|

Four Immortal Chaplains

By Jerry Klinger

Freedom is a work in progress – William

Rabinowitz

Too

few Christians and Jews know the story today. Perhaps even fewer

would know the story of Jewish Chaplain Alexander Goode who died that

night, if it would not be for a single man, a Catholic.

“It was the

evening of Feb. 2, 1943, and the U.S.A.T. Dorchester was crowded to

capacity, carrying 902 service men, merchant seamen and civilian

workers.

Once a luxury coastal liner, the 5,649-ton vessel

had been converted into an Army transport ship. The Dorchester, one

of three ships in the SG-19 convoy, was moving steadily across the

icy waters from Newfoundland toward an American base in Greenland.

SG-19 was escorted by Coast Guard Cutters Tampa, Escanaba and

Comanche.

Hans J. Danielsen,

the ship's captain, was concerned and cautious. Earlier the Tampa had

detected a submarine with its sonar. Danielsen knew he was in

dangerous waters even before he got the alarming information. German

U-boats were constantly prowling these vital sea lanes, and several

ships had already been blasted and sunk.

The Dorchester was

now only 150 miles from its destination, but the captain ordered the

men to sleep in their clothing and keep life jackets on. Many

soldiers sleeping deep in the ship's hold disregarded the order

because of the engine's heat. Others ignored it because the life

jackets were uncomfortable.

On Feb. 3, at 12:55 a.m., a

periscope broke the chilly Atlantic waters. Through the cross hairs,

an officer aboard the German submarine U-223 spotted the

Dorchester.

The U-223 approached the convoy on the surface, and

after identifying and targeting the ship, he gave orders to fire the

torpedoes, a fan of three were fired. The one that hit was

decisive--and deadly--striking the starboard side, amid ship, far

below the water line.

Danielsen, alerted that the Dorchester

was taking water rapidly and sinking, gave the order to abandon ship.

In less than 20 minutes, the Dorchester would slip beneath the

Atlantic's icy waters.

Tragically, the hit

had knocked out power and radio contact with the three escort ships.

The CGC Comanche, however, saw the flash of the explosion. It

responded and then rescued 97 survivors. The CGC Escanaba circled the

Dorchester, rescuing an additional 132 survivors. The third cutter,

CGC Tampa, continued on, escorting the remaining two ships

.

Aboard the Dorchester, panic and chaos had set in. The blast had

killed scores of men, and many more were seriously wounded. Others,

stunned by the explosion were groping in the darkness. Those sleeping

without clothing rushed topside where they were confronted first by a

blast of icy Arctic air and then by the knowledge that death awaited.

Men jumped from the ship into lifeboats, over-crowding them

to the point of capsizing, according to eyewitnesses. Other rafts,

tossed into the Atlantic, drifted away before soldiers could get in

them.

Through the pandemonium, according to those present,

four Army chaplains brought hope in despair and light in darkness.

Those chaplains were Lt. George L. Fox, Methodist; Lt. Alexander D.

Goode, Jewish; Lt. John P. Washington, Roman Catholic; and Lt. Clark

V. Poling, Dutch Reformed.

Quickly and quietly, the four

chaplains spread out among the soldiers. There they tried to calm the

frightened, tend the wounded and guide the disoriented toward safety.

"Witnesses of that terrible night remember hearing the

four men offer prayers for the dying and encouragement for those who

would live," says Wyatt R. Fox, son of Reverend Fox.

One

witness, Private William B. Bednar, found himself floating in

oil-smeared water surrounded by dead bodies and debris. "I could

hear men crying, pleading, praying," Bednar recalls. "I

could also hear the chaplains preaching courage. Their voices were

the only thing that kept me going."

Another sailor,

Petty Officer John J. Mahoney, tried to reenter his cabin but Rabbi

Goode stopped him. Mahoney, concerned about the cold Arctic air,

explained he had forgotten his gloves.

"Never mind,"

Goode responded. "I have two pairs." The rabbi then gave

the petty officer his own gloves. In retrospect, Mahoney realized

that Rabbi Goode was not conveniently carrying two pairs of gloves,

and that the rabbi had decided not to leave the Dorchester.

By this time, most

of the men were topside, and the chaplains opened a storage locker

and began distributing life jackets. It was then that Engineer Grady

Clark witnessed an astonishing sight.

When there were no more

lifejackets in the storage room, the chaplains removed theirs and

gave them to four frightened young men.

"It was the

finest thing I have seen or hope to see this side of heaven,"

said John Ladd, another survivor who saw the chaplains' selfless act.

