| |

2015 |

|

| Browse our

|

The Star of David is a sign of resistance in the Vilna Ghetto during WWII

The Daymare By Elaine Leeder © 2015 It begins as I turn out the lights and prepare to settle down for the night. The room is dark, the bed is comfortable and cozy, and I eagerly await my restful sleep. But I am still awake when a cold feeling comes over my body. I begin to be anxious, for I know what is coming. All of a sudden, the fear takes overvisceral and terrifying. I am falling into a pit; it is large, emptying into an abyss that spirals downward. The spiral reaches to infinity, and my fall down this hole goes on forever, without end. I stay conscious. I begin to think that this life I know will cease, and that everything I know to be reality is, in fact, temporary. The life I live is an illusion, to be shattered and end with no control on my part. I will die; it is inevitable. And the world will go on without me, my existence wiped out in an instant. Completely conscious, I am falling forever into this pit. It is my death, and it will never end. The pit is dark. The farther I fall, the smaller it gets. There is no one to help or save me. I must deal with it myself, as I have done since the horror beganas I have done since I was eleven years old. My father said I would outgrow it. My husband held me when I was a young woman, telling me he was there with me. Now I have these daymares alone. They have come for fifty-nine years. Will they ever end?

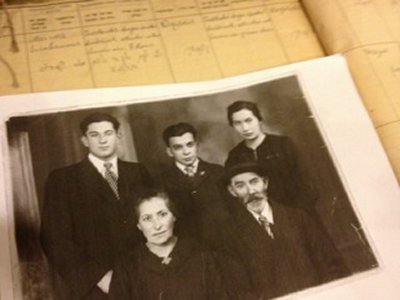

My father and his family before he left Lithuania in 1939

HOW IT BEGAN

We are sitting in a car in the dark. We are waiting, my brother and I, for our parents to emerge from the apartment in Brooklyn, N.Y., where they went upstairs hours ago. We do not know why we are sitting down here, but we continue to wait. When he went up, my father was hopeful and eager to meet with whomever he had come to see. He seemed wary but anxious. Many hours later, my father emerges, almost carried by my mother, helped into the car as if he is an invalid. He is weeping, quaking actually. He looks like a broken man, so much did he age in those few hours in that apartment. We dont know what happened, but we know something horrible occurred. Silently we drive back to Boston, many hours away. We sit in silence, knowing that we should not say anything. Nothing more is ever said of that evening. My family guards the secret well. Over the many years since then, I have tried to understand what happened that night, but the pieces never fully come together. My father, Zalman (Samuel) Sneierson, came to the United States in January of 1939. Family members in this country had sent money for his eldest sister, Althea, to immigrate, but she said she wanted to stay behind to care for their ailing father (Eliezer, after whom I was named) and told her brother to go instead; she asked that she be sent for later. And so the eldest son was the first to go, in keeping with heritage and traditionand the sacrifice of Althea. According to family folklore, my father was one of only seven Lithuanians allowed into the U.S. that year because of immigration quotas. Actually, he had been number eight on the list, but murky dealings behind the scenes moved him up in the queue. A Lithuanian passport kept by the family has a Nazi stamp, indicating that he crossed through Germany during the military buildup for World War II. He described being accompanied through Germany by an S.S. guard, moving through Berlin, and seeing the mobilization taking place. He ended up in Le Havre, France, and sailed from there to the U.S. Family members took him in, and he was inducted into the U.S. Army, serving in South Carolina. He also met the woman who would become my mother, a first-generation Jewish woman whose family came from the Ukraine. Throughout those years, he kept up a correspondence with his family back in Lithuania. The relatives he had left told him in letters and postcards how glad they were that Zalman was not in Lithuania when the Soviet Army had come looking to conscript him. Things were becoming more difficult financially, they said, asking that he send money to help them survive. In 1940, Eliezer died of natural causes, and was buried in the Jewish cemetery not far from the family home at 52 Gedamis St. in the town of Kupiskis (or Kupishok in Yiddish). After the war, Samuels life took on a normalcy in the States. He worked with an uncle and became a junk dealer, first using a cart, then a truck, and then opening their own business, what would now be called a recycling plant. His work was salvaging the discards of peoples lives, as I have tried to salvage his story and his family's. He told his children that on the ship coming over, he had thrown away his teffilin (the phylacteries worn every day by Jewish men as they say their morning prayers). But soon after arriving, he bought another set and continued to lay teffilin every morning for the rest of his life. He became a key member of his Orthodox synagogue, attending services often. Over the years, he introduced his children to many of the trappings of the Old World. Its smells and traditions permeated the house. The food made by our mother, an excellent cook, was often Eastern European: borscht, rye bread, herring. My father would sit in his chair all evening studying religious tracts, and years later as he lay dying, his physician paid for a private room overlooking the river so he could continue to pray. The doctor said it was his honor to provide this for such a righteous man, as a way of showing respect for my fathers Old World dedication to his faith. After the war broke out in Lithuania in 1941, Samuel never heard from any family members again. As a child I would watch him reading Jewish newspapers, looking for mention of his family, fearing the worst, hoping they had survived. He never saw their names. I was born in 1944, and my brother in 1949. It was in the mid-1950s when we took that painful trip to Brooklyn which we both remember, when my father learned the fate of his mother, his sister, and his brother. Someone he saw upstairs in that apartment who had escaped from near Kupiskis told him the horrible details of their deaths. Samuel never spoke about what occurred. Night after night he sat quietly, davening in silence. Usually morose and quiet, he turned to his prayer books and his religion to help him survive. Though I must have picked up that something horrific had happened, I never knew any details nor the family's actual story. I knew but did not know what had occurred. The family secret was both constantly present and yet never spoken. It filled the air, sitting over us all like a cloud of sadness. My father lived a life of vivid contrast, by day salvaging old metals and clothinglater selling used tiresand by night a biblical scholar and religious man. He interacted with all types, even going to a bar now and then with friends quite unlike himself in religion or values. Still, he would come home at night, take out the scholarly tomes, and sit quietly with them, finding solace in the ancient texts.

