|

Searching for Stanley Stein

By Jerry Klinger

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays

many parts,”

William Shakespeare – As You Like It – 2/7

“Each time someone stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of

others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope.”

Robert F. Kennedy

Stanley Stein was not his real name; it was a name he chose for himself in the few seconds he was given, rather than being known simply as patient #746. He could not use his real name anymore. He did not want the stigmatization, the fears of societal revulsion and isolation to extend to his beloved family that he had been snatched away from suddenly, traumatically. Stanley Stein was a leper. Taken away under American quarantine laws, to a benign American concentration camp in Carville, Louisiana with other diseased human beings like himself; Stanley was 31.

Stein’s real name was Sidney Maurice Levyson. He was born in Gonzalez, Texas, June 10, 1899. He grew up in the tiny hamlet of Bourne, Texas where his father opened a drug store. The Levyson’s were the only Jewish family in the community about 30 miles Northwest of San Antonio. Sidney grew up in Bourne’s intensely German community, thick with anti-Semitism. His family provided much needed services there even if they were first viewed as economic pariahs. Over time, the Levysons were accepted into the local social life and order of Bourne. Even without much in the way of formal Jewish education, Sidney always knew that he was a Jew. “Although I had been born and circumcised as a Jew, I was not hard-shelled in my Jewishness.” He was proud of his heritage as a Jew and a Texan. Sidney’s grandfather had fought for the Confederacy as a Texan.

Sidney wanted more for himself than Bourne offered. Graduating from the University of Texas with a degree in Pharmacology he opened his own drug store in San Antonio. Loosely tied to San Antonio’s reform congregation Temple Beth El, Sidney’s real pleasure was the community’s little Jewish theater. He had always wanted to be an actor. He thoroughly enjoyed being a creative person, projecting a story of fantasy unto the realty of the stage for the world to see. The irony of life was that he was to become someone else. He became not a pretend someone else, a real someone else. The someone else was to become his life. The someone else, the Jew from Bourne, Texas became, helped change the world for the better.

Sidney was only 21 when the first symptoms of Hansen’s disease (leprosy) appeared on his body. A San Antonio physician, advanced in his understanding of the seeming poor communicability of Hansen’s treated Sidney quietly. Secrecy was necessary. Unscientific medical perception was that leprosy was highly contagious. Dr. McGlasson knew from his own readings and medical experience it was not. He was proven, scientifically, correct years later. Society, reinforced by confused biblical injunctions and historical medical ignorance treated leprosy with fear, confusion, revulsion and even murder. Society protected itself from leprosy by isolating the victim. American quarantine laws required that leprosy victims be locked away without benefit of legal protest.

Sidney’s disease progressed. Dr. Mcglasson died. Not knowing the nature of Sidney’s dermatological condition, Rabbi Ephraim Frish, of San Antonio’s Beth El Congregation, recommended that specialists in New York could do better for him. Sidney could no longer hide the evidence of the visibly spreading disease. He took the advice and went to a specialist in New York.

Sidney’s life changed in the theater of New York. The specialist, Dr. Emil Loch, a renowned dermatologist, reported him to the authorities as a leper. The police swept up Sidney, almost overnight. With a small suitcase that contained his life, he was sent secretly, swiftly and with as little human contact as possible to vanish into the interior of America. He was shipped to the very isolated world of Carville, Louisiana on the banks of the Mississippi River. Carville was the continental United States concentration camp for victims of Leprosy. Standing naked before a board of medical examiners in Carville, Sidney Maurice Levyson was assigned a number that he was to be known forever more as, patient #746.

Sidney Maurice Levyson was no more. Sidney was dead to his friends, to his family. Sidney was gone, disappeared. He could choose a false name to live under if he chose. A new person, a different man, Stanley Stein, stepped unto the hot, humid, mosquito infested stage of the deep South, confused, bewildered and depressed.

Stein, years later, wrote about his first view and day at the hospital.

“Then I noticed the high metal cyclone fence with the three strands of barbed wire running along the top. I first saw the uniformed guards at the gate – and I realized that the moment I had been fighting against for nearly ten years had come at last.

I had arrived at U.S. Marine Hospital No. 66, Carville, Louisiana…. At ten o’clock on that Sunday morning, March 1, 1931, I became an exile in my own country.”

After admittance and assignment to a room in a cottage, the other patients were always curious about a new comer.

