Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

“I Will Never Forget You”:

Letters from Jasionowka - 1887

By Heidi M. Szpek

“… You ought to be ashamed of yourself! Whether you have [deliberately] kept silent or whether you are prevented by commitment, dear brother! Therefore, beloved brother, do it now! Make time for yourself so you can write me everything. [Tell me] everything that you yourself have seen until this moment … and by doing this I will never forget you. I will always answer your letter. But at the moment, I will give you no news of myself!!

Your faithful sister, Reina

So concludes a letter from a “faithful” sister to her beloved brother, dated 28 October 1887. After the date, the name of her town is added – Jasionowka. Today Jasionowka is in northeastern Poland; in Reina’s time it belonged to Russia. In this excerpt, Reina chastises her brother for failing to write with news of his travels. But Reina – if that is indeed her name – did not just write one letter to this missing brother, she wrote ten such letters, dated 28th and 29th October; 2nd, 9th, 10th and 11th November, 1887. Most peculiar is that the content of these letters is identical save an occasional spelling variant and a calligraphic hand that crescendos with anger on the 2nd of November. Who was this ‘Reina’? What happened to her “trustworthy” and “beloved” brother? Why would she repeatedly rewrite this same letter? A glimpse into her world of Jasionowka and the circumstances of these letters’ discovery may offer clues to answer these questions.

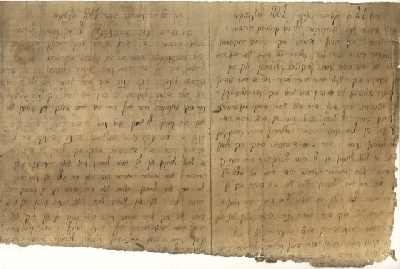

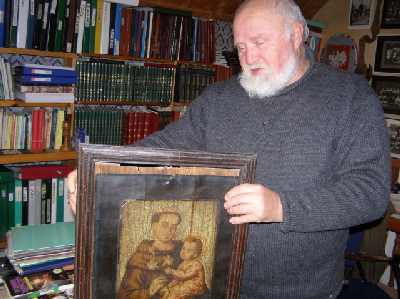

In the late autumn of 2009, in a flea market in Suprasl, Poland, a small town about 15 miles from Jasionowka, a local book and antiquities dealer purchased a large painting of St. Francis and the baby Jesus set with an old wooden frame. On returning home, the dealer examined the back of this painting. On removing the back, a voice from Jasionowka’s lost Jewish world was revealed! Five pages of what appear to be ‘letters’ in cursive Yiddish handwriting had been carefully tucked in the back of this painting.

Figure Discovery of Letters 2009

The town of Jasionowka, some 30 miles north of Bialystok, today belongs to Poland. Jasionowka today and in the past was never a large town; on the eve of the Second World War it was home to less than 2000 inhabitants, two-thirds of whom were Jewish. First mention of this town dates to the mid-16th century in reference to the construction of its church. However, Jews first arrived in Jasionowka in the latter half of the 17th century, conducting business and trade related to beer production, but especially engaged in commerce related to tannery and textiles. By the end of the 18th century Jewish tradesmen were tailors, butchers, liquor distillers, furriers, a shoemaker, a smith, a dyer, a barber, a blacksmith apprentice, a glassblower, an oven builder, and wagon drivers, who moved their products throughout the region, as far afield as eastern Prussia.

Jasionowka’s first wooden synagogue was built in the 17th century, with permission to establish a cemetery shortly thereafter. By the mid-18th century, a second and then a third cemetery were founded to accommodate the growing community. So, too, would eventually be built a brick synagogue, later dismantled to construct a larger wooden synagogue with a ritual bath. By this time, too, this Jewish community would be home to a variety of charitable, as well as intellectual organizations and schools, creating an intellectually rich mithnagdim Jewish community, despite the economic hardship for many. Cheders were founded in which girls eventually would also study. As the spirit of the haskalah reached Jasionowka, Hebrew, Russian and even arithmetic was added to the cheder curriculum. By the onset of World War I, Zionism, too, had its impact on the young people of Jasionowka.

