

Construction of the bridge over the Tsavo River was completed in February of 1899. Patterson sold the lions skins to the Fields Museum in Chicago. The museum had them stuffed and mounted. The man eaters have been on display since 1924.

Pattersons fame and courage in the face of darkness rose to pop culture heights after he wrote a book based upon his experiences published in 1907, The Man Eaters of Tsavo. The book went into multiple printings. Three movies have been made about Patterson and the Lions of Tsavo. The most recent was 1996, The Ghost and the Darkness staring Val Kilmer.

With the completion of the bridge over the Tsavo River, Patterson was transferred to the Essex Imperial Yeomanry. He served with distinction in the Boer War, 1899-1902, earning the Distinguished Service Order and eventually his final rank, Lt. Colonel. During the Boer War, Patterson made numerous key command contacts. He would call upon the contacts later in his efforts with and on behalf of the Zionists, with extraordinary results.

Lord Elgin appointed Patterson the Game Warden (Superintendent) of the game reserves in East Africa after the Boer War. While leading a safari, 1908, for Audley Blyth, son of James Blyth, 1st Baron Blyth, and his wife Ethel, Blyth was mysteriously shot. Rumor accused Patterson of shooting Blyth over an affair with Mrs. Blyth. Witnesses testified that Patterson had not been in the Blyth tent when he was shot. Pattersons actions were investigated and he was not so much as censured. Yet, the wagging tongues continued. His reputation was forever sullied among proper British society. His career in the military did not progress. He retired from the army in 1911. Three years later World War I broke out.

Patterson volunteered and was sent to Flanders. The Blyth affair and his broken reputation followed him. He was refused a permanent command in Europe. On his own initiative and expense, 1915, Patterson traveled to Egypt where his old friend General Maxwell was in charge.

To Continue, Click Here

~~~~~~~

from the Winter 2015 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used.

|