Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

Always Out There,

But Never Known To Me

By Elizabeth Ruderman Miller

Who were my ancestors? Where did they come from? What

were their occupations? Where is my extended family? As I

took this wondrous adventure of trying to bring my roots to

life, I realized that you can gain strength from your heritage

with the knowledge you gather each time you ‘meet’ another

ancestor or family member. We are custodians of

our family’s memories. It is our responsibility to

pass along the stories which we discover by means of the

genealogical process.

I love being a detective. Perhaps, I missed my true

calling. Then again, I may not have appreciated the process

years ago. Not having been a jig-saw puzzle fan, I may never

have enjoyed the fascination of assembling the pieces and

solving the mysteries of my genealogical hunt. When I did

become preoccupied with the search for my families, I felt

NOTHING would interfere with the discovery of clues and

evidence which would solve my family mystery.

I do, however, want to warn readers that not everyone

contacted will have the same exuberance about finding

unknown family members. Although disappointing, you

must respect their decision. At first, I found it difficult

to accept a NO. You are not going to entice everyone or

change their minds. Yes, you will have holes in your Family

Tree. It’s their loss, not yours.

I am fulfilling a dream by leading you through my

exploration to find my family members who were always out

there but never known to me until I undertook the journey

of a lifetime. In the process, I found new family friends

and the history of those whom I, unfortunately, will never

meet in person. These connections to our family I will pass

down to future generations, so that their place in our story

will not be lost again or forgotten.

When I embarked upon this genealogical quest in the

summer of 2006, I had no idea of the successes that I would

amass by 2009. I had an insatiable interest in the historical

time period of my ancestors. I know that the next time I see

‘Fiddler on The Roof’, I will view the story through more

personal eyes. Little did I dream that what I believed was a

very small ancestral line would become the extended Family

Tree which has grown and continues to flourish with each

new generation.

Shtetl Life

A shtetl was typically a small city, village or town with

a large Jewish community which was located largely in

Eastern Europe. Shtetls were primarily found in the 19th

century Russian Empire’s restricted Pale of Settlement and

in the Kingdom of Poland. It was in these villages, now lost

to history, that the remarkable culture of the Ashkenazi Jews

flourished until its demise during World War II.

Most residents were poor, superstitious and resistant to

change. They followed Orthodox Judaism despite outside

influence. Their Yiddish language became synonymous

with the Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern European shtetls.

Many of our thoughts invariably drift to scenes from

“Fiddler on the Roof” as the quintessential story of life in a

19th or early 20th century shtetl. While there was music and

dancing, the townspeople were tailors, butchers, fishmongers,

shopkeepers, peddlers and dairymen, who worked long, hard

days just to sustain their poor lives. Each shtetl was led by a

Rabbi who was respected by all Jews in the community.

Shtetls operated on the idea that giving to the needy

was not only to be admired, but was essential and expected.

The problems of those who needed help were accepted as a

responsibility both of the community and of the individual…

on earth, the prestige value of good deeds is second only

to that of LEARNING. The rewards for benefaction are

manifold and are to be reaped both in this life and in the

life to come.

As summarized in “Pirkei Avot” by Shimon HaTzaddik’s

‘three pillars’: on three things the world stands. On Torah,

on service (of God) and on the acts of human kindness.

It is this Tzedaka or charity that remains a key element of

Jewish culture.

While wealth was a secondary status, learning and

education were the ultimate measures of worth in the shtetl.

A hard working person was admired in the community, but

he who studied was considered most valuable of all.

My Ruderman ancestors resided in Kraysk or Kraisk

– now part of Belarus, then it was in Lithuania. With a

mere seven hundred residents, this was certainly one of the

smallest of the shtetls recorded in the First All Russian

Census of 1897. There are few records in existence for

Kraisk, none the less, I do hope one day to discover my

great grandfather’s occupation. I would assume, however,

that he may have been a butcher, farmer or dairyman, as my

grandfather was a butcher for most of his life in America.

On the other hand, the Bornstein and Hiller families

lived in the larger, more thriving community of Gritse,

today’s Grojec, Poland. Thanks to the stories left by my

grandmother, Annie, and grandfather, Sam, I have a clearer

picture of the lives they led in Gritse.

Bornstein Brothers Passport Picture 1920

Grandma Annie (Chana Yetta) and her mother, Bubba

(Grandma)Dina Borensztejn were skilled with a needle and

thread. They created beautiful table cloths, towels, and the

like. Grandma Annie told stories of how she and her mother

had a ‘push cart’ which they took from town to town, and

from which they sold their wares. Grandpa Sam Hiller’s

brother became an expert leather craftsman, carving saddles

and other leather objects.