Figure Wooden House on Rynek Jasionowka 2010

Such was Reina’s world as she wrote these letters to her beloved brother in 1887. We might envision Reina nightly, beside candlelight, within one of the small wooden homes in Jasionowka’s Rynek. Night after night she sits down with quill and ink, to recopy the same letter, addressed “zu mayn getrayn bruder! liebster bruder!” (“my trustworthy brother! beloved brother”). Calling him “brother” and herself “sister” is reminiscent of the language of beloveds in the Song of Songs. Are Reina and “her beloved brother” truly siblings, or lovers separated by circumstances. Within her letter, Reina writes:

“The business about which you wrote me, which you have successfully conducted in a strange land – I wish you the love of God, that you should be helped in all your business wherever you employ yourself. Only just wander back to me.” A little later she adds: “I am eager to know much news as you travel through many lands – but to no end, you have abandoned your thoughts of writing any news.”

Such language suggests that Reina and “her faithful” or “beloved brother” are siblings and his travels are more business related than a brother furthering his education in a distant yeshivah as was customary in her time. Perhaps her brother was engaged in one of Jasionowka’s textile businesses that took him travelling throughout what was then Russia and Prussia. The “strange land” to which Reina refers may indeed be the distant regions of the Pale of Settlement.

Yet the painstaking efforts to which Reina subjected herself, writing and rewriting this letter, challenges the assumption of familial relationship. Technically, the letters are more properly diary-like entries on now individual sheets of parchment. The horizontal lines and remnant of the hand-sewn binding, suggest there is more to this story. Perhaps entries at one time existed for the days missing between October 28th and November 10th. One might offer that the repetition of this letter is nothing more than an exercise in penmanship. However, the substance of this letter scarcely suggests this letter is simply such an exercise. Each new page begins with the heading, indicating the date and city of Jasionowka. At times, Reina begins the body of the letter again upon the same page, writing until the lines end but not continuing on to the next page.

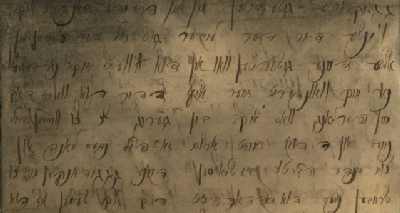

Figure Excerpt of November 2nd 1887 Letter

Again, we might envision Reina nightly, beside candlelight, within one of the small wooden homes on Jasionowka’s Rynek. Night after night she sits down with quill and ink, to recopy the same letter, but something does change – her handwriting. The ‘letters’ of October 28th are in a steady, uniform script. The ink to parchment is of an even tone; individual letters are uniform in the execution. Final ‘nuns’ (N’s) offer a graceful downward stroke, the swirl of the ‘pehs’ (P’s) are consistent, Waws (V’s) and Yodhs (Y’s or vowels) are distinguishable. On the 29th one letter preserves just a few words crossed out with ‘revisions’ written above and even a little ‘doodling’ – as if to test her ink or perhaps a slip of the pen as she tired from her re-writing. Then something happens on November 2nd for Reina’s handwriting changes from steady, flowing script to angry, harsh, thick, and at times elongated, strokes. The words have not changed though but something transpired to raise the passionate ire of “sister” Reina. Her letter mentions that earlier she had safely received a letter from her brother, bringing news of a specific and successful business engagement “in fremda land” (“in a strange land”). Reina is happy for this success but wishes to know more; that she has this wish suggests she has already responded to his earlier letter – but to no avail. Reina chastises her brother to write and notes that “by doing this I will never forget you.” Four times this letter is rewritten in the same steady hand, with an occasional misspelling or spelling variation. Then with November 2nd came a change. The next extant entry is from November 9th. Her handwriting has resumed its careful execution but it is softer; the ink is lighter. With the two entries of November 10th, the calligraphic execution once again resembles the letters of October. Reina’s ire or pain is assuaged.

Perhaps the expression “my faithful brother, my beloved brother” is not the language of sibling devotion but rather the language of love. On October 28th and 29th Reina was still hopeful of news; November 2nd perhaps brought news that he would not return or had spurned her. Yet why continue writing as she did? Perhaps the letters served as an outlet to express her sadness and anger or denial.

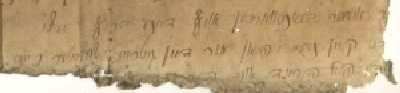

Figure Excerpt from October 28th 1887 – Reina’s name is at the end of line two

What became of Reina is not divulged? In truth, her given name appears on only one letter – the second one dated to October 28th. Archival records from Jasionowka or the surrounding gubernia offer no birth, marriage or death records for a Reina. The Jasionowka cemetery is equally silent to a Reina at this time. We might imagine fate or an arranged married took her to another town to continue her life, though I’d like to think that Reina’s “brother” returned. Yet why keep these letters?

