| Â Â |

January 2015Â Â Â Â |

|

|     |  |     |      Browse our  |

| Â

Image 1. Bagnowka Cemetery. Bialystok, Poland Â

The Lions of Bagnowka:

By Heidi M. Szpek, Ph.D.

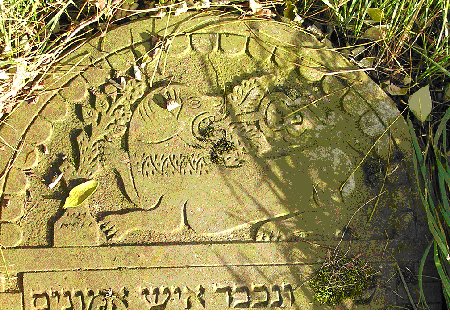

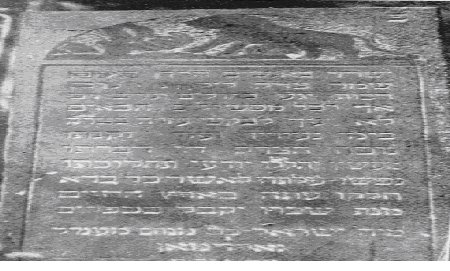

In 1912, renowned Russian and Yiddish writer and ethnographer S. An-ski, began a three-year ethnographic expedition to collect the disappearing treasures of Jewish folklore, including folk art as found in old synagogues and on tombstones. Folklore, he believed, was not only part of Jewish heritage but also the pathway to a new contemporary Jewish culture. Coterminous with S. An-skis travels, an unintentional traveler, a World War I German field rabbi, named Arthur Levy, began gathering representative examples of Jewish folk art found on tombstones throughout northeastern Poland and the adjoining areas of Belarus and Lithuania. Levy was taken by tombstone art, so extraordinary that he thought each was custom-made (p. 20). Today, little of the art they recorded remains in situ. Collections are housed, at times, in regional or national museums and preserved in publications, but more often they have been lost to time and to devastations. One repository of folk art, however, remains the Jewish cemetery, itself further decimated during the Holocaust. Yet, where still standing, each cemetery can serve as a record of Jewish folk art, influenced by regional culture but also bearing affinity with artistic culture much farther afield. At Bagnowka Beth Olam in Bialystok, Poland, a cemetery that Levy himself visited, we find one such repository of Jewish folk art that still exists today (Image 1). In use from 1892 to 1969, today less than 3000 of the possible 30-35,000 tombstones remain on this cemetery, in varying states of disarray and reconstruction. However, over 800 examples of cemetery art are still extant here, spanning nearly the entire history of this cemetery. Of these 800 examples almost 500 are classified as folk art. The term folk art, in general, refers to the art of the common folk, often of the countryside, deriving from formally untrained artisans, as opposed to the high art of a nation or culture. Executed in bas-relief of varied dimensions and depths, many of the seemingly simplistic symbols of Jewish funerary folk art in Poland, including on Bagnowka, derive from the realm of Jewish ritual. Thus, we find hands raised in priestly benediction, the Levitical pitcher, scholarly books, a charity box as well as candles and prayer books from the womans domain. From the world of fauna, lions, the classical gryphon (a lions body with a birds wings), deer and birds are also preserved. Trees, flowers, leaves and acorns are found from the world of flora, including the occasional depiction of the regional cornflower and poppy flower. From the heraldic tradition of Poland (and Europe, in general), an unadorned coat-of-arms flanked by plumes or leaves is also in evidence. However, the most prolific symbol at Bagnowka, save the Star of David and the candle, is the Lion of Judah. This majestic creature, which owes its origin in Jewish tradition to the tribe of Judahs blessing as Judah is the lions whelp (Genesis 49:9), became symbolic of all Israel and, in general, represents power. At Bagnowka, the lion appears on nearly 90 tombstones, at times, in a reclined posture; occasionally on the prowl. Most frequently, however, the lion appears in an upright or standing posture, perhaps influenced by the protective stance of the lions on the stairs of and beside the Solomonic altar (II Chron. 9:18-19). Not uncommon, two lions (or occasionally a lion and a deer) also take a heraldic stance, flanking a variety of center symbols. In this scenario, the two animals create an image-name association for the deceased or his father: the lion indicates Ari; the deer Tsvi. (Image 2)

Image 2. A lion and deer flank a poppy flower, c. 1913. Folk art need not offer every detail of its real-life counterpart that is the nature of folk art, where simplicity and generality of forms, cleansed of secondary or accidental influences mark the artists style (D. Goberman, 22-23). Among the Bagnowkas lions, we see this simplicity and generality of forms, the execution of which is not uniform throughout the history of this cemetery. Consider four of the nearly 90 extant improvisations of the lion, defending the Torah, depicted as a scholars books, all dating to c. 1900 1910. In the first two examples (Images 3 and 4), an upright lion is juxtaposed against books; each lions tail is curved upwards (though the tail tips are not identical!), with individual toes delineated. In the first, the lions tongue is extended, a typical detail; in the second, it is oddly absent. Yet, in the second, the artist precisely delineated the lions chest, allowing one hind leg to appear clearly behind the other. The lions eyes, noses and abdominal muscles are each suggested by the slightest of engraving strokes. The eyes are not identical. Each mane, too, is distinct in its execution, as each artist attempts to depict the lions thick plait. Beneath each lion, a single leaf is depicted, perhaps suggestive of life cut short or merely ornamental. Though the overall compositions are parallel in arrangement, attention to their details forces us to acknowledge these improvisations are quite distinct!