“…Five minutes later the door opened again to admit the most lugubrious character I had ever seen in my life. He announced himself as Jeremiah and the name could not have been more appropriate. He had a melancholy rabbinical air – sad, deep-set dark eyes, long side-burns that curled, a sparse black ruff of beard, a long shabby frock coat. Before the disease had struck him, he had been a Talmudic scholar in Philadelphia. He spoke with a strong foreign accent and tears in his voice, but he quizzed me with the persistence and thoroughness of a district attorney. I answered his intimate personal questions with utter frankness, for I did not know then that Jeremiah considered himself the Carville town crier and that his Winchellesque report on the latest arrival would soon be broadcast through the hospital.

‘I know I should not say that I am glad to see you here,” said Jeremiah, “but the truth is that I am. Many intelligent people to talk to, we don’t have here. There was one patient here you would have liked – smart like you, a philosopher; he knew the Pentateuch and the Talmud by heart. But we don’t have him anymore.”

This was the first heartening word I had heard all day. Then it was true that people actually did get out of Carville!

“When was he discharged?” I asked.

“Oh, he wasn’t discharged,” Jeremiah replied. “He committed suicide…”

Jeremiah’s late friend, a rabbinical student, had poisoned himself by drinking Lysol. He had died only after hours of agony. Ever since, Jeremiah told me with a macabre laugh, the patients had been calling the disinfectant “Jew wine.”

How long, I wondered, must a man cower under the humiliation of being thrust beyond the pale before he could muster the courage to destroy himself? To what depths of despair and hopelessness must he sink to prefer the slow, excruciating torture of death by Lysol? Was this a hint, on my first night at the national leprosarium, of what might be in store for me? Wasn’t it enough that I had to fight the ravages of the disease without confronting the strictures of society, emasculation of the ego, and disintegration of the soul? Was this the beginning of the end? Was there no future for me?

For hours I stared into my private wakeful darkness. It was hard for me to realize how far I had come, almost over night, from my pampered youth; the warm, wise patriarchy of my pharmacist father; the cultured aloofness of my gentle mother in the alien friendship of a first-generation German-American community of a small Texas town, with its gemutlichkeit, its Gesang Vereing, its kaffee klasch with strudel and kuchen. I found it hard to believe that I had only recently been part of a laughing, carefree group in San Antonio, a rather important part, in fact basking in the adulation of young men and women who looked up to me in the unclouded prospect of a rose colored future. I found it even harder to close my mind to the girls I had left behind – charming, eager, civilized girls to whom I was yesterday still a person. I couldn’t quite shut out the image of one girl in particular, a gay yet serious girl with tenderness and understanding in her dark eyes, a girl whom I sincerely loved yet dared not ask to marry because of the frightful secret I could not share with her, a girl whom I now knew I would never see again.

This recent past was so unreal now that the effort to connect it with my terrifying present was overpowering and I fell asleep in spite of everything.”

He would spend the rest of his life in Carville. Only in death, at long last, would he be released.

* * * * *

Sitting in teeth gnashing traffic, day by day, wasting life away commuting to the office is a mind numbing experience for most modern American workers. My experience is no different; hour after hour, morning and evening, five days a week, crawling along the freeways at the blistering average speed of 17 miles an hour, I can actually feel myself shedding life into empty uselessness. But for one discovery, commuting would result in driving insanity – recorded books. It was a discovery that changed the frustration of the drive into a welcome diversion.

The public library is a source of pure pleasure, a treasure house of books being read on tape or CD’s that I can listen to while commuting; from mind dead to alive again. My choices tend to cluster around history and this esoteric choice was no different. The Colony – the story of the leper colony on Molokai, Hawaii and Father Damien. It was tape 12 of 17 that I first heard the name, Stanley Stein. I learned how he helped change the world for the better through the “Star” as a crusading, influential newspaper editor.

Sitting in the car, even after having parked it in my space in the garage, I continued to listen transfixed about Stanley Stein, a Jew from Texas. I needed to know more. What was Carville? Why, how, I did not understand….. If I don’t know, read. If I can, go and see. I went to Carville.

A two-hour trip on a silver bird carried me to New Orleans. Courtesy of Hertz rental cars, Mapquest and a full tank of gas I drove the 71 miles to Carville which is situated about halfway between Baton Rouge and New Orleans on the banks of the Mississippi River in very thinly populated and poor Iberville parish.

The site of the Carville leprosarium is isolated, and hard to get to.

It is still surrounded by a steel cyclone fence. Gone are the barbed wire adornments to keep the inmates in. Uniformed guards still stand at the gate. Gone are all the lepers. The hospital is gone. The huge grounds with huge trees are hung with Spanish moss. The facility is a Louisiana National Guard base. Just past the guarded gate and Stanley Stein Drive behind it, on the right side, is a small off white building, the National Hansen’s Disease Museum. The covered front porch has a large silver colored, ship sized “dinner” bell off to the side. The bell was used to summon the patients to the dinning hall for meals.