Ladd's response is

understandable. The altruistic action of the four chaplains

constitutes one of the purest spiritual and ethical acts a person can

make. When giving their life jackets, Rabbi Goode did not call out

for a Jew; Father Washington did not call out for a Catholic; nor did

the Reverends Fox and Poling call out for a Protestant. They simply

gave their life jackets to the next man in line.

As the ship

went down, survivors in nearby rafts could see the four

chaplains--arms linked and braced against the slanting deck. Their

voices could also be heard offering prayers.

Of the 902 men

aboard the U.S.A.T. Dorchester, 672 died, leaving 230 survivors. When

the news reached American shores, the nation was stunned by the

magnitude of the tragedy and heroic conduct of the four chaplains.

"Valor is a

gift," Carl Sandburg once said. "Those having it never know

for sure whether they have it until the test comes."

That

night Reverend Fox, Rabbi Goode, Reverend Poling and Father

Washington passed life's ultimate test. In doing so, they became an

enduring example of extraordinary faith, courage and selflessness.

The Distinguished Service Cross and Purple Heart were awarded

posthumously December 19, 1944, to the next of kin by Lt. Gen. Brehon

B. Somervell, Commanding General of the Army Service Forces, in a

ceremony at the post chapel at Fort Myer, VA.

A one-time only

posthumous Special Medal for Heroism was authorized by Congress and

awarded by the President Eisenhower on January 18, 1961. Congress

attempted to confer the Medal of Honor but was blocked by the

stringent requirements that required heroism performed under fire.

The special medal was intended to have the same weight and importance

as the Medal of Honor.”

The heroism of the

Four Immortal Chaplains came to symbolize the meaning of America.

Their sacrifice exemplified the finest ideals of American freedom of

religion, toleration and commonality as Americans of all colors,

religions, and backgrounds fought to destroy the evils of fascism,

totalitarianism and Nazism.

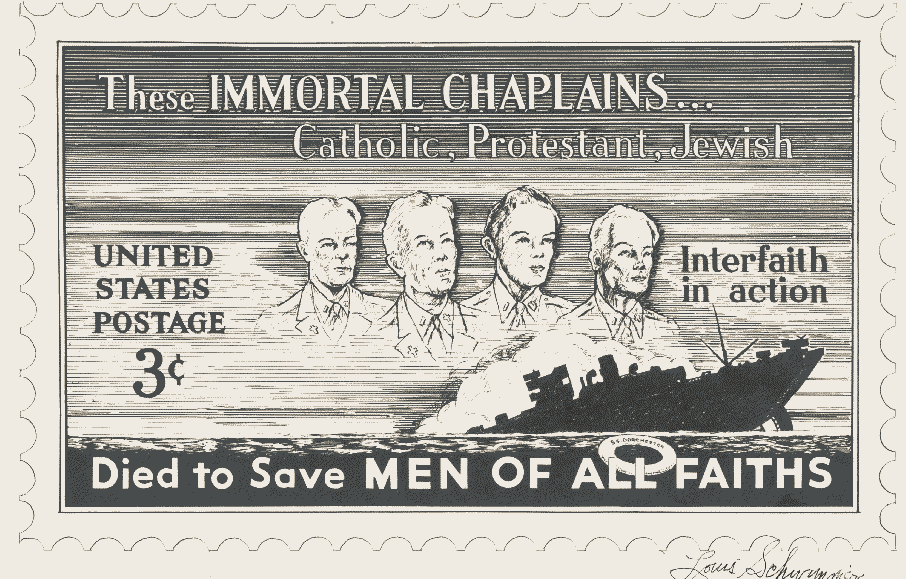

In 1947, New York

Postmaster Albert Goldman approached his chief artistic designer, an

orthodox Jew, Louis Schwimmer, to create a stamp honoring the Four

Chaplains.

Schwimmer thought the idea for the stamp originated with the

National Conference of Christians and Jews. It did not. The stamp

was the idea of a Jewish woman waiting in an anteroom to see

Postmaster Goldman, Claire A. Wolfe. Sol Glass, himself a Bureau

Specialist, quoted her story in his Postal Service history article,

Four Chaplains Commemorative Stamp, September 1948, Volume XIX,

No. 9.

"It was

Wednesday, November 27, 1947, and I was sitting in the anteroom

outside the offices of Postmaster Goldman in New York. As Public

Relations Counsel for the "Interfaith in Action Committee"

I had come to the Postmaster for some personal information in

connection with a testimonial dinner held in his honor.