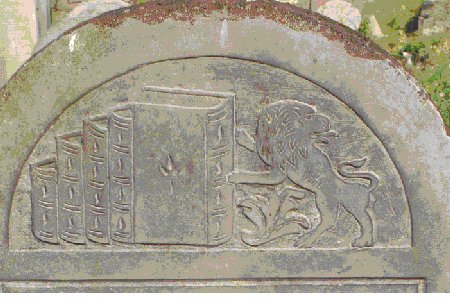

Image 3. The lion as defender of Torah, c. 1900.

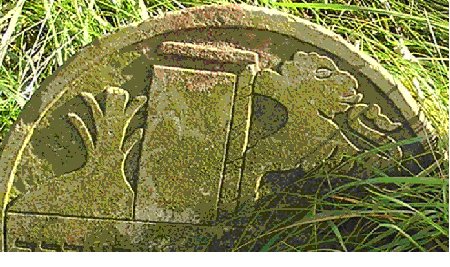

Image 4. The lion as defender of Torah, c. 1900. In the next two examples, each improvisation of the lion and book are even briefer in their execution. (Images 5 and 6) The tongues of the lion are still depicted, perhaps an attempt to visually recreate the lions roar. The abdominal muscles are pronounced but details of the mane are barely existent, save an indication of the lions neck in both and the gentle curves of the lions head in the second. Eyes and noses are indicated though in the last the nose is only in outline. Yet an ear is provided for the first! Indeed, these lions are even more removed from realism as is the nature of folk art, resembling the art of Polish and Jewish paper cuts. The compositional arrangement of these renditions is nearly identical to the first two, save the placement of the leaf now depicted as a small tree whose top is broken. The top branch (not visible in the second of this pair) is placed at right, creating a parallel composition. The meaning of this tree and perhaps the leaf in the first two improvisations is of life cut short by the power of the lion (death). A composition thought only to suggest the deceased as a defender of Torah now also comments on the frailty of life cut short by death. Reading these compositions helps us interpret the others.

Image 5. c. 1910.

Image 6. c. 1900

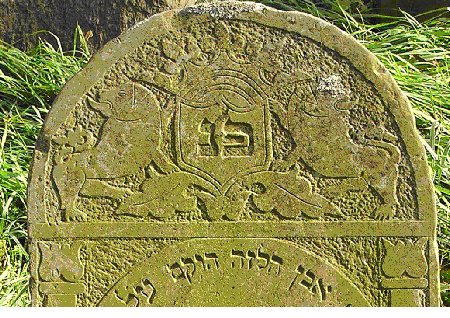

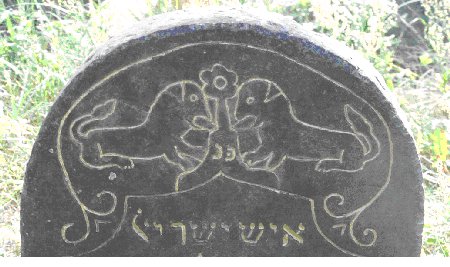

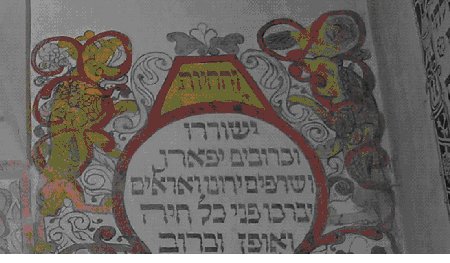

In two additional improvisations from Bagnowka, the flanking alignment of two lions around a central element create a symmetry not infrequent in folk art of the tombstone. A more refined execution (Image 7), finds two lions that scarcely resemble real-life, in keeping with the rendition we saw in Image 2. They flank a foliated shield, which holds the opening abbreviation meaning Here lies, atop which rests the crown of the Torah. In the next example (Image 8), just an outline of the lions is offered, heads turned towards the central element of a flower in bloom. The inspiration for this composition may be the heraldic coat-of-arms. Indeed, an early coat-of-arms from Bialystok is similar. Influence, however, may also derive from regional Jewish artistry, as seen, for example, in the nearby synagogue of Tykocin, which preserves an illuminated inscription with two symmetrically posed lions, with tongues extended (Image 9).

Image 7. C. 1900.