Samuel died in 1983. I became a professor of sociology, studying the dynamics of wife battering and sexual assault, working with victims of domestic violence and other forms of trauma. In the mid-1990s, I was a visiting scholar at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., learning how to teach the Holocaust, which had become one of my passions. I had clearly been drawn to the dark side of society, and knew that it came from my background in a family with genocide as part of its history. I had fought for social justice my whole life, marching with Martin Luther King in 1962, working as an antiwar activist and as a militant feminist. I was now married and had a wonderful daughter, who was growing into a woman also dedicated to social justice. In the mornings at the museum, I was taught the details of the Holocaust and worked with noted scholars. It was an intellectually stimulating atmosphere, filled with knowledge, demanding teachers, and brilliant scholars as my fellow students. In the afternoons, we students worked on our family stories. On one powerful day, using the JewishGen website, a remarkable tool for information about the families, shtetls, and other details of the lost peoples of Europe, I came upon a handwritten list of all the victims of the killing of the Jews of Kupiskis, Lithuania. It had been compiled by a public health nurse from the nearby larger city of Paneveys, where my father had attended yeshiva. The list sent chills down my spine. Among the more than 800 people listed clearly was my grandmother, Yenta Leah, age 64, my aunt, Althea (Alte), age 28, and her uncle Herse (Hershel). It said that he was 20, but in fact he was 17, having been born in January of 1924. I printed out the list and ran to the phone to tell my brother what I had found. That was the beginning of the search for the details of our family's history. It was a turning point in my quest for information about my family's demise. A few years later, my brother called to say there was a story in the news about a Nazi collaborator in Kupiskis, Lithuania, who was about to be deported from the United States for falsifying documents when he immigrated here. On January 14, 2002, the Justice Department initiated proceedings to revoke the mans U.S. citizenship because of his participation in the persecution and murder of Jews and other civilians during the Nazi occupation of Lithuania in 1941. The complaint filed in U.S. District Court alleged that Peter John Bernes (a/k/a Petras Bernotavicius), 79, worked during the summer of 1941 as deputy to Werner Loew, the Nazi-appointed mayor and police commander assigned to Kupikis, Lithuania. It stated that Bernes, who after his immigration had settled in Lockport, Illinois, participated directly in the process of removing condemned prisoners from jail so they could be taken to nearby killing sites. According to the complaint, more than 1,000 Jewish men, women, and childrenapproximately one-fourth of the town's populationwere murdered in Kupikis by armed men under Loew's command. More than 300 other local residents, among them a nine-year-old boy, were arrested and murdered as political prisoners. Bernes worked in an office near the overcrowded jail where victims were held without adequate food and were beaten before being shot to death. Michael Chertoff, assistant attorney general in charge of the departments Criminal Division, said: "The case against Bernes demonstrates the Justice Department's commitment to ensure that individuals who participated in genocide and other crimes against humanity find no refuge in the United States, regardless of when those atrocities occurred." I immediately called Michael Chertoff who was a warm and helpful man. He asked if I wanted to know the details of the killing of the Jews of Kupiskis, which I certainly did. The entire population of Jews, he told me, were marched to a pit outside of town and summarily shot by Bernes and a few Nazis and Lithuanian collaborators. Bernes had just graduated from high school when he was appointed as an assistant to the Nazi commandant, responsible for ensuring the smooth movement of Jews and Communists to their killing places outside town. This was the first time I had heard the gory details of my family's killing. It had been alluded to in the past, but now the story was corroborated. Finally there were facts rather than the vague miasma that had hung over my head for so long. Life went on; I continued to teach about the Holocaust, often using as an introduction to classes or lectures a family photo of Samuel, Eliezer, Yenta Leah, Althea, and Hershel taken just before Samuel emigrated as a handsome 19-year-old. I had long considered myself the memorial candle to my fathers family. Much has been written over the years about the children of Holocaust survivors having the intergenerational transmission of trauma. Although my father was a refugee and not a survivor, the family and its demise had long been a fact of our lives. I had lived with it since I was a child, and always knew I must do something to right the injustice that was done to my family. Invariably in a Holocaust family, one child is unconsciously chosen to be a memorial candle, to carry the story, to remember and to dedicate his or her life to the memory of the Shoah (burning by fire, a Hebrew term for the Holocaust). Author Suzanna Eibuszyc has said, That child takes part in the parents emotional world, assumes the burden, and becomes the link between the past and the future. (On Transmitting Family Trauma to the Next Generation, The Jewish Magazine, 2011.) It was not until my fifties that I found out there was a name for what I had been doing and feeling all my life. I was comfortable with that role and took it on gratefully, albeit not consciously. It was not until later in my life that I could actually see and name my role in the family. It gave my life purpose, making me feel that I was contributing in some way to the repairing of the tear in the universe, as articulated in a Jewish tradition called Tikkun Olam. The house we had grown up in was dark and depressed. Curtains were drawn at all times, to keep out the gentiles who might do us harm. Since it was an Orthodox home, much time and attention was paid to the rituals and traditions of Judaism. Because there was a boy in the family, much love was devoted to him, since he would say the Kaddish when the parents died. I was a troublemaker in the family, calling attention to inequities and favoritism that were blatant to me. I was told I was crazy and would end up a schizophrenic, like an uncle on my mothers side of the family. As a child I well remember sitting behind the curtain on the second floor of the synagogue where all the women sat. My father is sitting below, with my brother and my best friend, Michael, who is there with his father and brother. Oh, how I long to be down there with the menwhere the action is, where they cry and bobble in deep, intense prayer. But I am upstairs with the women, told to be quiet, to cover my head and be a good girl. I resent it and want to be with them, let into the inner world that they inhabit, closed to me forever because I am a girl. My father has been doing