Remarkable, dedicated public health research physicians, working with a plentiful volunteer human guinea pig supply of patients at Carville, discovered the efficacy of sulfone therapy in the 1940’s. It was the first miracle drug that finally could treat and defeat leprosy. Stein was a volunteer but for him it was too late. Stanley was, by then, blind, his nervous system already partially destroyed, his general health severely compromised. There would be no cure for him.

Stein refused to simply die or retreat into his own personal living death. He refused to let the disease take others into a living death quietly. Stein chose life. He chose to fight. He chose to improve the lives of all Hansen’s disease sufferers.

Stein hated the term leprosy. Instead, he called it by its proper name, Hansen’s disease. The bacterium, which caused the chronic disease, Mycobacterium leprae, was discovered in the 1873 by a brilliant Norwegian researcher – Dr. Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen.

Enlisting the support of the American Legion, a national Veterans organization, there were many American veterans at Carville, Stein created a voice for the voiceless of Hansen’s disease. He created a newspaper for Carville that grew outside of the barbed wire walls that eventually reached worldwide circulation of nearly 60,000. Stein’s positive activism linked American popular culture movie and stage stars, such as Tallulah Bankhead (Stein’s personal favorite actress and friend), to publicize and crusade for humane treatment of Hansen’s sufferers.

The “Star 66” the name of the crusading Carville newspaper he created and edited, promoted education, understanding and humanity. The important social and legal breakthroughs the Star achieved were at first simple: the ability to use a phone, write a letter home, vote, and be treated with human consideration and not as pariahs. The Star spread the word; leprosy was far less infectious than Tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases. It was scientifically safe to treat Hansen’s victims humanely in their own communities, near their families. Hansen’s was a very treatable disease. Hansen’s victims were human beings capable of normal, safe lives.

As successful as Stein was in helping eradicate millenniums of ingrained societal fear and confused biblical injunction, Hansen’s still lingers. It is not gone from contemporary minds. Friends would inquire where and what sort of adventure I was off too. My well-meaning wife would say simply “don’t ask”. There was no point in confronting them, “they would not understand” she retorted.

Other than the museum, the only other area open to visitors on the base was the cemetery. For a closed base, the only way to get to the cemetery was to drive to the back of the base about two miles away. The cemetery is well cared for; inmates from a local prison facility were mowing the grass around the graves when I arrived. In the cemetery, the impact of Carville is felt very keenly. Hansen’s sufferers rest side-by-side, people from Europe, the Far East, Latin America, Africa, Christian, Moslem, Buddhist and Jew.

Stanley is not here. The man who had done so much to change Hansen’s victim’s lives did not sleep amongst them. He like all of them, if given the ability, had always just wanted to be with his family.

Elizabeth Schexnyder, curator of the Hansen’s museum inquired on my behalf where Stanley was buried. A few weeks later and another silver bird, I went to San Antonio, Texas to lay a stone on Stanley’s grave. Bourne, where he had grown up was only 30 miles away.

San Antonio was nothing like my expectations of a small forgotten Texas city. I should have realized it - simple common sense. There was a non-stop direct flight from Baltimore to San Antonio on Southwest Airlines. The city has its own professional basketball team – the San Antonio Spurs. No backwater city has a professional team. It costs multi-millions to pay the salaries of the players.

The small-overcrowded airport opened out to a network of roads in various stages of flying overpass construction: each unfinished flying span of road connecting in the future to the interstate road system, desperately hoping to alleviate horrific traffic congestion. San Antonio, the sleepy home of the famous Alamo of Texas independence days, had exploded in the past twenty years with growth, people and disconnect to the past.

In 1855, San Antonio’s Jews purchased land for a consecrated cemetery outside of their small, dusty town on the San Antonio River. Twenty years earlier, during Mexican rule, Jews were not able to own land, even for a cemetery, in Texas. Only members of the Catholic Church could be landowners. Texas, as part of the United States, Jews and non-Catholics were no longer under such discrimination.

* * * * *

As with most Jewish communities, the first thing that Jews organized was not a synagogue but a burial society. Worship can take place at any home, in a rented room or outside under the open sky. Temple Beth El, San Antonio’s first Jewish house of worship, was organized in 1874.7

Jews are no different from other religious groups in Texas. They preferred to bury their dead in their own consecrated land. “Stanley Stein” is buried with him family in Temple Beth El’s old Palmetto Street cemetery San Antonio has grown up around and way past the cemetery a long time ago. The housing and people, in the neighborhood, are run down and poor.

