|

Reverend William H. Hechler - The Christian minister who legitimized Theodor Herzl

By Jerry Klinger

“Political Zionism, and the modern state of Israel, was largely born from the fierce will of Theodor Herzl. Were it not for a Christian, Herzl would have remained an eccentric, obscure Austrian writer, long forgotten by now. It is Rev. Hechler, and the Zionist debt to him, that is forgotten.”

“I said to him: (Theodor Herzl to Rev. William Hechler) I must put myself into direct and publicly known relations with a responsible or non responsible ruler – that is, with a minister of state or a prince.

Then the Jews will believe in me and follow me.

The most suitable personage would be the German Kaiser.”

“One of the most important results, if not the most important, of the Kaiser’s visit to Palestine is the immense impetus it has given to Zionism, the movement for the return of the Jews to Palestine. The gain to this cause is the greater since it is immediate, but perhaps more important still, is the wide political influence which this Imperial action is like to have.”

“In the arena of leadership, perception can be defined as the acute awareness of a leader's effectiveness in an organization, based on an introspective assessment and accurate internal and external feedback”.

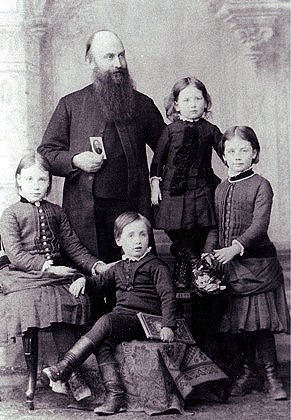

William Henry Hechler was born, January 10, 1845, in the Hindu “Holy” city of Benares, India, to a German Anglican missionary father, Dietrich Hechler, and his English wife, Catherine Clive Palmer. William’s conservative education exposed him to Evangelical Restorationism. A central belief of Restorationism was that the “Second Coming of Jesus” would occur after the Jews were restored to Palestine. Hechler’s faith did not mandate that the Jews had to convert before Restoration. It did lead him to a sincere interest in the welfare of Jews, Jewish concerns and in Palestine. Deeply distressed by Tsarist oppression of the Jews in the 1880’s, Hechler traveled into the Russian Pale of Settlement. In Russia, he met Leon Pinsker, the author of the early Zionist tract, Auto-Emancipation, which called for Jewish national separatism as a solution to the Jewish problem. 1893, Hechler self published his own broadsheet, The Restoration of the Jews to Palestine according to the Prophecy. Hechler had projected that the days of the Jewish salvation would begin in 1897-1898.

William Hechler was a volunteer German chaplain during the Franco-German war of 1870-71. He was twice decorated which put him in good regard for a position as the personal tutor to the son of Frederick I, the Grand Duke of Baden. Hechler became a close personal friend of the Grand Duke. It would be relationship that would prove crucial to Zionism.

Hechler, viewed as a pietistic eccentric by some because of his strong efforts for the Jews, engaged in a common eschatological (end of times) calculation. He studied the Bible diligently and projected a date when the return of Jesus would begin. His calculations suggested that the beginning of the Christian Messianic age would commence around 1897-1898.

Theodor Herzl was born in Budapest, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1860. He grew up in an assimilated Jewish household that had very little to do with Jewish life. He was Jewish only to the extent that he was identified as a Jew by others. Moving to Vienna, Herzl earned a Doctor of Law degree. He was never happy, nor successful as a lawyer. Changing the direction of his life, he married the daughter of a wealthy Jewish businessman, obtaining a very large dowry in the process, becoming a modestly successful comedic playwright and producer in Vienna. Herzl learned how to produce an effect on an audience by shaping the character in the play. He learned staging, the importance of props, atmosphere and dramatic impact to shape perceived reality. Branching out as a writer, he became a featured columnist for the largest, the most influential, widely read and liberal newspaper in Austria, if not in all the German speaking lands, the Neue Freie Presse.

Late 19th century Austria and Germany were the leading advanced European nations in science, the arts, culture and economics. They were also the leading nations developing and embedding advanced forms of anti-Semitism. Austro-Germanic anti-Semitism incorporated Darwinian eugenic theories. Eugenic racial theories, first developed in England, quickly spread to America and then to Austria and Germany. Eugenic theory was rejected in America and Britain. Racial or scientific anti-Semitism blossomed in the richly manured lands of Germany and Austria.

Reluctantly Herzl, the most assimilated of assimilated Austrian Jews was forced to confront the reality of the Jewish Question. He wanted to solve it, to end the hatred it represented. Herzl wanted to solve it as part of German culture. He considered mass conversion of the Jews as a solution. He abandoned that approach and kept to his marginal identity as a Jew as he lit his family Christmas tree with his children. Herzl’s progress to his solution to the Jewish Question was not a purposeful one. His answer developed slowly at first but was ultimately forced upon him.

Herzl was asked to go to Paris as the Neue Freie Presse’s correspondent for the Dreyfus trial. It was in Paris that the full realization of who he was emerged. His son Hans, many years later described a similar understanding in his own death note before committing suicide, a Jew, is a Jew, is a Jew. Herzl recoiled in Paris, how in the center of liberal Europe, France reverted to medieval anti-Semitism. Blood cries, Death to the Jews, forced Herzl to order his thoughts. If anti-Semitism was endemic, almost genetic in character and could not be remedied by assimilation, there had to be another solution he realized.

Herzl’s solution to the Jewish problem was not an epiphany born in lightning. It was a process, a cathartic process of painful internal turmoil. For months he had struggled with his thoughts. Naively, he carried his ideas to the powerful leaders of Jewry, the “Court Jews” of his age. He roughly outlined what would become his famous book “the Jewish State” to Baron Edmond de Hirsch. He approached the Rothschilds. Herzl’s solution to the Jewish Question was not assimilation but a national rebirth in a Jewish national home. The solution to the Jewish Question was political. His answer was an independent Jewish state.

Herzl revealed, in his diaries, his inner thoughts. Meeting with Baron Maurice de Hirsch, June 2, 1895. He told the Baron directly, “I shall go to the German Kaiser: he will understand me… I shall say: Let our people go! We are strangers here; we are not permitted to assimilate with the people, nor are we able to do so. Let us go!”

Herzl ideas were not received well by the titans of Jewry. He believed the path to the Jewish State was through the powerful few Jews of Europe and Turkey and more so, the enormous power of the non-Jews. Herzl never fully comprehended that the State could not be legislated or created by fiat. It could only come through the will of the Jewish people.

Fired with the missionary zeal of discovered faith, ideas he mistakenly believed were his, dramatic, unique and original, Herzl traveled to England, late in November, 1895. In Paris he had befriended the Jewish atheist and writer Max Nordau. Nordau had arrived at a similar conclusion independently as Herzl. Nordau was also horrified, observed the degradation of Dreyfus and of France. In later years, Nordau was second only to Herzl in the Zionist movement. Nordau gave Herzl key introductions to British Jewish society and to the leading writer of British Jewry, Israel Zangwill. Zangwill furthered Herzl on with introductions to Colonel Goldsmid, the real life surrogate of George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, who was influential with the Maccabean Society in England. The Maccabeans had been engaged in Zionist agricultural resettlement efforts of Jews in Palestine for years. Herzl was received well as thinker. He was an Austrian curiosity.

Herzl left more determined than ever to expand the reach of his ideas. In Vienna, his newspaper refused to be involved. Herzl refined and completed his work, Der Judenstaadt, then searched for a publisher. No one wanted to touch the work. It was radical, it was controversial. Mid February, the work was published by a Christian publisher who was having second thoughts about the undertaking. He honored his commitment and published what turned out to be Herzl’s opus magnum, February, 1896.

Few books, Der Judenstaadt was barely more than a long booklet, have shaken the world as has Der Judenstaadt. It was an instant, enormous success, selling out quickly. Herzl had hit a very, very exposed nerve in Jewish life. He was vilified, he was despised, rejected. He was hailed as a visionary, a new Messiah.