this for his whole life, seeming to know something that I would never know. I am not valued; I am not a precious metal like the ones he salvaged as a junk dealer. Instead I am a second-class citizen, and I feel it deeply. Because of this sense of inferiority, I slowly but surely pulled away from the family, finding success outside the home. Being the memorial candle helped me to have a purpose in life, and to call attention to injustices in the world. The gender disparities were striking if one felt them daily, so that became my first issue of concern. In one incident in my home, the entire family was seated at tables for a Passover dinner. One table where many women were sitting began to fall to the floor. One cousin said, Let it fall; it is only the womens table. I was outraged and said so. I was marginalized for saying such a thing in public, ending up leaving the table in tears, since no one else acknowledged the insult. At other times I lashed out in anger at the discrimination I felt. Eventually I moved away from my family rather than endure such slights on a daily basis. When my mother died, I had been promised her diamond ring. It was precious to her, a valuable stone she was given by her own mother. At the reading of the will, my brother and father sought to take the ring from me, saying it was intended for my brothers future wife. (He had no one in his life at that time.) I screamed in anger again, saying I hated them for all the years of discrimination. Once again I was not valued; I was second class in this family. It hurt my father so much when I lashed out that when he died just eighteen months later, his will said, She shall receive five thousand dollars or twenty percent of the estate, whichever is less. And I received just $5,000. The pain lasted a long time. There are many theories about how one is designated a memorial candle. It is often the eldest child in the family who is chosen, either consciously or unconsciously. My father had long said that I looked like his sister Althea. Being a memorial candle is part of the intergenerational transmission of trauma. One can never be sure how one is designated, but I certainly knew at a young age that I was supposed to honor them and DO something. I had many of the characteristics that have been described in memorial candle children. I had the impaired self-esteem with persistent identity problems; I felt an over-identification with my fathers victim/survivor status; I had a great need to be a super-achiever to compensate for my fathers losses; and I carried the burden of being replacement for his lost relatives (Natan Kellerman, Transmission of Holocaust Trauma, www.yadvashem.or/yv/en/education/languages/dutch/kellerman.pdf). These memorial candles also have a fear of catastrophic events occurring, as well as nightmares of persecution, unresolved feelings regarding anger, and guilt at feeling anger. Other descriptors of these memorial candles include either exaggerated closeness to family, or exaggerated disconnection from family. It was the exaggerated disconnection that I felt. I distanced myself early on, making friends and being successful in arenas outside of the home. I felt different and made sure to stay that way, not wanting to be part of a family that I felt so scapegoated by. I felt anger all the time; it was not a healthy place to be on a regular basis. These children also manifest difficulties in entering into interpersonal relationships. I fit all the psychological constructions, but I was unaware of them when I was growing up. The awareness only came later as I began to study children of survivors or refugees. I might not have known all the details of what occurred to my family, but I knew that I certainly carried many scars. The unconscious awareness of the trauma did not manifest itself until later in life, but I had a compulsion to do good in the world no matter what. I learned through study of children of Holocaust survivors and refugees that it was through the interpersonal relationship with my father that I learned to unconsciously displace my emotions. It might not have been talked about, but the Holocaust permeated our lives. There was darkness in the home; there was great concern that no one outside the house should know what was going on within. The family taught me to trust no one but myself and other Jews. I learned vicariously to take on the sad, depressed state of my parents. In fact, I also learned early on to escape the home, the dark moods and the angst that filled it. I was out of the house by seventeen, never returning to live there again. But I nevertheless have carried my home with me for the rest of my life. The family saw me as rejecting them; in fact, I felt that I was running for my life. My memorial candle work often meant that I would work with perpetrators of various forms of violence. I was fascinated by evil and what brought people to commit atrocities. For the last 17 years, I have worked in prisons with men who have committed murder, to help them change but also to understand them. Perhaps it was also to understand those who committed atrocities against my own family. I also needed to make a tangible statement about genocide, feeling that teaching about it was not enough. Even though I taught thousands of college students about such matters, I decided in 2007 to work on the construction of a Holocaust and Genocide Memorial Grove on the campus of Sonoma State University in California, where I taught. I found a donor (a friend, David Salm, whose parents were Holocaust refugees from Germany), and together we found a sculptor to build a long-lasting memorial on campus. Jann Nunn created a touching and dramatic design of train tracks moving to a final point where a tower of eternal light beams. The railroad ties for the tracks are bricks that were sold to honor victims of the Native American genocide, the Armenian genocide, the Cambodian (Pol Pot) genocide, the Holocaust, Darfur, and the Pacific victims of the Japanese. A very moving opening ceremony for the Grove was held in 2009, and then again in 2013 when a sapling from the original Anne Frank tree in Amsterdam was planted there. Obtaining the sapling was a competitive process, but the Anne Frank Foundation in New York deemed the university an appropriate location, one of eleven in the country. Others included the White House, the Bill Clinton Foundation in Arkansas, and the Childrens Museum of Indianapolis. The tree has been maintained by a dedicated team of arborists and is thriving on the Sonoma State campus as part of the Erna and Arthur Salm Holocaust and Genocide Memorial Grove. In fact, there is a brick on the site honoring my aunt, uncle, and grandmother from Kupiskis, as well as the numerous cousins lost on my mothers side in Poland during the Holocaust. The Grove became a symbol of my commitment to combatting injustice, and was a beautiful and fitting memorial to all who suffered. I was now a woman working on making a life and honoring my family members killed in Lithuania. It gave my life meaning and purpose, and helped heal the painful wounds of childhood. Yet it would be many years before I went to Lithuania to finally put all the pieces together.