"So I sat there

in the waiting-room reviewing in my mind the plans for the dinner and

striving for some new creative idea or symbol that would express the

work of my interfaith friends in terms the public would understand.

"I'm glad that

Postmaster Goldman was very busy that morning and therefore kept me

waiting a long time. What specific picture or slogan, I wondered will

tell in an instant the story of "Interfaith in Action?"

"Then

I remembered my friend, Irving Geist, the philanthropist, and the

invaluable contributions he had made in the Four Chaplains

organization to help paraplegics.

"THE FOUR

CHAPLAINS. That was it. What better symbol of Interfaith in Action?

"Four immortal

men - Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish - who gave their life jackets

to soldiers aboard the sinking transport U.S.S. Dorchester, in

February 1943. Four men of different faiths who locked their arm

together on the slanting, slippery deck until the waters closed over

them and made them immortal.

Suddenly Postmaster

Goldman was looking down at me and smiling. "I've got it."

I said excitedly, "A idea for a new postage stamp. A real symbol

of Interfaith in Action that people will understand."

"Yes,

indeed", said Postmaster Goldman when he had heard the idea.

"Putting the Four Martyred Chaplains on a postage stamp should

serve to inspire every man, woman, and child to practice

inter-religious and inter-racial cooperation. The rest was efficient

Post Office routine. Postmaster Goldman started the machinery working

and the Four Chaplains stamp was issued on May 28th, 1948"

The stamp was most

likely the first time in American postal history that a stamp was

conceived, designed and advanced to issue by Jews.

A

made for T.V. movie was produced in 2004, The

Four Chaplains, Sacrifice at Sea.

Thousands of articles have been

written about the Four Chaplains. Memorial markers and stained glass

windows adorning chapels, including the American Military Academy of

West Point, exist across the country. Governors of American States

issue annual proclamations in honor of the Four Chaplains.

The Episcopal Church has added a special memorial day of prayer and

remembrance to the Four Chaplains in their annual observances. A

historical memorial sits opposite the infamous Watergate Complex on

the Potomac River in Washington, D.C.

Five

years ago, Ken Kraetzer, the son of a World War II veteran and the

host of a weekly military focused radio show at Station WVOX in New

Rochelle, New York, went to do research on the Four Chaplains at

Arlington, National Cemetery.

Custis-Lee

Mansion Arlington, National Cemetery

Arlington National

Cemetery was created during the American Civil War to spite the famed

Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Lee’s home and farm were

located directly across the river from Washington in Arlington,

Virginia. “The property was confiscated by the federal

government when property taxes levied against Arlington estate were

not paid in person by Mrs. Lee. The property was offered for public

sale Jan. 11, 1864, and was purchased by a tax commissioner for

‘government use, for war, military, charitable and educational

purposes.’

Arlington National

Cemetery was established by Brig. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, who

commanded the garrison at Arlington House, appropriated the grounds

June 15, 1864, for use as a military cemetery. His intention was to

render the house uninhabitable should the Lee family ever attempt to

return. A stone and masonry burial vault in the rose garden, 20 feet

wide and 10 feet deep, and containing the remains of 1,800 Bull Run

casualties, was among the first monuments to Union dead erected under

Meigs' orders. Meigs himself was later buried within 100 yards of

Arlington House with his wife, father and son; the final statement to

his original order.

The federal

government dedicated a model community for freed slaves, Freedman's

Village, near the current Memorial Amphitheater, on Dec. 4, 1863.

More than 1,100 freed slaves were given land by the government, where

they farmed and lived during and after the Civil War.

Neither Robert E.

Lee, nor his wife, as title holder, ever attempted to publicly

recover control of Arlington House. They were buried at Washington

University (later renamed Washington and Lee University) where Lee

had served as president. The couple never returned to the home George

Washington Parke Custis had built and treasured. After Gen. Lee's

death in 1870, George Washington Custis Lee brought an action for

ejectment in the Circuit Court of Alexandria (today Arlington)

County, Va. Custis Lee, as eldest son of Gen. and Mrs. Lee, claimed

that the land had been illegally confiscated and that, according to

his grandfather's will, he was the legal owner. In December 1882, the

U.S. Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision, returned the property to

Custis Lee, stating that it had been confiscated without due process

On March 3, 1883,

the Congress purchased the property from Lee for $150,000. It became

a military reservation and Freedman's Village ceased to exist;

however, the gravesites that were once part of the village remained

on the grounds of the reservation.”