Jews were terrified by the book. Barely having been emancipated and admitted as citizens of the Western European countries they had lived in for hundreds, if not for thousands of years, (Jews first came to France, Italy, Britain, and Spain with the Romans suffering periodic expulsions and returns) Jews were shatteringly insecure. They feared the guaranteed ritual anti-Semitic accusals of dual loyalty, being fifth columnists, unpatriotic, international conspirators of world domination through Jewish cabals. Rabbinic Judaism railed against the rejection of God centered liberation. Der Judenstaadt was a call to life for the hundreds of thousands of Eastern European Jews who had recently flooded into Western Europe and the millions still trapped in Russia. They were unassimilated and, in the eyes of many Western Jews and non Jews, not able to be assimilated. The masses of refugees did not have to integrate within Christian solutions again but thought in terms of their own home. If Christian lands did not want Jews, then they would solve theirs and their own problem with their own home. The idea, electrically, leaped across the Atlantic, around the world creating heated controversy and insecurity for many Jews. Herzl was at the center of the firestorm. He was at the center and with no organization. The tiny fragmented Zionist groups around Europe slowly, then with accelerating speed, responded to Herzl.

S.R. Landau, a Zionist writer and leader came to Herzl in February, shortly after Der Judenstaadt was published, and offered his services. He made a proposal to Herzl. “Dr. Landau proposed to me the creating of a weekly paper for the movement. It is a good idea and I will go into it; the weekly would serve as my public medium.” Herzl understood marketing. He understood he needed to get his message out; he needed to publically shape political opinion. Herzl needed to reach the ears of power. Landau headed the Die Welt, the Zionist newspaper that Herzl founded. The Jewish moneyed powers had already rejected Herzl. De Hirsch was interested but not involved. The Rothschilds viewed Herzl and his ideas as dangerous. Herzl needed to get to the decision makers in the Europe. He needed to get to the European aristocracy, to the princes of power. He had no clue how to do it.

Landau separated from Herzl after a few years because of philosophical differences. He vanished in history, dying in obscurity in New York in 1943. Landau may have vanished from the pantheon of Zionist history and influence but he did do something for Herzl that should have prominently kept his name in the pages of every Zionist history book. Streets should have been named for him in every Israeli city.

Herzl recorded in his diary that Landau introduced Count Phillip Michael von Nevlinski, to him. “Landau had another good idea. Nevlinksi, the publisher of the “Correspondence de l’Est,” is on friendly terms with the Sultan (of Turkey). He might be able – in return for baksheesh – to procure for us a status of sovereignty.

Herzl’s overly cynical observation was only partly accurate. Nevlinski did manage to get Herzl a meeting with the Grand Vizier of Turkey in Constantinople in June 1896. Herzl was introduced as a representative of the Neue Freie Presse. Herzl presented his idea that the Jews would absorb the Turkish debt and provide an annual payment to the Sultan in return for a national home under the Sultan. Herzl’s walked away with a ceremonial medal, his only positive result.

It is not known for sure if Landau provided Herzl with the keys to the kingdom of public relations legitimacy by introducing Rev. William Hechler to Herzl or not. Landau certainly understood what the importance of a Christian’s endorsement of Zionism could mean. As editor of Herzl’s Die Welt, Landau published a full interview with Hechler in the second issue of the paper, June 11, 1897, Christians about the Jewish Question. Hechler introduced Zionist readers to Christian Restorationism.

Herzl’s diaries are silent if Landau introduced Hechler to him. Franz Kolber, the famous Czechoslovakian historian, says he did. Every Zionist historian has a creative literary catalyst linking the two men. Most write that Hechler, browsing the bookstalls of his favorite stores, happened upon Herzl’s book in a mysterious direction of fate.

Whether Hechler was given a copy of Herzl’s Der Judenstaadt in early March 1896, or came across it by accident, Hechler’s response changed the course of history, of Zionism and Herzl’s place in the story of the creation of modern Israel.

March 10, 1896, Herzl recorded in his diary his “first” meeting with Reverend Hechler.

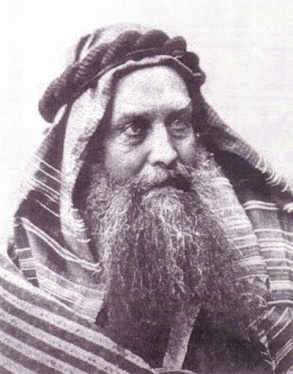

“The Rev. William H. Hechler, chaplain to the British Embassy in Vienna, called on me.

A likeable, sensitive man with the long grey beard of a prophet. He waxed enthusiastic over my solution. He, too, regard my movement as a “prophetic crisis” – one he foretold two years ago. For he had calculated in accordance with a prophecy dating from Omar’s reign (637-638) that after 42 prophetical months, that is, 1,260 years, Palestine would be restored to the Jews. This would make it 1897-1898.

When he read my book, he immediately hurried to Ambassador Monson (British Ambassador in Vienna) and told him: the fore-ordained movement is here!

Hechler declares my movement to be a “Biblical” one, even though I proceed rationally in all points.

He wants to place my tract in the hands of some German princes. He used to be a tutor in the household of the Grand Duke of Baden, he knows the German Kaiser and thinks he can get me an audience.”

Less than a week later, Herzl went to see Hechler.

“Yesterday, Sunday afternoon, I visited the Rev. Hechler. Next to Colonel Goldsmid, he is the most unusual person I have met in this movement so far. He lives on the fourth floor; his windows overlook the Schillerplatz. Even while I was going up the stairs I heard the sound of an organ. The room which I entered was lined with books on every side, floor to ceiling.

Nothing but Bibles.

A window of the very bright room was open, letting in the cool spring air, and Mr. Hechler showed me his Biblical treasures. Then he spread out before me his chart of comparative history, and finally a map of Palestine. It is a large military staff map in four sheets which, when laid out, covered the entire floor.

“We have prepared the ground for you!” Hechler said triumphantly.

He showed me where, according to his calculations, our new Temple must be located: in Bethel! Because that is the center of the country. He also showed me the models of the ancient Temple.

At this point we were interrupted by the visit of two English ladies to whom he had showed his Bibles, souvenirs, maps, etc.

After the boring interruption he sang and played for me on the organ a Zionist song of his composition. From the woman who gives me English lessons I had l heard that Hechler was a hypocrite. (a pun in the diary – the German for hypocrite is Heuchler) But I take him for a naïve visionary with a collector’s enthusiasm, and I particularly felt it when he sang his songs to me.”

In his diary, Herzl records his true motivation for coming to see Hechler.

“Next we came to the heart of the business. I said to him: (Theodor Herzl to Rev. William Hechler) I must put myself into direct and publicly known relations with a responsible or non responsible rule – that is, with a minister of state or a prince.

Then the Jews will believe in me and follow me. The most suitable personage would be the German Kaiser. But I must have help if I am to carry out the task. Hitherto I have had nothing but obstacles to combat, and they are eating my strength.”

Hechler immediately declared that he was ready to go to Berlin and speak with the Court Chaplain as well as with Prince Gunther and Prince Heinrich. Would I be willing to give him the travel expenses?

Of course I promised them to him at once. They will come to a few hundred guilders, certainly a considerable sacrifice in my circumstances. But I am willing to risk it on the prospect of speaking with the Kaiser.

But even if he is granted an audience, I have no idea of how he will strike these princely families. Actually, here is a major enigma in my path. My previous experience tells me that highly placed persons do not reason any more broadly or see any more clearly than do the rest of us. It is therefore quite as likely that the German princes will laugh at this old tutor for his collector’s quirks as that they will go along with his naïve fancies. The question now is this: when he comes to Berlin, will they pat him on the shoulder ironically and say, “Hechler, old man, don’t let the Jew get you all steamed up?” Or will he stir them? I any case, I shall take the precaution of impressing upon him that he must not say he “came at Herzl’s behest.”

He is an improbable figure when looked at through the quizzical eyes of a Viennese Jewish journalist. But I have to imagine that those who are antithetical to us in every way view him quite differently. So I am sending him to Berlin with the mental reservation that I am not his dupe if he merely wants to take a trip at my expense.

To be sure, I think I detect from certain signs that he is a believer in the prophets. He said, for example, “I have only one scruple: namely, that we must not contribute anything to the fulfillment of the prophecy. But even this scruple is dispelled, for you began your work without me and would complete it without me.”

On the other hand, if he only faked these signs which have made me believe in him, he will all the more be a fine instrument for my purposes.

He considers our departure for Jerusalem to be quite imminent and showed me the coat pocket in which he will carry his big map of Palestine when we shall be riding around the Holy Land together. That was his most ingenious and most convincing touch yesterday.”

Hechler began thinking and planning how he would gain access to the Kaiser for Herzl. He travels to Berlin on Herzl’s behest but is unable to reach the Kaiser.

Herzl’s diaries continue.