Image 8. 1898,

Image 9. Synagogue Inscription. Tykocin, Poland That historic continuity in artistic tradition prevails within Bialystok is not surprising. Indeed it is expected. In the limited extant photographic record from Bialystoks pre-19th century Jewish cemeteries, we find folk art symbols that bear affinity with those on Bagnowka today. On Bagnowka, however, there are also hints of compositional influence beyond the city and region as seen once again in improvisations of the Lion of Judah. One example of a reclining lion, extant only twice at Bagnowka (Image 10), finds a parallel in Levys collection (Image 11), in the cemetery of wita Wola, located in present-day western Belarus, 113 miles from Bialystok. In this rendition, the lions head is turned back from its body in the act of tearing a blossom from a tree. The branch is held between the lions teeth, while one front paw holds the tree from which it was torn. With this visual detail, we see an intense comment on the destructive force of death (the lion) on life. Within this blossom is the opening abbreviation. Though some details are not quite discernable in Levys photograph, preserved in the common painted rendition, it is obvious the renditions are not identical! The torn blossoms are distinct as is the framing of the ornamental register. The position of the lions back pawn is distinct in each. Yet the preponderance of leonine details, its shape and the overall compositional integrity suggests some sort of influence.

Image 10. Bagnowka. Bialystok, Poland, c. 1900.

Image 11. wita Wola, Belarus, 1909. In yet another unique rendition at Bagnowka, extant on only two matzevoth, the lion is set within a rare panorama (Image 12). The lion, teeth bared, is positioned on a hillock, facing a broken tree, suggestive of a life cut short by the power of death (lion). In a tombstone image from the Warsaw Jewish Cemetery, preserved by A. Levy (Image 13), we find a similar composition. The Warsaw panorama is painted and more formal in its execution, whereas Bagnowkas is simply etched. Nonetheless, there is clearly artistic freedom in the Bagnowka rendition though the earlier Warsaw depiction (or others no longer extant) may have served as the inspiration for Bagnowkas (c. 1910).

Image 12. Bagnowka. Bialystok, Poland, c. 1910.

Image 13. Warsaw, Poland, 1870.

That Jewish funerary art through space and time shares a repertoire of symbols has long been known. That regional culture might influence an artisans craft is likewise of no surprise. Yet Jewish folk art on the cemetery provides one venue to observe and contemplate a connection with traditions of the past, traditions of artisan craft travelling over the miles as well as through the centuries. Considering just one symbol, the Lion of Judah on Bagnowka Beth Olam, we see that its largely unknown artisans drew upon a legacy of forms and compositions, transformed by the artists imagination, an imagination fueled by regional culture, both Jewish and non-Jewish. Yet the artists influences need not be physically limited to this region, as suggested by the unique compositions found at Bagnowka, compositions which share remarkable compositional arrangement with tombstones over a hundred miles to the west and to the east. Sources and Suggested Readings: A. Kantsedikas and I. Serheyeva, Jewish Artistic Album by Semyon An-sky. Moscow, 2001. See also: An-ski Ethnographic Expedition and Museum and Rapoport, Shloyme Zaynvl. The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews of Eastern Europe. Available at: http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/ A. Levy, Jdische Grabmalkunst in Osteuropa. Berlin: Verlag Pionier, 1923. http://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/freimann/urn/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30-180014619003 D. Goberman, Carved Memories: Heritage in Stone from the Russian Jewish Pale. New York: Rizzoli, 2000. Folk Art. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/212096/folk-art Bialystok Jewish Cemeteries. Virtual Shtetl. http://www.sztetl.org.pl/en/article/bialystok/12,cemeteries/

Heidi M. Szpek, Ph.D. is Professor Emerita of Religious Studies at Central Washington University and currently an educational consultant, translator and epigrapher for Centrum Edukacji Polska-Izrael w Biaymstoku (Poland) http://bialystok.jewish.org.pl/ , working with Aktion Shnezeichen Friedensdienste (Germany) https://www.asf-ev.de/ to restore the Jewish cemetery of Bagnowka in Bialystok, Poland. In 2007, Professor Szpek conducted a survey of the cemeteries in the Grodno gubernya region of (northeast) Poland, including the largest urban cemetery of Bagnowka (Bialystok), the main focus of her subsequent research. http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/bialygen/GGPIP.htm She has contributed translations to the JewishGen Online Worldwide Burial Registry (JOWBR), examining epitaphs throughout eastern and central Europe and the Netherlands, collaborated through translation in documentation of forgotten cemeteries in northeastern Hungary, and, most recently, explored Jewish cemeteries throughout the Baltics States. She has contributed to a variety of academic journals as well as to The Jewish Magazine online. She is currently completing a manuscript on Bagnowka Jewish Cemeterys epitaphs and working on a website devoted to the Jewish epitaph www.jewishepitaphs.org Photographic Copyrights: Heidi M. Szpek and Frank J. Idzikowski. Reproductions of A. Levys photographs courtesy of the Brest-Belarus Group (www.brest-belarusgroup.org ). from the January 2015 Edition of the Jewish Magazine Material and Opinions in all Jewish Magazine articles are the sole responsibility of the author; the Jewish Magazine accepts no liability for material used. |

|

|

|  |  |

| All opinions expressed in all Jewish Magazine articles are those of the authors. The author accepts responsible for all copyright infrigments. |