It was Grandpa Sam, along with Grandma Annie’s

brother, Abe (Abram) who aspired to become scholars. I

know that my grandfather would have loved to become a

Rabbi, spending his days debating the aspects of the Torah

and the Talmud. When Sam and Abe fled the horrors of the

pogroms in Russia and Poland, they knew they would need

a skill in order to survive in their newly adopted country. I

remember when I was a child how Grandpa Sam continued

to visit the Synagogue in Paterson, New Jersey several times

per week to pray and study with other immigrants.

“Gone now are those little towns, where the

shoemaker was a poet, the watchmaker a

philosopher, the barber a troubadour. Gone

now are those little towns where the wind joined

Biblical songs with Polish tunes and Slavic rue,

Where old Jews in orchards in the Shade of

cherry trees lamented for the holy walls of

Jerusalem. Gone now are those little towns,

through the poetic mists, the moons, winds,

ponds and the stars above them have recorded

in the blood of centuries the tragic tales, the

histories of the two saddest nations on earth.”

—Antoni Sionimshi,

“Elegy for the Jewish Villages”

Grojec, Poland

Grojec (Gritse in Yiddish) is a small town in Poland. Jews

were permitted, to reside there and were recorded as early

as the census in 1754. The Jewish community numbered

1,719 in 1856 (68% of the total population), 3,737 in

1897(61% of the total population) and 4922 in 1921 (56%

of the population). On the eve of World War II there were

approximately 5,200 Jews living in Grojec.

Holocaust Period

With the entry of the German army on September 8,

1939, terrorization of the Jewish population commenced.

On September 12, 1939, all men between the ages of fifteen

and fifty-five were forced to assemble at the market, and

from there marched on foot to Rawa Mazowiecka, about

thirty-seven miles away. Many were shot on the way.

During the spring of 1940, about five hundred Jews from

Lodz and the vicinity were forced to settle in Grojec. A

ghetto was established in July, 1940, and the plight of the

Jewish inhabitants drastically deteriorated. They suffered

from hunger, epidemics and the lack of fuel during the

winter of 1940-41. About one thousand Jews from nearby

locations were brought to the Grojec ghetto that January.

On February 23 and 24, 1941, about 2,700 of the Jews in

Grojec were deported to the Warsaw Ghetto, where they

shared the fate of Warsaw Jewry. The Grojec ghetto was

liquidated in September, 1942. About 3000 surviving

Jewish inmates were deported to Bialobrzegi (a small town

on the Warsaw-Radom highway), and from there were all

sent to the Treblinka death camp. In Grojec itself, only three

hundred Jews remained, 83 of whom were deported after

some time to a slave labor camp in Russia near Smolensk,

where almost all were murdered. The last two hundred Jews

were executed in the summer of 1943 in a forest near Gora

Kalwaria. After the war, the Jewish community in Grojec

was not reconstituted. Organizations of former Jewish

residents of Grojec were established in Israel, France, the

U.S., Canada and Argentina.

Hiller Siblings

Only one of my mother’s cousins survived the death

camps during the Holocaust. After the liberation of

Buchenwald, seventeen year old Benjamin Hiller came to

the United States to his uncle, my grandfather, Samuel

Hiller.

Grysk, Kriesk, Kraisk?

GOOGLE is a wonderful tool, but doesn’t do the

trick all of the time. In the case of trying to find my

paternal grandparents’ shtetl (the Russian village in which

they had lived), I couldn’t find anything resembling the

spelling Grysk, which appeared on my Grandfather Morris

Ruderman’s Declaration of Intention for

Immigration. Trying JEWISHGEN.ORG, I was able

to conduct a search for a surname or search

for a town. I revisited the JEWISHGEN.ORG website

countless times during my three year search. For Jewish

genealogical research, it is invaluable.

Grysk turned out to be Kraysk, which was the spelling

of the tiny shtetl (village) formerly in the Uyzed (district)of

Vileika in the Gubernia (province) of Vilna which in the days

of the 19th century was part of Lithuania. Prior to 1842,

the Vileika District belonged to the Minsk Gubernia. Since

World War I, the spelling of the village is primarily seen as

KRAISK, and now is part of the province of Byelorussia in

what is now Belarus.

I began with the understanding that the Ruderman

family lived near Minsk. KRAISK is much closer to the city

of Vilna/Vilnius, which had a thriving Jewish community,

and was often known as ‘the Venice of Eastern Europe’. At

the first all-Russian census of 1897, Kraysk had a population

of under 700, with slightly over 500 Jews. Joel Ratner,

Vilna District Research Coordinator for JEWISHGEN.

ORG answered my email with a statistical analysis of all

towns in the Vileika Districk with a population in excess

of 500 person for year. The book from which this extract

was taken was originally published in French, and the shtetl

appeared as Bourgade Kraisk.