“April 16

The English clergyman Hechler came to me in the afternoon in a state of great excitement. He had been to the Burg, where the German Kaiser arrived today, and spoke to Dryander, the General Superintendent, and another gentleman from the Kaiser’s retinue. He strolled through the city with them for two hours and told them the contents of my pamphlet, which greatly surprised them.

He told them the time had come ‘to fulfill prophecy.’

Now he wants me to join him tomorrow morning on a trip to Karlsruhe to see the Grand Duke; this is where the German Kaiser is going tomorrow evening. We would beat him there by half a day. It was Hechler’s idea to call on the Grand Duke first thing, tell him what it was all about, and say that he had brought me to Karlsruhe against my will, so that I might give the gentlemen further information.

I declined to go along because it would make me look like an adventurer. If then Their Highnesses did not feel inclined to admit me, I would be standing in the street in an undignified posture. I told him to go there by himself, and if they wanted to speak to me, I would immediately follow a wired invitation.

Hechler asked me for my photograph in order to show it to the gentlemen; he apparently thinks that they would picture me as a “shabby Jew.” I promised to give him a photo tomorrow. Strange that I should just have had my picture taken – something that had not occurred to me in years – for my father’s birthday today.

Then I went to the opera, sat in a box diagonally across from the imperial box, and all evening studied the motions of the German Kaiser. He sat there stiffly, sometimes bent affably to our Emperor, laughed heartily a number of times, and in general was not unconcerned about the impression he was making on the audience. At one time he explained something to our Emperor and underlined it with firm, vigorous, small gestures with his right hand, while his left hand rested permanently on the hilt of his sword.

I came home at eleven o’clock. Hechler had been sitting in the hall for an hour waiting for me. He wants to leave for Karlsruhe as seven in the morning.

He sat with me until half-past twelve making gentle conversation. His refrain: fulfill prophecy!

He firmly believes in it.”

“April 15

Hechler left as scheduled this morning. I went to his place to inquire about it; that is how improbable it still seemed to me, despite everything.

Hechler had managed the impossible. While the Kaiser visited the Grand Duke, Hechler had approached the Kaiser about Herzl and Zionism. .

April 16

Hechler wires to me from Karlsruhe:

Everyone enthusiastic. Must stay through Sunday. Please hold yourself in readiness. Hechler.”

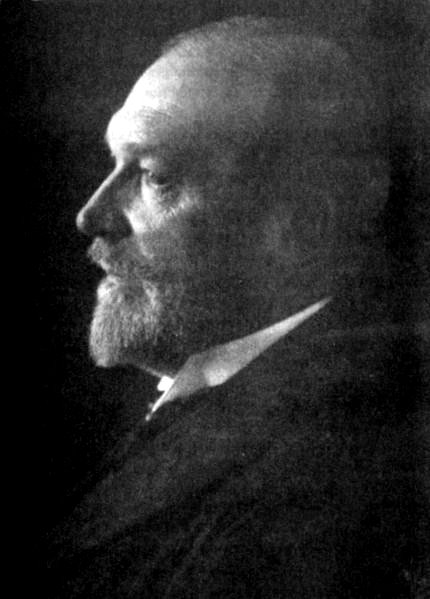

Grand Duke Frederick I of Baden, Uncle to Kaiser Wilhelm II

“Vienna, April 16, 1896

For today my project has come a step closer to realization, one that may be historically memorable. Reverend Hechler, who has gone to Karlsruhe to win the Grand Duke and through him the Kaiser for the idea, has wired me to be read to come to Karlsruhe.”

April 18

No word from Hechler. I now explain it to myself this way: with this telegram Hechler wanted to let me down easy about the failure of his mission. But since, in any case, he will have brought my pamphlet to the attention of the Grand Duke and perhaps even to that of the Kaiser, his traveling expenses are worth it to me. I shall give them to him without making a face, because that way I shall make all the more certain of his good services in the future.”

“April 18

Hechler wires from Karlsruhe:

Second conversation with H.M. and H.R.H. yesterday excellent. Must wait some more Hechler.

(His Majesty- the Kaiser, His Royal Highness – the Duke of Baden)

April 21

Heard nothing more from Hechler. Meanwhile the Kaiser has left Karlsruhe and gone to Coburg.”

“April 21

Hechler telegraphs from Karlsruhe:

Third conversation yesterday. Fourth today, four o’clock. Hard work to make my wish prevail. Nevertheless, all goes well. Hechler”

“April 21

I had intended to go to Pest tomorrow morning. Late this evening I received Hechler’s call to come to Karlsruhe.

A curious day. Hirsch dies, and I make contact with princes.

Now begins a new book of the Jewish cause. After my return I shall add Hechler’s last telegrams to this full notebook.”

“April 22

Before my departure I received another telegram from Hechler:

Cannot possibly remain here till Saturday. Conference with H.R.H. set for Thursday for both of us. Must I really return with mission half accomplished? … I must leave tomorrow if you cannot come by Thursday noon. Hechler.

He had interpreted my yesterday’s message that I was leaving for Pest as a reply to his second telegram of yesterday, which it was not. It is a good thing that he thought it necessary to urge me again. But today, beaming with joy, he will report to the Grand Duke that I am coming after all.

April 23

I arrived here at eleven last night. Hechler met me at the station and took me to the Hotel Germania, which had been “recommended by the Grand Duke.”

We sat in the dining-room for an hour. I drank Bavarian beer, Hechler milk.

He told me what had happened. The Grand Duke had received him immediately upon his arrival, but first wanted to wait for his privy-councilor’s report on my Jewish State.

Hechler showed the Grand Duke the “prophetic tables” which seemed to make an impression.

When the Kaiser arrived, the Grand Duke immediately informed him of the matter. Hechler was invited to the reception and to the surprise of the court-assembly the Kaiser addressed him with the jocular words: “Hechler, I hear you wanted to become a minister of the Jewish State.”

Contrary to etiquette, Hechler replied in English, whereupon the Kaiser continued in English: “Isn’t Rothschild behind this?”

Naturally, Hechler answered in the negative. And with that the “conversation” seems to have been at an end.

So far, then, the results have been rather meager.

On the other hand, Hechler had better luck with the Grand Duke. There he was received a number of times. The Grand Duke spoke of the late Prince Ludwig, whose tutor Hechler had been, and wept freely. Hechler comforted him and read him a psalm I which Zion in mentioned.

Then the Grand Duke was open to further conversation. His main misgiving was that is action might be misinterpreted if he went along with my plan. People would assume that he wanted to drive the Jews out of the country. Also, my status as a journalist gave him pause. Hechler guaranteed that nothing would get into the papers.

At that point that Grand Duke asked what he could actually do for the cause.

Hechler said: “It was Your Royal Highness who, first among the German princes at Versailles, proclaimed King Wilhelm emperor. What if you were to participate in the second great founding of a state in this century, too! For the Jews will become a Grande nation.

This made an impression on the Grand Duke, and he consented to Hechler’s calling me here, in order that I might expound the matter to him.

I am to come to a private audience at four o’clock this afternoon.

I accompanied Hechler to his quarters through the clean deserted streets of this nice capital. Now and then, night owls, coming from a tavern, raised a loud and cheerful shout.

A pleasant provincialism revealed itself to my eyes in these night scenes and in Hechler’s stories. The sentinel in front of the castle gate listened complacently while Hechler told me where the apartments of the Grand Duke and of the Grand Duchess were located and where he himself had once lived. Nostalgically he pointed to the elegant windows. I accompanied him to his door. He is staying in one of the outlying court buildings. “

“Walked and rode about with Hechler. We viewed the mausoleum of Prince Ludwig, which is just being completed. With a solemn beauty this red sandstone chapel stands in the charming hunting forest next to the Wolfsgraben, where young Ludwig to play.’

Astonishingly, Herzl was remarkably ill informed about the very Aristocrats he was attempting to gain access to. Hechler was his tutor in people, events and protocol.

‘I had Hechler give me details about the grand-ducal family, so as to know with whom I would be talking.

I also took a good look at the photographs of the Grand Duke which are displayed in the shop windows. Looks like a well-meaning, commonplace person.

Hechler told me further that the Grand Duke had seemed concerned lest the departure of the Jews might also involve an enormous exodus of money.

I shall accordingly reassure him on this point.”