THE TRIP TO LITHUANIA

As we approached the field, we could see a series of pits surrounded by stone walls. These were the pits where thousands of Jews were marched to their deaths. We had seen photographs of this horrible place, with lines of people waiting patiently to go to where their lives would end. Now we were actually here. The souls of those killed were under our feet. Carefully and silently, we all walked, in awe of the tragedy that took place here. What were those killed thinking as they faced the end? Were they praying, resisting, going with friends and family? Were they alone? Were they frightened, at peace? What was their experience as they faced the reality that it was all about to end? We were in Paneriai, the largest killing place in Lithuania. For years I had wanted to visit Lithuania, the place from which my father had come. When I would ask if he wanted to go with me, his answer, in his heavy Eastern European accent, was always the same: Why would I want to go there? They killed my people, and I was glad to get out of there. I never pursued it, but as the years went on, I continued to feel compelled to visit. It was my heritage. At first I looked like his sister, my lovely aunt Althea. Later I began to look like my grandmother, Yenta Leah. I knew that eventually I would go, but as the years passed, it became even more imperative. Time was marching on; I was not getting younger. My brother and I agreed it was time for the journey we had put off for years. I was approaching 70; he was 65. We finally booked our trip for the summer of 2014. As the time approached, it loomed over our heads with a distinct fear, as well as the interest we had always felt. After all, we had lived with the story for our entire lives. We would hear other people talk about the Holocaust as a historical fact; for us, it was part of our own lives, a part of our identities we had to explore. The trip for me was a pilgrimage. The missing facts in my knowledge needed to be fleshed out. Travel in general is hard work, but being a pilgrim is even harder since one is truly stretching beyond the usual boundaries of a persons life, making a very personal experience that involves every aspect of ones being. It was unlike any travel I had undertaken before: I felt like I was heading for sacred ground. Richard Niebuhr once said: Pilgrims are persons in motionpassing though territories not their ownseeking something we might call completion, or perhaps the word clarity will do as well, a goal to which only the spirits compass points the way (as quoted in Philip Cousineau, The Art of Pilgrimage, Berkeley: Conari Press, 1998). I needed clarity about the place my family came from, clarity as to what went on there and what this place is today. I needed to know what I did not know. Thus I suspended judgment and expectations. Everything that would occur was what was supposed to occur. I would find out; it would emerge. All I had to do was put myself in the place of going. The rest would unfold. My destination, I knew, would be as different as day and night from the Orthodox home Id grown up in in an industrial city north of Boston. My mother had been born there, and my father had relatives there, a solitary man finding his way in typical immigrant fashion to where there were people from his own or a neighboring area. In Lithuania, he had been a biblical scholar and a soccer player. His family had owned a small parcel of land on the outskirts of Kupishok, a typical shtetl of almost 800 Jews and 2,000 Lithuanians. They had lived harmoniously for generations. My grandmother and my auntwho also was a town hall clerk, literate and respectedtended a small shop in the town. My grandfather traveled all over Europe as a merchant, and had even gone as far as South Africa. My father stayed home to help the family, to mentor his younger brother Hershel, and to study. He was a dutiful son, well loved by his family, but also was involved in Betar, an underground Zionist movement. The family was prosperous, having lived in the area for hundreds of years. My trip, called the Jewish Heritage Tour of Lithuania, was arranged by Howard Margol and Peggy Freedman. Its organization was excellent, with all costs covered once we got to Vilnius, the nations capital. The tours purpose, their materials said, was to offer Jews an opportunity to go back to their roots, to encourage them to research their ancestors, and to enable them to see the latest efforts being made to keep Judaism alive in Lithuania. Since profit is not the main motive, all arrangements are made in a first-class manner intended to make the trip enjoyable and meaningful for all. And that they did! The tour was remarkable in its thoughtfulness and sensitivity to the travelers experience. Some of the 25 participants had families that had emigrated from the 1880s to the 1920s. Others, like myself and my brother, had lost family in the Holocaust and were there to learn more details of their lives. The program was geared to meet all these diverse needs. After meeting at a luxury hotel in Vilnius, we quickly began what seemed like a never-ending, exhausting eight-day tour of the country. The first stop was the Jewish Holocaust Museum for a morning of orientation to the tragic events from 1941 to 1943. The museum is located in a small, green building in downtown Vilnius, funded in part by the Lithuanian government in an effort to educate the public to the Shoah in Lithuania. Until the end of the Soviet occupation in 1991, these types of places did not exist. Instead, memorials to the killings by the Nazis honored Soviet citizens who had been exterminated, never mentioning that it was Jewish Soviet citizens who were wiped out. The museum outlined the numerous killing places where the atrocities took place. It also housed a letter from an S.S. standartenfhrer named Karl Jager, who wrote to his superiors in German with great pride about how he had wiped out huge numbers of Jews in the short period from June to December of 1941. The letters details were chilling, attesting to the ruthlessness of the einsatzgruppen, the roving killing teams who followed the German soldiers moving east toward Moscow as they cut wide swaths of destruction throughout the region. Most of the countrys Jews were killed in that first phase of the Holocaust in Lithuania. By the end of 1941, 175,000 of the almost 200,000 Jews in the country had been killed, most at the killing pits near their homes. The 25,000 who survived were moved to the ghettos in Vilnius and Kaunas to contribute to the German war efforts as forced labor. In the third and last phase, from April 1943 to mid-July 1944, the ghettos were liquidated, and the last of