Temple Beth El’s administrator told me how to find him, “go to the fourth walkway in from the street. Stop at the row where the first name is Cohen and turn right. He is buried under the name Sidney Maurice Levyson. The rows and sections are not marked. He must have been somebody” she said. “You are the second person in six months who asked about him.”

Beth El took over the original 1855 Jewish burying grounds. The cemetery contains the remains of Jews from the earliest period to about the 1960’s. Across the street, opposite the entrance to Beth El’s Cemetery, is the Agudath Israel Jewish Cemetery – a later organized, more traditional Jewish community. They chose to bury their dead nearby, not with the Reform Jewish dead.

Sidney is buried with his family in a 10’x 8’ concrete demarcated area. The memorial stones and burials all face away from the walkway, a sort of backward foot to head interment. He is buried next to his parents but nearest to his mother Fanny. His stone is a simple flat grey granite, slab, smoothed and carved, Sidney Maurice Levyson, “Stanley Stein”, with no date. It is a modest stone marker for a man who helped so many people. I put two small pebbles on his gravestone. One for myself and one for my wife who accompanied me. I said Kaddish and left for Bourne.

Thirty miles Northwest of San Antonio, along U.S. interstate 10, in Kendall, County, Texas is Bourne; Sidney’s childhood hometown.. Bourne is pronounced “Burnee”. My pronunciation was corrected on the back veranda of the 148 year old “Ye Kendall Inn.” We were sitting and visiting with two excited fundamentalist Christians, who befriended us. We shared quite a few very good cups of Starbucks coffee together talking about Israel and their love for the Jewish people. Nancy was a tour leader to Israel and had been there fourteen times. Robin, a Gospel music singer had only been there twice. Tears flowed from her eyes when we told her of my efforts to return the last descendent of Theodor Herzl, the forgotten Zionist, his grandson Stephen Norman, to be buried with his family on Mt. Herzl.

Nancy and Robin asked why we had come to Boerne. We explained we were looking to see and feel what a blind, Jewish leper from Boerne had seen and felt walking the community he had grown up in. Perhaps the timing was right. Across the street in the town park the annual Berges Fest, a festival celebrating Boerne’s German heritage was being set up. Tents, eats, displays and floats were in various stages of preparations, lined up neatly in two rows back from the Acorn bandstand near the shooting water fountain.

Our two friends had never heard of Sidney Maurice Levyson or of Stanley Stein. It had been a long time ago but they were very interested in this Jewish son of Boerne. It was a “beshert” act of God they said, that we should have met. Their love for Israel was real, open and very strong. Their anxiety for Israel and fears for the peace of Jerusalem, because of the news of the day, sadly legitimate. We spoke of our common trust and faith in God. Wishing us L’Hetraot – ‘till we meet again –we said our goodbyes. We parted with a sincere Shalom.

A few buildings were all that was left of the original Boerne. Being so close to San Antonio, Boerne had taken on a bedroom commuter feel. The huge Wal-Mart, at the exit from U.S. 10 at the turn off to the town, is a giveaway.

Our visit to find Stanley Stein in Boerne had turned into a spiritual journey linking our faiths through Israel to a common belief and trust in God. Spiritually, we knew who we were. We were comfortable as Jews in Boerne. Our new Christian friends respected us and we them because of faith; much like Sidney had, growing up here a long time ago.

Stein, the blind Jewish leper chose life. He chose to turn adversity into accomplishments dedicated to bring life, human understanding, toleration and medical attention to tens of thousands of sufferers from Hansen’s disease, worldwide.

Stein, much like the disease leprosy, which he called that “odious word,” is largely unknown anymore in the Western world. Hansen’s is easily treatable. Stein fought his crusade until his last breath in 1967.

Stein’s life mission is not complete. Much remains to be done in the rest of the world where ignorance, bigotry and oppression still exists for Hansen’s victims.

Stein wrote:

“People sometimes ask me if I have a philosophy of life. I do. I subscribe to the concept embraced by Evelyn Wells in her meaningful book, ‘Life Starts Today.’ I try and make the best of each day, not grieving over yesterday, and not being too concerned over what may happen tomorrow. To me, ‘eternity is the moment.”

“Instead of bemoaning the things that I have lost, I try to make the most of what I have left. In his essay on Compensation, Emerson says, “For everything you have missed, you have gained something else.”

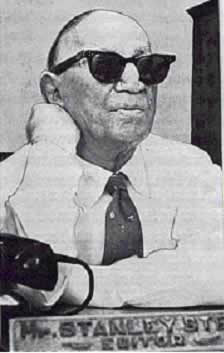

Stanley Stein's Marker

Jerry Klinger is president of The Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation.www.JASHP.org contact him at: Jashp1@msn.com

~~~~~~~

from the July 2007 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|