“April 23

Lunched with Hechler; he had brought his decorations along and was more excited than I was. I did not change my clothes until after lunch, half an hour before the audience. Hechler asked me if I did not want to wear tails. I said no, for too formal an attire on such an occasion can also be tactless. The Grand Duke wishes to speak with me, as it were, incognito. So I wore my trusty Prince Albert. Externals increase the importance the higher one climbs, for everything become symbolic………….

In good spirits I said to Hechler: “Remember this fine day, the lovely spring skies over Karlsruhe! Perhaps a year from today we shall be in Jerusalem.” Hechler said he planned to ask the Grand Duke to accompany the Kaiser when the latter went to Jerusalem next year for the consecration of the church. I should also be present then, and he, Hechler, would like to go along as a technical advisor to the Grand Duke.

I said: “when I go to Jerusalem, I will take you with me.

…………..It was the first time I had driven up before a princely castle. I tried not to let myself be overawed by the soldiers on guard. The door-keeper treated Hechler like an old friend. We were led into the first waiting-room. It was the Adjutants’ Hall. And this did take my breath away. For here the regimental flags stand in magnificent rank and file. Encased in leather, they rest solemn and silent; they are the flags of 1870-1871.

…………..Fortunately, Hechler chattered without a break, too. He told me about the first time he was in this hall when as a young fellow he brought a petition to retain an Inspector of Secondary Schools who was to be dismissed. At that time an adjutant had come up to him and said: “Don’t be afraid! The Grand Duke is only a man like ourselves.”

I thought to myself, smiling inwardly, “That’s good to know, anyway.”

(Herzl was clearly very nervous about meeting the Grand Duke.)

…………Hechler continued to bolster my spirits by his prattle. If he did this intentionally, it was very discreet.

He had, in general, prepared me in a most tactful manner. For instance, he had remarked on our way to the castle that I must un-gloved my right hand, in case the Duke offered me his hand to shake.’

Herzl was very ill informed about international politics and inter-religious rivalry. He added in his diary how Hechler’s insights were fundamentally needed.

‘At lunch I had told him that the Vienna Nuncio, Agliardi, had sent me word (through Dr. Munz) that he wanted to have a talk with me. I told him this so that he might induce the British Ambassador, Monson, to speak with me. Hechler immediately warned me against Agliardi and Rome. He bade me be careful. Meanwhile I thought to myself: just let them be jealous of one another, Englishmen and Russians, Protestants and Catholics. Let them contend over me- that way our cause will be furthered.

While we were sitting in the red salon, Hechler told me about the deceased Grand Duke whose portrait hung on the wall: he was reputed to be of dubious parentage. ……….Listened to Hechler’s story absent-mindedly. I don’t even know if I am reproducing it correctly now.

It only pleased me to hear of these egotistic wrangling among the great, because it made me feel a bit superior in the purity of my own movement and gave me more self-assurance.

Suddenly the door from the study opened, and there entered an old general who looked robust but not obese – the Grand Duke. We jumped up from our arm-chairs. I made two bows. The Grand Duke shook hands with Hechler – but did not avail himself of my fittingly bared right hand.

………….I sat for two and half hours in a strained position, which may also have affected my manner of delivery.

………..So I unfolded the entire subject. Unfortunately I had to concentrate so much while I was speaking that I was not able to observe well. Hechler said afterwards that the conversations should have been taken down stenographical. He thought I had spoken quite well and found some felicitous expressions.

All I know is that the Grand Duke kept looking straight into my eyes with his beautiful blue eyes and calm, fine face, that he listened to me with great benevolence; and when he himself spoke, he did so with ineffable modesty. After exerting my entire brain power for two hours and a half, I was so exhausted that I can no longer remember the exact course of the conversation.

In any case, the Grand Duke took my proposed formation of a state quite seriously from the beginning.

His chief misgiving was that if he supported the cause, people would misinterpret this as anti-Semitism on his part.

I explained to him that only those Jews shall go who want to.

Since the Jews of Baden are happy under his liberal reign, they will not emigrate, and right so. In the course of his conversation I reverted several times more, and from different angles, to his friendliness toward the Jews and used it in various ways as an argument. If he supported our cause, I said, it would no longer be possible to regard it as something hostile to the Jews. Moreover, it was our duty, as leaders of the Jews, to make clear to the people that establishment of the Jewish State would constitute an act of goodwill and not persecution.

Further I said: “If Your Royal Highness” benevolent attitude toward the Jews became know, your duchy would get such an influx of Jews that it would be highly calamitous.”

He smiled.

Grand Duke spoke of Jews in his duchy and administration - very tolerant view.

……….I then presented the entire plan, which he had actually known only in Hechler’s version – that is, in its “prophetic” aspects which, of course, I don’t have much to do with.

Continued entry – April 25

…….To offset this; my movement wants to help on two fronts: through draining off the surplus Jewish proletariat, and through keeping international capital under control.

The German Jews cannot but welcome the movement. It will divert the influx of Jews from Eastern Europe away from them.

The Grand Duke repeatedly punctuated my observations with a murmured “I wish it were so.”

He then half turned to Hechler;

“I suppose that cooperation between England and Germany is not very likely. Relations between the two are, unfortunately, badly disturbed at present. Would England go along?

I said: “Our English Jews will have to see to that.”

The Grand Duke said, somewhat ill-humoredly: “If they can manage that…”

Both Germany and England were being flooded with Russian Jews; neither wanted them – no one wanted them.

“………..Hechler now came to my aide: “Would not Your Royal Highness permit Dr. Herzl to tell a few trustworthy men in England that the Grand Duke of Baden takes an interest in the matter?”

The Grand Duke assented to this, with the repeated stipulation that the matter might be discussed only outside the borders of his country. Then he asked me whether I had taken any steps yet with the Sultan.

Thinking of Nevlinski, I said that someone had already offered to speak with the Sultan.”

Hechler thought faster than Herzl did.

“Hechler said: “Could Russia have designs on Palestine?”

The Grand Duke said: “I don’t think so. For a long time to come, Russia will have her hands full in the Far East.

I asked: “Does Your Royal Highness consider it possible that I shall be received by the Czar?”

He said: “According to the latest reports, the Czar is accessible to on one.”

Hechler drew the conversation back to the true meaning for the Grand Duke.

“When towards the end, Hechler joined in and discoursed on the speedy fulfillment of the prophecy, the Grand Duke listened in silent and magnificent faith, with a peculiar look of peace in his fine steady eyes.

Finally, he repeated something he had said several times before: ‘I would like to see it come about. I believe it will be a blessing for many human beings….”

Herzl clearly misunderstood the Grand Duke’s motivation. He misunderstood because of his own lack of a faith centered base. Herzl continues in his diary.

“Now that I reconsider it all, it seems to me that I have won him over.

After two hours and a half, which were exhausting for him as well, for he often held his head when I was discussing some difficult point – after two and half hours he terminated the audience. This time he shook my hand and even held it for quite some time, while he spoke kind words of farewell: he hoped that I would reach my goal, etc.

Together with Hechler I went past the lackeys and guards who wondered at the length of the audience.

I was slightly intoxicated with the success of our conference. I could only say to Hechler, “He is a wonderful person!”

Hechler left with Herzl from the audience returning without Herzl to the Duke to be sure of things. Herzl is finding Hechler’s advice and counsel extremely important.

“April 26

When I boarded the Orient Express at Munich yesterday at noon, Hechler was on it. From Basel he had gone to Karlsruhe again and there boarded the Orient Express. “I will pay the different in fares out of my own pocket,” he said.

Naturally I wouldn’t hear of it. The whole trip shall be at my expense. In my present circumstances this is a bit of a sacrifice, to be sure.

We had a comfortable trip. In the compartment he unfolded his maps of Palestine and instructed me for hours on end. The northern frontier ought to be the mountains facing Cappadocia; the southern, the Suez Canal. The slogan to be circulated: the Palestine of David and Solomon!

Then he left me to myself, and I drafted my letter to the Grand Duke. Later Hechler found fault with some things. His criticisms are excellent, although it is then that his anti-Semitism occasionally comes through. Self-confidence on the part of a Jew seems insolence to him…..

This man Hechler is, at all events, a peculiar and complex person. There is much pedantry, exaggerated humility, pious eye-rolling about him- but he also gives me excellent advice full of unmistakably genuine good will. He is at once clever and mystical, cunning and naïve. In his dealings with me so far, he has supported me almost miraculously.