the Jews were killed. The very few of Lithuanias Jews who were still alive had been sent to the infamous concentration camps. The story of the nations Jews has not been told, and was hardly understood by the outside world since it differed from those elsewhere in Europe, where Jews mainly were killed in the concentration camps. Not so in Lithuania. In fact, scholars have argued that the genocide there was the first large-scale implementation of Hitlers Final Solution. Besides learning all this, we also had the frightening experience of being in an attic crawl space to feel what it was like for those who had to hide there. Although we were in the space for only a short time, I was appalled by it. Cramped in with five other people, I felt claustrophobic and confined; I could hardly breathe. I began to sweat even though it was cool outside. I felt viscerally frightened, my skin crawled, and I wanted to cry. I stopped breathing and felt as if I was going to die in those few short moments. I could hardly wait to get out, taking quite a while to recover my equanimity. I couldnt imagine what it must have been like to hide for months in a place like that to avoid the Nazis roundups. And yet these hiding places existed all over Lithuania, where people tried to save themselves from the inevitable. Needless to say, this was a remarkable beginning to our trip. We were immersed immediately in what we had come for. It might have been painfully hard to see, but it was a necessary way for us to learn the details of what we had known about broadly in the past. I was moved and appalled by all I learned. But it also helped put my own family's situation in the context of the larger historical events. Many more details would come later. We also learned about Lithuanian collaborators participation in the killings because of their virulent anti-Semitism. The views of many Lithuanians about the Jews were the same as those people have held from ancient times, and some also wanted to eliminate anyone who was not native Lithuanian, to make the country more pure. Many believed that the Jews were Communists who had collaborated with the Soviet Union in its takeover of Lithuania the year before. Certainly not all Lithuanians participated in the atrocities, with 723 of them being honored as righteous among the nations (an honorific term used in Israel to appreciate those who assisted Jews during the Holocaust). That powerful visit was followed by a stop at the Tolerance Center, where we saw exhibits of the life Lithuanian Jews led before the war, as well as the work being done now to educate Lithuanians about the Shoah. In fact, the director even works on reaching out to skinheads and neo-Nazis in dialogues about tolerance and social justice. Certainly, he has his work cut out for him! Lithuanias virulent anti-Semitism remains, with periodic neo-Nazi marches in Vilnius and Kaunas, and a high-ranking government official has been reported to be a very famous anti-Semitic, neo-Nazi blogger. Finally on that first day, we visited the Paneriai Memorial Museum, built on a site where 30,000-100,000 Jews were killed. The number is unknown because, contrary to what many believe, no records were kept of the Jews the Nazis slaughtered, especially in the Baltics early in their invasions. The museum location was painful in its beauty, set in a lush forest. As our group entered the park, we passed near the track for the trains that brought many Jews to Paneriai to be killed. We could hear the whistles of the trains which now move goods from the city to the countryside. It was a chilling sound. We were entering sacred grounds. The men put on yarmulkas, and the women covered their heads, as if going to a synagogue or a funeral. The pits were still there, as well as the fields where the Jews stood in line waiting to be executed through most of the years of the Nazi occupation. The feeling there is of great sadness and awe. Thousands of people buried in the cemetery were summarily executed merely for being a member of a small ethnic group. The gunshots that killed them rang out through the area as thousands marched through Paneriai on their way to their death. A guide told the story of a group of Jews who were tasked with moving other Jews to the killing pits. Eventually a few of them were able to dig a small tunnel from which they could escape and run to the forest. It was one of the few times Jews could save themselves from this horrific placea testament to human fortitude and resilience. It was the only bright spot in the whole time our group was at Paneriai. We visited a few of the pits, as well as a small museum describing what happened there. At a memorial to the dead that was quite Soviet Brutalist in architectural design, with no beauty or poetry about it, the group said Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, and left stones at the site. (This is a Jewish practice instead of leaving flowers, some say because stones are eternal, though there are many interpretations of why this is done.) The group was silent as we moved slowly from pit to memorial to museum. We were in awe of the trauma that had happened here; words were not appropriate in such a setting. This visit made obvious to me why I had come. No longer was the Shoah an artifact of history. No longer was the death of my family just a story. Here is where it began. It was a place that moved me deeply. We walked gingerly, speaking softly, often in tears. It was a place to worship, weep, and mourn for all those who had perished. None of us had ever been anywhere like it, although later on our trip, being in a place like this became a common Lithuanian experience. The only experience that may have come close to this for me was visiting the slave dungeons in Ghana, where thousands had spent their last days on the African continent before being sent off to slavery. In both places, one could smell and feel death and horror all around. In such places, one can only wonder about human beings inhumanity to each other. It is almost incomprehensible that people can do these kinds of atrocities to each other, with little remorse or sense of guilt. This is why I have worked my whole life to teach about these behaviors and to try to understand them. It is why I have worked with batterers, prisoners who committed murder, and others who have engaged in atrocities. I continue to try to learn about them, to explain them and try to stop this kind of barbarism. I have also spent time in prisons that have the same feel of death most of the timethe bars, the chains, the smells, and the inhumanity there are all reminiscent of places like Paneriai and the slave dungeons. It might be why I have been drawn to