January 2008 was the month in which I would contact

a Russian man who would provide many answers about

our family’s little shtetl of Kraisk. After discovering the

Jewish Heritage Research Group of Belarus

online, I began corresponding with its director, Yuri Dorn.

His email, dated January 20, 2008 thanked me for making

the contact and explained that his organization was, indeed,

familiar with Kraisk. Just months before my first note, the

local authorities of Kraisk built a new road through the

town. Unfortunately, the road was too close to the old Jewish

cemetery, which was located on a hill. After completing the

road construction, the cemetery began to slide down the hill.

Yuri added, “One person who merely drove by noticed this

and called us. We went there right away to investigate the

situation. What we saw was a gravestone already laying on

the road. We counted 48 tombstones in that cemetery.”

This disturbing news was intensified after a response

from a considerate Russian woman named Tatiana, whose

grandmother appears to be the only Jew residing in Kraisk.

Tatiana forwarded three pictures of the Kraisk cemetery,

including that of an exposed human skull in desperate need

of reburying.

Tatianas picture from Kraisk cemetery

It was obvious that this was one of the hundreds or

thousands of Jewish cemeteries which were in desperate need

of repair. Yuri noted that the majority of Jewish records for

Kraisk are prior to 1858 and that there were only random

records after that date, among which are: a revision(census

list) from 1874 and 1886; a list of male conscripts (draftees)

during 1862-1889; a list of tax papers from the latter part

of the 19th century and some foreign passport applications

from 1898-1905. It was during the years when the Russian

Czar allowed Jews in the country. Later, in 1836 Jews were

allowed to purchase land. According to census records, the

population consisted of 100% Jews at that time. The main

occupation of Jews of Kraisk was agricultural rural settlement

which was part Of the Vilna Gubernia. Unfortunately, there

are no formal records to tell the history of this shtetl.

Returning to JEWISHGEN.ORG and performing a

town search for the shtetl, Kraisk in Belarus, I retrieved six

researchers who were interested in the same community. This

didn’t appeared very promising. Six researchers represented

only ten surnames, none of which were my last name of

Ruderman or Cohen. I emailed each one of them and

received a note from all but one. Low and behold, the

person who was looking for a Ruderman in Port Jervis, New

York also appeared on this list from Kraysk, looking for the

surname, KASDIN, which was unfamiliar to me.

Israel Connection

In the mid 1960’s, our family had a visit from Tuvia

Hofnung, mom’s cousin from Israel. He spoke very broken

English with a heavy accent, and I recall being aggravated

by his personal campaign to encourage all American Jews to

live in Israel. I was a teenager looking forward to my college

years, and I had no designs on traveling out of the country

yet, let alone volunteering in the Israeli Army.

Following the death of my Dad in 1983, I agreed to

accompany my Mom on a two week visit to England and

Israel. My insatiable interest in ancient history had not yet

evolved. Since I had been a Theatre Arts major in college, I was

more interested in seeing some British theatre productions.

Not only were we to visit our Israeli relatives, but we

would spend time with old family friends from Pennsylvania,

who were raising their Orthodox family in Jerusalem. I was

fascinated as I compared and contrasted the religious vs.

Zionistic views of this tiny country which was so often the

center of contention regarding world peace.

I had seen pictures of my twin cousins, who were the

daughters of Tuvia and his wife, Yaffa. Ora and Sarah were

a few years older than I – both were married and also raising

young families. Regardless of their very limited knowledge

of English, their children were learning the language in

school and assisted us with Hebrew/English translations

during our conversations. We ‘broke bread’ with our family

at their home in Tivon, and it was on that evening that I

learned about Tuvia’s connection with the fight for the State

of Israel, his earliest journey to Palestine and the fate of his

family in Poland.

Sarah Borensztejn, sister of Chana Yetta, Ruchel and

Abram Borensztejn, married Arie Hofnung and lived in the

shtetl of Gritse, Poland. The surviving Borensztejns, children

of my great grandparents, Dina and Tuvia, remained a

close-knit group even after immigration or deaths, (as was

the case of several sets of twins, stories told to me during

my youth by my Grandma Annie); most probably, my

twin cousin, Sarah was named for her grandmother, Sarah,

following Jewish tradition.