His counsel and his precepts have been excellent to date, and unless it turns out later, somehow or other, that he is a double dealer, I would want the Jews to show him a full measure of gratitude.”

In the ensuing weeks, the prairie fire of Zionism spreads through the Jewish world. Herzl is caught in a whirlwind of movement pulling in multiple directions. From one source comes support and from another vilification. Unbeknownst to Herzl, the Grand Duke approaches the Kaiser again about Herzl and Zionism. Herzl is drawn by his other Christian guide, Nevlinksy, to the master of the lands that he wishes to obtain – the Sultan in Constantinople.

The Ottoman Empire is in severe decline. Decay, corruption, neglect and fatigue number the days of its survival. The Ottoman Empire is named the “Sick man of Europe” for a reason. The Western powers are strategizing its dismemberment and vying for the pieces. Utilizing Nevlinski’s contacts, Herzl travels to Constantinople with hopes of an interview with the Sultan. He needs public affirmation of his meetings. There, he discusses his proposals with the Grand Vizier of the Sultan but fails to achieve a meeting with the Sultan. His need for public affirmation has failed. He has piqued the interest of the Turks in the financial aspects of the plan but has achieved nothing else. Herzl is presented as a newspaper representative of the Neue Freie Presse and not the representative of the Zionist movement. There is no Zionist movement. There are only separate groups advancing individual interests.

As Herzl traveled to Constantinople, Jews in small towns came to the rail lines just to watch his train speed by carrying their “Messiah.” Herzl is confused, flattered and distressed.

June 17, 1896

“A gripping scene awaited me in Sofia. Lining the platform, where our train drew up, stood a great throng – who had come on my account. I had completely forgotten that I had been responsible for all this.

Men and women, children were massed together, Sephardim and Ashkenazim, mere boys and white-bearded patriarchs. At their head stood Dr. Reuben Bierer. A lad presented me with a wreath of roses and carnations. Bierer delivered a speech in German. Then Caleb read out an address in French, and finally despite my resistance, kissed my hand. In his and subsequent speeches I was hailed as Leader, as the Heart of Israel, etc. in extravagant terms. I stood there, I believe, altogether dumfounded: and the passengers of the Orient Express stared at the unusual spectacle with astonishment.”

Herzl had been curiously treated if he was nothing more than a press representative with quasi diplomatic respect by the “Sublime Porte”, the Ottomans. He was leaving with nothing. Herzl knew he needed something to show for his effort, something tangible.

“June 29, 1896, after a day of sightseeing and feting by the Sultan’s adjutant, Herzl returned to their hotel.

“When I got back to the Hotel Royal from the sweltering but beautiful trip, Nevlinski, clad only in underwear and writing letters, said to me: “He sends you that!” and handed me a little case containing the commander’s cross of the Medjidie Order.”

Nevlinksi arranged that a medal be given Herzl recognizing his visit. The medal is not even presented to Herzl. The unceremonious receipt is kept from the public. Herzl, the author of the Jewish State, the hope of millions of Jews, has been to Constantinople. He has spoken to the Grand Vizier. It is all that the public knows. Herzl, the Jew, has been presented with a special medal by the Sultan. The public relations triumph, a medal, trumped the material failure of Herzl’s visit. Herzl’s public acclaim along the rail lines back was even greater than on the ride to Constantinople. Inside the train, amongst the Herzl entourage, was quiet gloom.

The Sultan ordered that the borders to Palestine be tightened further to guard against Jews getting in.

Herzl returned to London to report on his progress to the Maccabeans. As would be the case in many of the key developments that Herzl was and would be involved with, he would not fully revealing what happened. Herzl was shaping events. Herzl was creating a movement through the force of his will and the faith and the desperation of millions of Jews.

The news of Herzl’s trip to the court of the Sultan traveled about the world. In some places it traveled with the speed of electrons. In others, it traveled much slower and sometimes months behind.

Herzl’s efforts were generally cynically reviewed by the Western Press.

July 4, 1896, the British tabloid, The Hackney Express, commented on Herzl’s adventure.

“Periodically some enthusiastic Semite puts forward a plan for a Jewish State in Palestine, and if the Jews like to go there and can induce the Sultan to guarantee to them the autonomy for which they profess to be anxious, by all means, let the bargain be struck. But what would the Jews do there? They are a practical race; their main business is to act as intermediaries in the commercial and monetary transactions of the world. They are neither manufacturers nor agriculturists. Even if they were, a worse country for either of these industries cannot well be conceived. The proposal is about as reasonable as it would be to send a colony of sheep-shearers to a land where there are no sheep to shear.”

The London Daily Mail, the largest and most widely read newspaper in Great Britain, with major influence on the world press, carried Zangwill’s scathing analysis of Herzl and his accomplishments.

July 10, 1896

“The Promised Land

Mr. Zangwill on the projected Jewish State

I have noticed a good deal of comment, especially in the continental press, on a new scheme for the formation of a Jewish state; and in the English press, indeed, I seem to be mixed up with it myself. But my connection with the project is merely superficial. Dr. Theodor Herzl, its author, came to me from Vienna some seven months ago, with an introduction from Max Nordau. He was an enthusiast in a hurry, for he wanted to be back in Vienna in three days time, and yet expected me to enable him to address a meeting of leading London Jews. To anyone who knows the difficulties of getting men together in London, where men will not eat the best dinners without weeks of forewarning, this expectation seemed enough of itself to stamp the man and his projects as unpractical. But when I say that this strange visitor, dropped from the skies, not only addressed his meeting, but in the same three days travelled to Cardiff to interview Colonel Goldsmid, it will be seen that the age of miracles is not yet over. Furthermore, Dr. Herzl greatly impressed his hearers, not so much with his project as with his personality. Tall, black bearded, handsome, a fine figure of a man, a brilliant orator, infinitely dexterous in debate, and able to address his audience (like Cosmopolis) in three languages, he proved an extraordinary combination of idealist and man of affairs. And when, some months later, his pamphlet on, “The Jewish State” was published, it was found to exhibit the same qualities as his oratory, with however, the practical side at its maximum and the idealistic its minimum. So afraid was he of being called a dreamer that he concentrated himself almost exclusively on the financial, political, and politico-economical aspects of the question. If anything, there is too little appeal to the emotional, not to say the religious side of such a movement. What his exact proposal is may be best seen from the English translation of his pamphlet made by Miss d’Avigdor, and published by David Nutt, though its author is characteristically ready to accept any amendments or even transformations. Suffice it to say here that the scheme has nothing consciously to do with “the prophecies,” though it is open to anyone to believe that the instruments of Providence may be unconscious. Mr. Holman Hunt is far more alive to the poetical side of the Jewish Restoration than Dr. Herzl. Readers who take their ideas of latter day Jewish prophets from Mordecai in “Daniel Deronda” would find the Hungarian doctor of law a very modern Mordecai indeed.

For it is no dream of a universal spiritual hegemony that has inspired the latest preacher of an old idea.

Dr. Herzl is a journalist who, born in Budapest, became the representative of the “Neue Freie Presse” in Paris, which position he finally surrendered to Max Nordau when he went to join the staff at Vienna. In the Austrian capital he made a reputation by comedies, successfully produced at the leading theatre the Bourg Theatre – and by a “Book of Nonsense” It is this humorous side of him supplemented by that experience of men and affairs which journalism gives, which is doubtless accountable for the sobriety of his propositions.

In his scheme the Messiah comes almost in the shape of a joint stock company and the return to Palestine would be not only a political move but one that would pay in the long run. The doctor has, I think been irritated in his idea by the anti-Semitism now so predominant in Vienna, the intensity of which the Jews of happier England can hardly conceive. And it is therefore for these English Jews, thinks Dr. Herzl, to take the lead in the movement. Moreover, says he, this is the age of nationalities. The eighteenth century idea of cosmopolitanism has proved unworkable, and it is recognized that the world gains by diversity of peoples and ideas. So divorced is the doctor from conventional Jewish ideas that Palestine did not at first seem to him the necessary centre of a Jewish state. Any country obtainable, even Argentina, where the late Baron Hirsch’s colonies are planted, seemed to him satisfactory enough.