them. That evening I left the group, deciding not to attend a reception with the Vilnius Jewish community. The day had done me in. It was a deeply disturbing experience, and I needed to process it alone for many hours. Of course, I could make no sense of it. I just needed to recoup my spirit and energy to be able to go on the next day. After all, this was just the first day in Lithuania! The next day began at the Lithuanian National Archives where we were treated to a visit with the director as well as the chance to hold some rare manuscripts in our hands. However, the most powerful experience for me was going into the stacks and finding the records from my fathers village. The book was in plain sight, on a shelf with information about other shtetls as well. I reached for the one from Kupiskis and asked my brother what some of the birth dates were for family members. My uncle Hershel had been born in 1924, and I was holding the record from that year. I opened it, and the first record was that of his birth, including who did the ritual circumcision, the names of my grandparents, and the date. My brother said he had seen this on the JewishGen website, but I had not, and it was a thrilling and moving experience to find records of my family right there in plain sight. We were also able to visit the small Jewish community that now exists in Vilnius. The best part was attending a Sabbath service run by students of the Jewish school there. Preschoolers were singing many Jewish songs that we all knew as a group. We sang along as they said the Kiddush over the wine, the prayer over the challah, and the lighting of the Sabbath candles. All the members of the group were in tears, because here was a new generation of Jews, children who were carrying on the traditions that the Nazis had tried to wipe out. We continued to weep as the group participated in traditional rituals, but in a place that held even more meaning because of what had happened here. It was as if our ancestors were being reincarnated in these children, who would remain here and keep the traditions alive. It was a powerful moment that was not lost on any of us! Perhaps one of the most historically interesting visits was a tour of the Vilna Ghetto which the Nazis had created to contain the Jewish population after the first huge group of people were killed. Many of the houses are still intact, as are some of the walls surrounding the contained community. In September 1941, after killing thousands at Paneriai and other places, the Nazis rounded up the rest of the 20,000 Jews of Vilnius and hastily sent them to the Old Jewish Quarter, letting them bring only what they could carry. Both a large and a small ghetto were established, each with distinct boundaries. Previous residents of the area were evicted, and the Jews were forced to live in crowded conditions which bred illness and despair. Forced laborers were given identification for themselves and their families with which to obtain the barest of rations; the rest had to fend for themselves. Periodically, the Nazis would weed out the ill and infirm, killing them or sending them to concentration camps in Estonia. By September 1943, the rest of the Jews there were either liquidated at Paneriai or sent to camps in occupied Poland. The ghettos still had the manhole covers from which those who hid under the streets could sometimes emerge to obtain food, or which young, militant Jews used to try to retaliate. One could still see the headquarters of the Judenrat (the organization of Jews chosen by the Nazis to administer the ghetto internally). The hospital still stood, as did many of the buildings that served as crowded homes for thousands of Jews forced to live there. The woman leading our tour had written the definitive book on the area; her knowledge was extensivewhat had occurred on every streetcornerbringing alive the awful conditions under which Jews lived there from 1941 to 1943. Another moving day was spent in Kaunas (Kovno) where we visited the Ninth Fort. Once a prison, it served as another killing place for Jews during the Holocaust. We saw beautiful art about the Holocaust there, photos of victims, descriptions of the Righteous Among the Nations who acted on behalf of Jews in Lithuania, and barracks where people were kept before being killed. The most moving part was walking the Way of Death, the path that the condemned Jews were marched along as they went to their deaths. Again, the group said Kaddish, and also viewed a rather ghoulish sculpture created by the Soviets to honor those who had been killed. The sculpture was huge, with three monoliths jutting out of the earth. One tower was to honor those who died, another those who were wounded and would die, and the third those who resisted and fought back. Garish faces and fists protruded from the sculpture, unearthly and frightening in their surrealistic angularity. Most in our group did not like it but were strangely drawn to it. That same day, the group went to the Kovno Ghetto at Slabodka. This was a rather primitive looking area, and at the time, there had been no running water. Those who survived the initial killings from July to December 1941 were rounded up and put there, some 20,000 people in all, and were forced to become laborers working for the Nazi regime. It is also said that because the Nazis would not allow babies to be born in the ghetto, many women gave their children up to Lithuanian foster mothers who were eager to take them. In all by the end, only 500 Jews survived the ghetto, many hiding in the forests when they could escape. Once again, our group was deeply saddened and touched by all that we saw. The process of traveling in Lithuania brought us to many different types of memorials. Some were stark and austere, reminding us of the Soviet style of Brutalist realism. These concrete structures, huge and mammoth, loomed over the sights we viewed. Others were simple and tasteful, like the Way of Death at the Ninth Fort, where you could feel those who had gone to their death there. These types of memorials inspired sadness and evoked the trauma that took place. Paneriai was one of those places, with the simple museum and the pits being maintained for all to see. But perhaps the most moving event and memorial on the whole trip was going to my fathers village of Kupiskis, in the northeast part of the country. On what was called a roots tour on our fourth day in Lithuania, we all set out for the regions that our ancestors had come from. Some went to Belarus, others to Latvia, and still others to different parts of Lithuania. My group set off with seven of us, a driver, and a translator in a bus for what was to become a profound experience.