Back to November 1887. When Reina’s “brother” fails to return, she tucks the letters away, perhaps an embarrassment of a love lost or unrequited, behind a painting of her “beloved brother”. Yet another question remains. Why hide these ‘letters’ within a Christian painting? Years later amidst the violence of the Holocaust, an elderly Reina – if still in Jasionowka and surviving the pogrom of 1941 as the Germans took the city from the Russians, would eventually be transported to Treblinka. Reina’s painting remained behind, passing into the hands of local Pole. The photo of her “beloved” was removed to be replaced by a painting of St. Francis and the baby Jesus – both the antithesis of violence and hatred. The letters remained within as padding; their words of love now seemingly silenced and forgotten.

In the end, none of the scenarios offered above may be correct. In the end, what do we gain from invading the private thoughts of Reina. Consider, once again the ‘letter’ that was written and re-written:

The 28th October year 1887 Jasionowka

Much joy and pleasure to my faithful brother! Beloved brother! I have safely received your letter. Much pleasure you have given me. The business about which you wrote me, which you have successfully conducted in a strange land – I wish you the love of God, that you should be helped in all your business wherever you employ yourself. Only just wander back to me. You obviously know that I am eager to know much news as you travel through many lands – but to no end, you have abandoned your thoughts of writing any news. You ought to be ashamed of yourself! Whether you have [deliberately] kept silent or whether you are prevented by commitment, dear brother! Therefore, beloved brother, do it now! Make time for yourself so you can write me everything. [Tell me] everything that you yourself have seen until this moment, and which city you are going to. By doing this I will never forget you. I will always answer your letter. But at the moment, I will give you no news of myself!!

Your faithful sister, Reina

Figure Jasionowka 1916

Figure Jasionowka 2010

Years indeed more than a century have passed since Reina lived and wrote her letters in Jasionowka. The Rynek still stands as it did in Reina’s time; an occasional wooden house still fronts on this city center. However, the view from the southern bridge looking into town no longer includes the rooftops of Jasionowka’s two synagogues. The cemetery still stands outside of town, overgrown though most matzevoth are still in place. Little else remains of Jewish Jasionowka. Reina’s letter ends: “At present, no news from me will be given!” Yet in our contemplation of her words she has given us news – her words reveal there once was a Jewish world in Jasionowka, where most hopefully the greatest concern for a young woman was of love lost or unrequited. And as Reina never forgot her “brother”, we, too, need not forget Reina or Jasionowka.

____________________________________

Heidi M. Szpek, Ph.D. is a Professor of Religious Studies and Philosophy at Central Washington University (Ellensburg, Washington), currently writing a book on the Jewish epitaphs from Bialystok, Poland, with an intense interest in the preservation of Jewish material culture. Her website is www.cwu.edu/~szpekh Dr. Szpek’s most recent journal articles include: “Filial Piety in Jewish Epitaphs” International Journal of the Humanities. Vol. 8/4 (2010): 183-201; “Can Ants Say Kaddish?” The Jewish Magazine (July 2010); “The Miqveh beside the Nurzec River: A Place of Remembrance” The Jewish Magazine (June 2010); “With Whispers, He Spread Torah” The Jewish Magazine (April-May 2010); “Esther of Bialystok” The Jewish Magazine (February 2010); “In the Bloodshed of Their Days” The Jewish Magazine (January 2010); “Wooden Matzevoth” (with Tomasz Wisniewski) The Jewish Magazine (October 2008); “He Walked Upon a Wooden Leg: Epitaphs and Acrostic Poems on Jewish Tombstones” Legacy of the Holocaust Conference 2007 Conference Proceedings. Jagiellionian University Press. Krakow, Poland (May 24-26, 2007), 2008; “‘And in Their Death They Were Not Separated’: Aesthetics of Jewish Tombstones.” The International Journal of the Humanities. Vol. 5 (2007): 165-178; and “Oh Earth, Do Not Cover My Blood!”: Eastern European Jewish Identity and the Material Culture.” The International Journal of the Humanities. Volume 4.4 (2006): 7-18.

Photo copyright: Heidi M. Szpek, Frank J. Idzikowski and Tomasz Wisniewski

~~~~~~~

from the December 2010 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|