The point was, or is, to get a district where a Jewish autonomous state might be established to which all the streams of the persecuted would flow. There would be no necessity for the trotting out of the old joke about Rothschild wanting to be Ambassador to Paris. Jewish who did not want to go could remain where they were. It would only be a political haven for refuge for the poor and the suffering and the process of building it up would be very gradual, success attracting more and more settlers from oppressed districts. As it is, Jewish refugees wander here, there and everywhere, nearly always inhospitably received. Why should they not tend to a centre of their own, where they would have an opportunity of earning a livelihood by agriculture or foreign trade,… (ungalled ?)… save by their own self imposed restrictions? Such an idea is plausible enough, though it is beset with difficulties, some of which Dr. Herzl has not recognized, and with other of which he has endeavored, more or less successfully, to grapple. But the response to his plan, the letters and addresses sent him by Jews of many countries endeavored, more or less successfully, to grapple have shown him that he was wrong to rely solely for a motor force in the suggested movement on the external compulsion of persecution. He found that there was good deal of inner enthusiasm to be counted upon and indeed the Jewish national idea existed before Dr. Herzl was born, and has supporters in every country.

Branches of the “Choveve Zion” Inhabitants of Zion – Association may be found everywhere throughout Europe and America. In London the society boast a quarterly magazine, “Palestine,” ably edited by Dr. S.A. Hirsch, in which may be read accounts of all that is being done for the planting of Jews in Palestine, and of the great success of at least one of Baron Edmond de Rothschild’s colonies. And this ancient sentiment for Palestine has persuaded the new enthusiast to make it the centre of his own scheme and indirectly, has turned the dreamer into a man of action. For his first intention was merely to put forth his scheme as a thinker, but as he himself says, unlike Shakespeare’s Christopher Sly, who suddenly found himself in a world of fantasy, he suddenly found himself in a world of action. He has gone so far as to interview the Sultan or at least the Grand Vizier at Constantinople, and to obtain what he hints are important concessions, though his opponents aver that he has only been taken in by the wily Turk, who after receiving him with the greatest honors cabled to Palestine to enforce more strictly the law against the admission of Russian Jews.

It will be seen that the scheme is largely a counsel of despair. Dr. Herzl does not believe that anti-Semitism will ever die so long as the Jews are settled among other people, for says he, it is not their bad qualities but their good qualities that excite hostility. It is their success, their energy, their superiority to their environment. But with this, I cannot quite agree. When I was in Vienna the other day, I found its Jews not altogether blameless. Too many of them are on the Stock Exchange; too many of them flaunt their wealth obtained by this jugglery. Such Jews are Jews only in name even when they keep to Jewish religious customs which most of them do not. Israel has this particularity among the nations -that it is linked by a spiritual idea, and therefore an appeal merely to common blood has less magnetism than with other peoples. Where Jews have become materialists, they must be left to their fate. If they arouse envy and hatred in countries where Jews play honorable parts in the spiritual and intellectual life of the nation, I do not believe that a revival of mediaeval prejudice is inevitable. Dr. Herzl’s scheme was conceived in the midst of an anti-Semitic agitation, and bears the marks of disproportion and want of balance, which are the natural outcome of thinking in a panic. At a dinner given to him the other day by the Maccabeans, it was resolved to form a small committee to investigate this idea. But his will have no connection with the Maccabeans themselves. So far as England is concerned, nothing is likely to be done, unless some great outbreak of persecution abroad stirred up English Jews; but, on the whole, Dr. Herzl has undoubtedly given a fillip to the Jewish National Idea.

I.”

Herzl’s efforts continued making news around the world. The reception and perception of his efforts were more mixed.

San Antonio, The Texas Daily Light wrote, August 8, 1896

“The New Jewish State

Vienna, Aug. 8 – The informal negotiations set on foot last year for the establishment of a Jewish autonomous state in Syria made considerable progress, and a meeting was held on the 6th ult. under the auspices of the of the Maccabean society, to consider the report of Dr. Theodor Herzl, of Vienna, the author of the new scheme. Although no organization has yet been formed….”

Salem, Massachusetts, The Daily News, November 11, 1896.

“A Jewish State in Palestine

We understand says the London Daily Graphic that practical steps are being taken for the re-establishment of a Jewish State in Palestine. A scheme which was drawn up last year by Dr. Herzl of Vienna and subsequently published as a pamphlet in German and English has found considerable favor among the Jews in Vienna, Paris and London, and Dr. Herzl has lately been actively employed in enlisting political support for it. Some of the leading statesmen of Europe have been consulted and Dr. Herzl, who is at present in Constantinople, has had a long interview with the Grand Vizier, with whom he has discussed the project. After visiting Vienna and Paris again, Dr. Herzl will come to London to report progress to a committee of the Maccabean Society.”

By August, 1896, Herzl knew he needed formal legitimization. Herzl needed affirmation by a unified Zionist movement, an international Jewish organization that would recognize his leadership and his position as the Jewish National negotiator. The Zionist movement was fragmented, decentralized and without coordination or control. Herzl knew world opinion could not be shaped and supported by loose, narrow focused efforts or tiny philanthropic societies such as the Maccabean Society. Herzl understood marketing and public relations very well. August, 1896, Herzl began to organize, to direct, to assemble, what would become the first World Zionist Congress. It was scheduled to meet August, 1897. The Congress would codify, in stone, Political Zionism and Herzl as its leader.

The months between August 1896 and August 1897 was a year of super human effort for Herzl and his tiny staff working on the Der Welt. Herzl continued traveling, continue speaking, continued writing with maniacal fury to create the Zionist Congress. Without the Congress, he had no major World Power recognition of him or Zionism. He had nothing to show for his efforts except the Sultan’s medal, a number of minor Jewish honors and a lot of Jewish anger.

Reverend William Hechler did not sit quietly since he first met Theodor Herzl in March. He did as he promised Herzl. He traveled to Berlin to try and reach the Kaiser. He was unsuccessful in March. He was spectacularly successful in April. He did speak, briefly, of Herzl and Zionism to the Kaiser. But, much more importantly, he arranged a major interview with the Grand Duke of Baden for Herzl. He had prepared the road for Herzl and planted the seeds of Zionism in the heart of the Duke. Hechler fertilized the way with deep religious Restorationist theology. Herzl did meet the Grand Duke. He did gain a powerful, influential, well connected ally.

Hechler understood that to get the Kaiser to support Herzl and Zionism it would be a process, at times indirect, but a process of building and gradual door openings. Hechler understood the young Kaiser’s personal ambitions for his reign were not religious but politically ambitious. Kaiser Wilhelm saw himself in an imperious role as a builder of German influence and power. Religion was a factor but not the principle key to getting the Kaiser to act. Hechler did not stop. He aggressively and energetically began contacting the Christian religious community. He spoke of Herzl and Zionism and prophecy.

Immediately after Herzl had met with Hechler and the Grand Duke in April, Hechler had secured permission for the meeting to be told abroad. Hechler, excitedly, told Herzl he would compose a letter of announcement to the members of his English church. Herzl, afraid to permit Hechler to act through the faith world that it might impact on the political world, forbade Hechler to proceed. Herzl would later regret that decision.

Hechler wrote and spoke and shared the reality of Herzl to anyone who would listen. He brought his church superior, Bishop Wilkinson, to meet Herzl. Herzl politely complied but did not grasp the significance of the meeting and the potential power of the pulpit to tell the story of Zionism. Wilkinson was a short, public relations, interruption to Herzl. Hechler understood Wilkerson as a powerful public relations messenger. Herzl responded abruptly to a misconstrued anti-Semitic slight from Wilkinson.

From Herzl’s diary, June 9:

“In the afternoon at Hechler’ s home I met the English Bishop Wilkinson, a clever, slim old man with white whiskers and dark, intelligent eyes. The Bishop had already read my pamphlet and thought it was “rather a business.” I said categorically: “I don’t make business. I am a literary man.” Whereupon the Bishop declared that he had not meant this as an insult. On the contrary, he regarded the matter as a practical one. Even though it might start as a business, it might become something great. After all, England’s Indian empire had also come into being unconsciously. In the end he blessed me and invoked God’s blessing on the project.”

Hechler continued to work with the fire of faith in his chest for Herzl and Zionism. Herzl did not comprehend Hechler, even guardedly still distrusting him. Herzl’s diary lays bare his feelings.

“July 30, Aussee

Hechler telegraphs from Tegernsee:

Am at Tegernsee, Villa Fischer, made speeches in the castle and at homes of important people. Everybody enthusiastic.

“Can you come immediately to lend dignity? I want to leave here about Saturday – if possible.

Hechler.

Aug. 1, Aussee

Hechler telegraphs from Tegernsee: “Today fifth and last presentation. Leaving today or tomorrow morning.