YISGADAL V'YISKADASH: THE KILLING PLACE AND THE VISIT TO KUPISKIS

As we left the bus, the sky was already beginning to cloud over and look ominous. In the distance we could see a water tower the Soviets had built after they took over the country. They had also bulldozed much of the Jewish cemetery which had been there for centuries, leaving only a few remnant graves at the side of the tower. As we walked slowly, I was anxious but thrilled. I was finally coming to the place of my terrifying dreams. Would it be as I imaginedor would it be worse?

The park like setting is the killing place of the Jews of Kupsiskis and the Kupa River in the background

To the right of the hill on which the water tower stood was a sloping hill with a memorial at the top. The translator said it honored the Jews killed in this shtetl in June 1941. As she read it, I felt moved. We were finally here, and it was a beautiful place with a touching statement. The hill sloped downward into a lovely garden with steps and flowers. At the bottom of the steps was a small place to stand to look out over the field toward the Kupa River which my father had told us about. He had said that he often took Charlie, his horse, over the river from their small farm into town. I could see it all now; it was real and moving: quiet, peaceful, nothing like I had imagined in my worst daymare. As we went down the steps, the eight of us were silent, all feeling the sacredness of the place. Beneath our feet were the bodies of the 2,000 Jews killed there on a single day (more than 800 from Kupiskis and the rest from the surrounding region). My brother took out the prayer books he had so thoughtfully brought and handed them around so we all could say the Kaddish as we had intended. I wept as we recited the old, familiar words. And then the skies opened up; we were drenched with a downpour that we had not seen coming. Was our martyred family weeping with us? Was it mere coincidence? I would never know. All I knew was that we were sopping wet running for cover, since we had no umbrellas or raincoats. As we hastily climbed the steps, my brother ran to the cemetery near the water tower and said another Kaddish for our grandfather, whom we knew had been buried there. And then it was over. We sat in the bus in silence, trying to cope with the reality of what we had just seen. This was not the time to process it; that would come later. We also knew there was more to see in this shtetl, so off we went, with nary a word to mark what we had just seen or done. Earlier, when wed pulled into Kupiskis, I had to use the ladies room and asked to stop at a bus station we were passing. I paid my lita (the local currency) and used the facilities. When I came out, the attendant was screaming at the other women in our party, yelling that they had not given her enough money although theyd paid five lita for four women. Our guide dealt with her and realized that the woman could not add. Watching the comic scene, my brother and I joked that you cant piss in Kupiskis, and recalled what our father had often said: The people there are peasants, and you do not want to go there; you will not be welcome. Our introduction to the town had quickly proven him right. Kupiskis had once held 2,000 Jews, half its population. The town itself had been in existence since the 1500s, with Jews and other Lithuanians living harmoniously from the 17th century until World War II. Although there was some anti-Semitism, most residents shared a cooperative interaction for most of their lives. Jews had been farmers and producers of handicrafts. According to historical sources, there had been mills, private bakeries, and tearooms within the city. Jews were employed as shoemakers, joiners, tinsmiths, blacksmiths, hairdressers, photographers, dyers, wool combers, bakers, watchmakers, potters, and innkeepers. Many also received funds from their families abroad once emigration began in the late 1800s. Kupishok (as the Jews called it in Yiddish) had been a center of Jewish life. Jewish tradition and knowledge abounded, with everyone following the ancient tenets of the culture. In fact, it was one of the oldest Jewish settlements in Lithuania. Wary of the localsafter all, they had collaborated in the killing of our peoplethe tour group next went to where our fathers family had once lived: 52 Gedamis. It was easy to find, but the house was not there. Instead, there was a police station across the small street, a house at number 50, and an empty field. A local officer explained that the house had been torn down four years ago. Before that, it was a home for the indigent, this public use actually a consolation rather than its being taken by a private family. If I had any thoughts of seeking ownership of the family's land, once I was in that place, I realized that I did not want to own land there. The house was a mere half-mile from the killing place. As I stood there, I wondered what my aunt, uncle, and grandmother had experienced. Did they go to their deaths together? Were they separated? Were they praying? Crying? Helping each other? Being there answered some questions but raised even more. I had never had these thoughts before, but here I was now, where they had once lived. It was so real and yet equally surreal to be there. I also saw that it was a comfortable neighborhood. Homes were well-built and large, with gardens and wide distances between them. A picture from the 1920s showed a substantial house across from the city hall and prison. Our family had been well off, or at least comfortablea substantial family with hopes and a bright future. After seeing the site of the home, we went to the local library where the memorial wall we had helped construct in 2004 was housed. It was a magnificent wall done in brushed stainless steel with a gold titanium finish. The Wall has etched copy on thick laminated cherrywood panels. The three sections include the 824 names in ten similar columns. The header panel has a verse from Isaiah in Hebrew, English, and Lithuanian: I will give them an everlasting name that shall not be cut off. At the bottom of the panels were the names of those who had contributed to the memorials construction, including my brother, his wife and son, and myself and my daughter. I felt such a close connection to my family; it was here that I could see the reality of their demise. It was duly documented and honored. We lingered there for quite a while feeling the magnitude of what we were experiencing. Behind the library was the old shul, or synagogue, which had been made into a community multipurpose room. The mechitza, the womens section upstairs, had been boarded up, but otherwise it still looked like a shul. I was sure our family had prayed there. And then we were hungry. It was lunchtime, and a lovely young Lithuanian woman who had befriended us at the library walked us to an excellent local restaurant where none of us could read the menu; this is not a town to which tourists are drawn. In honor of our father, my brother and I ordered borscht with potatoes, and excellent rye bread. It was as if our father was with us; this was his favorite meal, and we fully relished it, since we were in his town eating his most adored food. In fact, it was also a bond that grew between my brother and myself, since we were the only ones at the table who knew the importance of what we were eating together. It was a touching moment. We had come full circle from the meals at our table at home, sitting with our father. Then it was over. In a matter of three short hours, we had seen it all and done what we had come to do. It was poignant but not as awful as I had expected. I knew I had a lot to think about and to make sense of, but that would come later. I had seen the killing place, the house, and the memorial wall. The family had long been dead, my father long gone from here and from the Earth. Our time in Kupiskis was over, and I needed to figure out what it all meant and how to deal with all that I had seen and done. A few days later, our journey to Lithuania ended, and I went home, still trying to discover what this whole trip had done to me. But that answer would not come until a few weeks later.