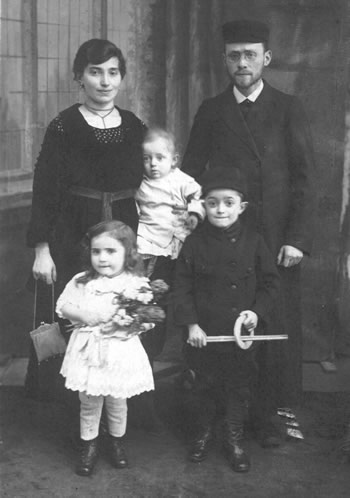

Arie, Sarah Hofnung with children Tzira, Menachem and Tuvia

Sarah and Arie Hofnung had four children. At fifteen,

looking to escape the atrocities in Poland, their son, Tuvia

journeyed to Palestine. After his initial stay, he returned

home to encourage his parents to bring his siblings to the

Holy Land. When they agreed to join him, Tuvia traveled

back to his newly adopted home. I couldn’t help the feeling

of intense pride and gratitude which I felt for Tuvia, when

I learned that he had been a brave member of the Haganah,

the underground military organization prior to the

establishment of a Jewish homeland. Tuvia fought beside

the likes of David Ben-Gurion for the statehood of Israel. I

did find it a bit odd, however, that at the dinner table, along

with Tuvia, Yaff a, their children and grandchildren, was

his former girlfriend and compatriot who had shared many

of the war experiences, nodding her head in affirmation

as the stories unfolded. When I chose to question certain

specifics about his experience during this turbulent time,

I was informed that certain information was better left

unsaid. This type of secrecy is perhaps why the Israeli

intelligence has such a worldwide reputation.

The Haganah was founded in June 1920 in Eretz Yisrael

(the Jewish homeland to be established in the general area of

Palestine) as an independent defense force completely free of

British authority. In the beginning, the Haganah defended

larger towns and settlement. After the Arab riots of 1929,

the design status of the Haganah changed dramatically.

It became a large organization encompassing nearly all

youth and adults in the settlements as well as several

thousand members from each of the cities. It initiated a

comprehensive training program for its members and ran

officers’ training courses. The Haganah established central

arms depots into which a continuous stream of light arms

fl owed from Europe while simultaneously, laying the basis

for the underground production of arms.

As a result of the British government’s Anti-Zionist

policy, the Haganah supported illegal immigration and

organized demonstrations against the British policy.

After the outbreak of World War II, the Haganah did

head a movement of volunteers from which units were

formed to serve in the British army. It cooperated with

the British intelligence, sending members on commando

missions in the Middle East. Jewish parachutists dropped

behind enemy lines in 1943-44. All the while, the Haganah

further strengthened its independence by instituting basic

training for the country’s youth. Haganah branches were

established at Jewish displaced person camps throughout

Europe. Members accompanied the ‘illegal’ immigrant

boats. During the spring of 1947, with the preparation for

an impending Arab attack, David Ben-Gurion took it upon

himself to direct the Haganah general policy. Finally, on

May 26, 1948, the provisional government of Israel decided

to transform the Haganah into the regular army which is

today the Israel Defense Forces.

The German army overtook Gritse on September 12,

1939. One of Grandpa Sam Hiller’s nephews was the first

person shot and killed while he was crossing the street.

This was verified by my cousin, Benjamin who was the

only member of either side of my family to survive the

Holocaust.

Sadly, the Hofnung family was unable to depart Poland

before their capture by the Germans. It’s unclear as to the

year of Sarah Borensztejn Hofnung’s death, but I suspect

that she died prior to her family’s apprehension. This

deduction is based on my discovery of THE PAGES OF

TESTIMONY, records located in the Central Database of

Shoah Victims’ Names at YAD VASHEM, in Israel. In

memory of his family who were murdered in the Shoah

(Holocaust), Tuvia had submitted four pages – one each

for his father, Arie, his brothers, Moshe (born 1913)

and Menakham (born 1926) and his sister, Tzira (born

1916). The material does not include the year of and place

of death, and my suspicion is that either Tuvia did not have

that information, or perhaps the Hofnung family lost their

lives from hunger or an epidemic in the Grojec ghetto.

After Tuvia Hofnung’s death, Mom had been out of touch

with his family in Israel. Through The JewishGen Family

Finder, I visited the page looking for any researchers who

were interested in the town of Grojec, the Polish spelling for

Gritse. I sent several emails to people in Argentina, Germany,

France, Canada and received the following uplifting

“Liz Shalom:

I found your family in Tivon. They were very

happy to hear from you. They promise me

to contact you. I spoke with Ora… one of

the twin girls. (supplied address and phone

number) Good luck, and I was happy to

help you. By the way, we may have a family

connection? I see you married a Miller. With

my best regards.

B. Miller

Haifa – Israel

The following morning, I received an email from Ora’s

children whom I had met in the mid 1980’s with my Mom.

Anat and Ran were now both married with children. We

continue to chat via email and telephone. Anat became

my family genealogist, supplying me with the entire Israeli

family Tree, which, I’m happy to say, continues to thrive.

From Elizabeth Ruderman Miller's new release, How Will I Know Where I'm Going, If I Don't Know Where I've Been? For more information visit: www.howwilliknow.com

~~~~~~~

from the April 2010 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|