Hechler.”

This means then, that the important people mentioned in his first wire are not issuing a direct invitation to me.

Or did he merely want me to come on a chance? In any case, I did well not to start off right away.”

Through the fall and winter of 1896-1897, Hechler continually tried one door after another to gain a contact that can give access to the Kaiser. He wrote to the Kaiser, on British embassy stationary, to give it an official feel. Using his connection to a friend, Prince Gunther, Hechler attempted to have the letter delivered. The prince declined to deliver it. Herzl sent Hechler his Russian translation of Der Judenstaadt hoping that Prince Gunther would deliver it to the Tsar. Hechler wrote to Lord Salisbury in England on behalf of Herzl.

Mid December, Hechler brought a newspaper clipping to Herzl. It would be propitious. It could be a major opportunity for Herzl and Zionism if they could get to the Kaiser. The Kaiser was planning to go to Palestine in October of 1897.

Philipp-Fuerst-von-Eulenburg (1847-1921)

March 14, 1897, Herzl writes:

“A letter-card from Hechler. He writes that upon his return from Merino he found waiting for him an invitation from the local German ambassador Eulenburg, who is greatly interested in our cause. Has Hechler dreamed this? It could be true. As a literary dilettante Count Eulenburg in any case know my name. He is a confidant of the German Kaiser. If I win him over, he can bring me to the Kaiser at last.”

Herzl again missed the connection. Eulenburg’s wife had been, at one time, a pupil of Hechler’s. Herzl automatically assumed it was about him and him alone that the contact may have been made. Eulenburg was a particularly important contact. He was one of the Kaiser’s closest personal friends and advisors. It would be almost a year and a half until Herzl finally met Eulenburg.

The first Zionist Congress was scheduled for late August. Herzl was expending great amounts of time, energy and his wife’s personal fortune on the Zionist project. The central need to create a Bank that would be able to amass the monies of the Jewish people to buy Palestine was still not realized. The great Jewish families, with the great fortunes, had turned Herzl away. Herzl’s strongest Western line of support, British establishment Jewry, turned away from him as the British Rothschild family rejected Herzl and his Zionism. Colonel Goldsmid, and the majority of the members of the Maccabean Society, refused to participate with Herzl in deference to the Rothschilds. Only the youth and the newly immigrated to Britain joined with him. British Jewry largely separated from Herzl. Britain’s, as had Vienna’s and France’s, Jewish religious establishment rejected Herzl. Herzl struggled on, even harder, to bring the disparate pieces of Jewry together in a single Congress. The Congress was planned to be held in Munich. Munich’s rabbinic community and Jewish community protested violently to the local government. In the last number of weeks before the Congress was to begin, Herzl was forced to move the Congress to a “safer” location – Basel, Switzerland.

Just days before the Congress, Herzl encounters Hechler in Innsbruck. Hechler was continuing to Basel for the Congress.

“Aug. 24

On, the train, en route to Zurich.

This morning, when I was coming down the stairs in the Tiroler Hof, who should step up to me? Hechler! He had been there since the night before, and was delivering a lecture in the salon about me and my movement while I was taking a solitary evening stroll through the streets of Innsbruck, thinking of anything but that the upper ten in the Tiroler Hof were at that moment being instructed in Zionism by a clergyman.

Hechler groaned softly but audibly about the discomfort of his third class trip.

I shall wire him 25 guilder from Buchs, with which he can convert his ticket into second class.”

In a shocking revelation Herzl admits to his diary something that he admitted to no one. The Zionist movement, the Zionist Congress, is his personal invention. It is a creation of perception, hope and change. Herzl’s creation lacked substance and true accomplishments to date. Herzl’s Christian Zionists, whom he recognized Hechler as his first Christian Zionist, will be there as non-voting observers, Hechler, Nevlinski and Barron Maxim Manteufell.

‘An odd thing, one of the secret curiosities of the Congress is the fact that most of the threads which I have spun up to now will converge in Basel. Hechler is here, Nevlinski will be, and tutti quanti (all the rest) who have helped in creating the people’s movement under my direction. It will be one of my tasks to keep them from noticing one another too much, for they would probably lose something of their faith in the cause and in me if they saw with what slight means I have built up the present structure. The whole thing is one of those balancing feats which look just as natural after they are accomplished as they seemed improbable before they were undertaken.”

News of the Zionist Congress was world news.

The London Daily Mail, July 30, 1897

“London Good Enough

Jews on the Palestine Scheme

The picturesque proposal of Dr. Theodor Herzl for the floating in London of a limited liability company with a capital of millions to acquire Palestine and thoroughly organize it for the re-settlement of the Jews is attracting great attention, in view of the congress which is to be held at Basle to consider the scheme in August.

The proposal which has several times been referred to in the “Daily Mail”, “the Jewish Chronicle,” and the “Pall Mall Gazette,” among other papers is received with mixed feeling by the London Hebrews. While some like the Rev. Dr. Gaster believe in the probable success of the scheme, others remind one of the remark attributed to a member of the Rothschild family, that “If the Jews ever return to Palestine, I hope they will let me be their ambassador to London.”

The Chief Rabbi Dr. Adler was seen by a representative of the Daily Mail” yesterday. Here are his views: “I fully endorse what has been said on the subject by the Rabbis of Germany, men of most different shades of religious thought. I consider that the holding of this congress is an egregious blunder. While I yield to one in being an ardent lover of Zion, while I lay the greatest possible stress on the importance of establishing colonies in Palestine, while I think it of the utmost moment to generously support and wisely, justly, and intelligently to administer the various institutions in the Holy Land, I believe that Dr. Herzl’s idea of established a Jewish State there is absolutely mischievous.

It is contrary to Jewish principles, the teaching of the prophets and the traditions of Judaism. It is a movement that can be fraught with incalculable harm, which can be entirely perverted and may lead people to think that we Jews are not fired with ardent loyalty for the country in which it is our lot to be placed. And in saying this I believe, I am expressing the opinion of, with a few exceptions, the entire Anglo-Jewish community.

Another gentleman holding a responsible position in metropolitan Jewish circles said: “The question is exciting a tremendous amount of attention among Jews everywhere but especially in England. Sir Samuel Montague said to me recently in expressing an adverse opinion of Dr. Herzl’s plan, “I am an Englishman and all of my aim is to Anglicize the Jews with whom I come in contact. I therefore view the internationalism of Dr. Herzl and his supporters with great disfavor. With regard to the language to be spoken in the Jewish State of Palestine – when it exists – that is a matter to which I myself drew Dr. Herzl’s attention. He advocates a federation of languages.

‘But won’t you all speak Hebrew when you get there?’ questioned our representative.

‘I shan’t for one,’ was the reply, accompanied by a smile.

‘But perhaps you don’t think of going? You know there is a general impressing abroad that the Jews in this country are too well off to care about roughing it in Palestine.’ At this he laughed and shrugged his shoulders significantly; and our interviewer continued, ‘I see Dr. Herzl favors a Democratic Monarchy (whatever that may be). Who is to be the new King Herod in this New Jerusalem? And what do the Jews want with a State of their own? Do they not already govern nearly all European nations?’

Again, the interviewee laughed, this time slyly and with a spice of triumph: ‘What do you think?’ he seemed to say. Then he added more seriously, The fact is, Dr. Herzl is a dreamer of dreams; he writes the feuilletons for the New Free Press of Vienna, and that conduces to the cultivation of imagination.

Had Mr. Gladstone been solicited for an opinion yet? ‘Yes’, he sent it on the usual postcard to the leaders of the Zionist movement. It read: ‘My inclination would be to view with favor any reassembling of Jews in Palestine under Ottoman suzerainty. But I assume there would be absolute religious liberty and equality.’

It is notable that Mr. Gladstone thinks the Sultan would make an excellent suzerain for the chosen people, however evil a genius he may prove to Armenians and Cretans.”

A week before the Zionist Congress, the New York Times reported, August 22, 1897.

“Leaven in German Masses

Jews are split on Zionism

Jews Against Zionism

A violent split has taken place among the Jews all over the world. It is caused by the new course which Zionism recently adopted, and which is to find practical expression at the Zionist Congress to be held at Basle on the 29th, 30th and 31st. inst.