EPILOGUE

Soon after my return from Lithuania, it was my seventieth birthday. As was my ritual, I attended a meditation with a guide who helps me see where I am and where I might be heading. It is held at a rustic mountain retreat called Light on the Hill, not far from Ithaca, N.Y. There is a pond, and serene nature surrounds us; we can access places I do not go without help. I told my guide (Alice McDowell, owner of the center) about my daymare and my trip to Lithuania. As rain pelted the small hut, I was reminded of the downpour at the killing place of my family. It was a perfect setting for my attempt to make sense of my experience. Alice asked me to imagine my daymare pit and the usual falling into infinity. Naturally, I resisted such a suggestion, but I always trust her; I tried to allow myself to go where I do not generally let myself go. I fell and fell and fell, as I had in the past. In fact, I kept falling for quite a while. My daymare is so familiar it is where I always go. But finally I stopped falling. I could see a small light ahead; the infinity Id always imagined was not so infinite after all. The narrow downward spiral began to open up, and I came into the light. I was no longer in my body, but I was a spirit. The place I entered was lovely, with a bright blue sky and puffy white clouds. Alice told me that for Buddhists, the image represents Nirvana. As I exited my spiral of infinity, I was met by my old childhood friend Michael, whom I used to see sitting in the synagogue with my father and the other men. Michael died many years ago. But here he was welcoming me to this place. I did not even ask where I was. I went willingly because I trusted him. In the background I could see my mother and father, but they did not approach. Instead, Michael told me there were some people he wanted to introduce me to. I was met by my murdered ancestors. As my grandmother, Yenta Leah, my aunt Althea and uncle Hershel came toward me, they wordlessly told me that they were all right and in a good place. They said I no longer had to be the memorial candle I had been my entire life. They indicated that I had done my job, and now it was finished. Their lives had ended; they were 73 years away from the atrocities now. Their spirits were free, and mine should be as well. I realized that Altheas name meant healing, and I was about to begin my own. A great sense of relief came over me, and I felt at peace. I had done what I was supposed to do but no longer had the obligation to honor and work for justice in their names. In actuality, I had a hard time letting go of that identity, and am still not sure that I will. But I was sure that I was released from the tragedy that had plagued me for my entire life. I have been back for a while now. I have not had the daymare, nor have I been depressed by its loss. I still feel compelled to tell my family's story, but it is now a story that does have an ending. I may not fall down the pit into infinity upon my own death. My ancestors lives are remembered and honored; I will forever memorialize their stories, and will still work to stop such atrocities from ever happening again. I may not be able to, but I still feel compelled to try. It has been a life of pilgrimage, but I think the pilgrimage is over. I can now live my life free of their pain and suffering. That is a gift. from the 2015 Editions of the Jewish Magazine Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used. |

|

| All opinions expressed in all Jewish Magazine articles are those of the authors. The author accepts responsible for all copyright infrigments. |