The meaning of Zionism hardly needs explanation. Up till recently Zionism as it is known, had only a religious and philanthropic tendency, and found many adherents also among believing Christians in England. But since the persecution of the Jews began in Russia and Romania some ten years ago and since anti-Semitism in Austria and Germany made the social position of the Jews more intolerable than it was before, the thought of establishing a Jewish state, if possible in old Judea, has gained ground, not only among the Jews of those countries mentioned but also among the Jews in the rest of the world. Many of them thought that a purely philanthropic movement would always be but a palliative, and would never lead to a solution of the Jewish

Question. The many millions spent by Baron Hirsch and Rothschild on colonizing have produced only very slight results. And so arose the idea of political independence. The once philanthropic Jewish party of Zionists adopted a wider program, so that now Zionism actually connotes the revival of the Jewish nationality by the establishment of a Jewish state. In short, Zionism has become a political and social movement. The idea had its origin among the Jews of Eastern Europe where they are more or less persecuted or oppressed, as in Russia and Romania, and even too, in Austria: but curiously enough the movement has been eagerly fostered by many Jews in American and England, where Jewish citizens enjoy full and equal liberty with their Gentile fellow citizens. The consolidation of nationalities is a characteristic feature of our century. Italy, Greece Romania, Serbia, and Bulgaria owe their existence to the principle of nationality, a principle no less powerful and perhaps no less erroneous than was that of the Crusades, but one that urges on the people of this century with an irresistible force. National integration is carried so far in Europe that petty peoples, whose very names have hardly reached your shores, peoples so insignificant that they have neither la literary nor a spiritual past which have possessed a grammar and dictionary of their own languages only for the last ten to twenty years are struggling for their national individuality with greater zeal and passion than those displayed in their pursuit of all other worldly goods, important as the latter may be. Jewish students hold aloof.

Considering this tendency, it is no wonder that the idea of political resurrection has taken possession of that race which produced monotheism, and which during 2,000 years of oppression has given numerous proofs of intellectual vigor and vitality. Only a few years ago no educated Jew in England, Germany or Russian would have dreamed of calling himself anything but an Englishman, a German or a Russian. Today many are heard to say that they are only Jews. It is chiefly young people that have been seized with this unpatriotic tendency which is so hurtful to them. At the universities of Berlin Vienna and other German towns the Jewish students have almost entirely given up the intercourse with the students of other creeds, which was carried on so pleasantly for decades. They have left all the common students societies. In Vienna alone for some years there have been five academic societies for Jews only. With positively fantastic enthusiasm the young men cling to the dreamed of ideal of a Jewish state. No doubt anti-Semitism in Austria and German has done a great deal to drive young Jews to this senseless and dangerous course. But it is not surprising that it has come to that. The Gentile university students are most anti-Semitic. But youth soon exaggerates and over-flown. Formerly the brotherly understanding among the student of different races and religious was complete; creed and race were never thought of in their social intercourse. But now matters have utterly changed. Jewish students are met with blind racial hatred. No distinction is made; they are all socially banished. All noble qualities are denied them. They are declared to be nobodies. An insult from a Jew is no insult. At German universities dueling is still very usual. Jewish students are never challenged, or it is said a Jew is an unworthy individual, incapable of giving satisfaction.

Leaders of the Movement

Political Zionism has been awakened and promoted chiefly by Dr. Herzl’s book, “Der Judenstaadt” (the Jewish State) a clever but rather Utopian book, which was translated into all European languages immediately after its publication. Dr. Herzl and Dr. Max Nordau in Paris are the chief literary exponents of this new movement. Dr. Herzl has told me that the leaders are endeavoring first of all to organize a wholesale migration of Jews from all countries. A “Society of Jews” is to be formed: in London there are already considerable funds at its disposal. A plan has been formed for acquiring part of Palestine from Turkey and settling the immigrants there. Out of its duns the society would pay the Sultan a considerable annual tribute on the strength of which he could raise a loan for the purpose of consolidating the disordered funds of his empire. In return he would protect the Jewish state which would have complete self government. The leaders hope for great things from the congress, at which resolutions are to come which will lead to the execution of the scheme.

Meanwhile, however, a serious countermovement has arisen, especially among the German Jews. Originally it was intended to hold the congress at Munich but the German Jews protested against it. It has now become apparent that only a small number of the Jews in all countries favor these fantastic plans. As long as the projects were only on paper these objectors held their peace. But now that attempts are being made to carry them out, the great majority of thoughtful and serious Jews throughout the world have commenced a decided opposition to the unrealizable and damaging schemes. This majority emphatically denies the existence of a Jewish nationality and condemns the new Zionist postulates. The majority hold that which alone unties the Jews of diverse countries. They are quite different from one another in language, manners, customs, thought and culture. Such heterogeneous elements cold never be welded together into a state. They simply would not understand one another. But apart from that they feel themselves modern citizens of those lands which their ancestors lived for centuries.

A Split over the Congress at Basel

The new theories are only likely to compromise their patriotism toward the countries they live in without helping the Jews of Eastern Europe. For even were it possible to found a state artificially and in a barren country such as Palestine now a land which would require many years of hard labor to restore its former fruitfulness they characterize it as madness, that honest men should subject themselves to the protection of the “Great Assassin” whose conscience is o little troubled by the blood of tens of thousands. Could any state begin by connecting itself with the blackest crimes, the most barbarous and villainous, maladministration prospect? The German Jews have accordingly been the first to declare against Zionism. The rabbis of Berlin, Frankfort, Munich, Dresden and Hamburg have issued a manifesto to their co-religionists to the effect that the establishment of a Jewish State would be contrary to the Messianic prophets and that Judaism lays upon its adherents the obligation to support and foster with all its devotion and with all their might the State they live in. Accordingly the rabbis call upon the Jews to oppose the Zionist ideas as contrary to Judaism but especially to keep away from the Basle Congress. Similar declarations are likely soon to be made by the Jews of other countries. Consequently it is doubtful if the congress which is to be attended by Zionist Jews from all parts of the world will in face of that split be able to proceed to the realization of these Utopian schemes.”

First Zionist Congress – Basel, August, 1897

Herzl’s and the Zionist movement’s dramatic Congress took place in Basel. To emphasize the theatric, all attendees were required to be attired in formal wear with top hats. The Congress took on an air of international statesmanship. It was all still an illusion without international legitimization. They needed to be recognized by a great power of Europe otherwise their efforts were resolutions of empty paper. They had no ability to compel or implement anything amongst themselves and certainly not on the Sultan. The vast inflows of reputed Jewish money to the movement, that even Herzl along with the anti-Semites thought existed, never materialized. Monies to buy Palestine and to pay an annual tribute, bribes to the Sultan and his corrupt administrators, were not there. The Zionist Colonial bank to fund the Ottoman project and Zionist resettlement was finally realized a year later in 1898. The bank was an undercapitalized shell. The Zionists only had a fraction of the monies that they had dreamed they could accumulate.

The Jews are a small and weak people spread across the globe. Herzl understood that all too well. Herzl’s preference for world power recognition of Jewish nationalism and legitimization remained the German Kaiser. He was no closer after the first Congress to his goal or the Kaiser than he was before the Congress.

Repeatedly, frustratingly, Herzl kept on trying every door to the powerful of Europe. He urged Hechler to continue his efforts. Hechler did.

The year between 1897 and the second Zionist Congress in 1898 was a long difficult one for Herzl. Money problems, tensions in his home life, his own health increasingly showing signs of deterioration, the inter-Jewish community fighting, demands that he travel to speak, all took their toll on Herzl. Despite everything, he doggedly stayed the course. 1897- 1898 were Hechler’s years of prophetic prediction. It did not look good for the Zionist movement or for Hechler’s prophetic calculations. Hechler continued spreading the word of Zionism, Herzl, his Messianic vision and keeping close contact with the Grand Duke of Baden.

June 5, 1898, Herzl records in his diaries:

“Hechler is here again and reports that the Grand Duke of Baden reacted favorable when he spoke about me and the Welt. The Grand Duke advised Hechler to win over Eulenburg, the ambassador here. For the cause. The Kaiser, he said, listens to Eulenburg. Hechler should tell Eulenburg in the name of the Grand Duke that in the latter’s opinion something was involved that might prove to be important for German policy in the Orient.

I am writing to the Grand Duke:

Your Royal Highness:

Reverend Hechler tells me that Your Royal Highness is still interested in the Zionist movement and suggested that he call on the Vienna ambassador, Count Eulenburg, for the purpose of arranging my audience with His Majesty the German Kaiser.