From the Custis-Lee

Mansion there is a clear view of the Lincoln Memorial, the Washington

Memorial and the United States Capital Building. Arlington Cemetery

is the resting place of the Tombs of the Unknown Soldiers. It is a

deeply emotional place, a very humbling place to stand amongst the

over 250,000 Americans, and a few non-Americans, who have given so

much for America and freedom. In a sense it is a place of the living

history of the United States. Men and women from America’s

struggles, ranging from the Civil War to the contemporary fight

against modern religious fascists in Iraq and Afghanistan, are buried

there. Memorials tell the story of America, from the simple

soldier’s headstone to the Mast from the sunken American war

ship the Maine. The Maine mysteriously blew up in

Havana, Cuba’s harbor igniting the Spanish American War. 212

men died on the Maine, fifteen were Jews. A large monument to

Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders stands quietly by the

side of a cemetery section. The first casualty of the famous Rough

Riders was a 16 year old Jewish volunteer, Jacob Wilbursky.

Arlington Cemetery

is a place of quiet rest and living history testifying to the meaning

of America.

There is a prominent

knoll above the intersection of McClellan and Grant Avenues in

Arlington. The knoll is named Chaplain’s Hill. On the knoll

are buried Chaplains from the U.S. Armed Services. Three large

memorial stone markers, seven feet high, with brass plates recognizes

the names of American Chaplains who died in America’s service.

The first marker was created in 1926 honoring the memory of World

War I Protestant Chaplains. A second marker for Protestant Chaplains

and finally a memorial marker for Catholic Chaplains were added.

Chaplain’s

Hill

Kreitzer went to

Chaplain’s Hill and quickly located the names of Chaplains Fox,

Washington and Poling. Any mention of or memorial for Rabbi

Alexander Goode was not to be found on Chaplain’s Hill. There

was no memorial stone remembering or respecting, the sacrifice of

Jewish American Chaplains on Chaplain’s Hill. Thirteen

American Jewish Chaplains had given their lives in service to

America.

Kreitzer stood there

looking at the memorials and thought “this is wrong.”

He resolved to correct what should have been done a long time ago.

Kreitzer is not Jewish. He is Catholic.

American

Freedom was not always as free as it is today. Freedom was and is a

developing process. For Jews, frequently, it was and sometimes still

is necessary to enlist the aid of non-Jews to protest infringements

upon American Jewish freedoms.

In

the early years of the American Republic it was non-Jews who

independently took up the struggle for Jewish rights. They did what

they did not just because it was the right thing to do but because it

was also in the idealistic interest of the unique new experiment

being born, the United States of America.

One

of the most distasteful vestiges of British Colonial rule were Test

Oaths. To vote and hold elected office, a Colonial citizen had to

swear upon their faith as a Christian, that they would uphold the

laws of their Colony. Jews, Quakers, atheists and other non-believing

individuals would be automatically and deliberately excluded from

equal rights. They could not take an oath that would perjure

themselves.

Virginia

became the first State to grant religious and political freedom to

all. Jefferson frequently quoted John Locke's argument that "neither

Pagan nor Mohammedan nor Jew ought to be excluded from the civil

rights of the Commonwealth because of his religion."

It

wasn't that Jefferson favored Judaism but rather he believed that the

free flow of ideas would in time lead to the triumph of Christianity

over Judaism. The Constitution of the United States was ratified in

1787 and the Bill of Rights was amended to it in 1791. The issue of

religious discrimination for Christians would become moot. Within a

few years, one by one the States changed their constitutions.

The

Western frontier state of Tennessee's compromise, an affirmation of

faith, typified the new, more tolerant standard, "no person who

denies the being of God, of future state of rewards and punishments,

shall hold any office in the civil department of State." The

very concept of religious test oaths, as the frontier pushed west,

became increasingly foreign. They were not incorporated into state

constitutions. The flow of new ideas of freedom tended to flow from

west to east. One state among the original 13 clung to its old

religious test ideals and fought bitterly to keep Jews in particular

from elected or State appointed offices – Maryland. The

struggle for freedom in Maryland was to be known as the JEW BILL.

The

first know Jew came to Maryland in the 1640's, Jacob Lumbrozo. It was

not until the middle of the 18th

century that Jews began to establish themselves as family units

settling primarily in the mercantile community of Baltimore. By the

time of the revolution they were integral members of the business

community. Baltimore over the next century was to become a major

center of Jewish life in America. Reuben Etting, a major supporter of

President Thomas Jefferson, was appointed by Jefferson as the U.S.

Marshall for Maryland in 1801. Etting was the first Jew to be

appointed to a major U.S. governmental position. Yet Etting could not

even be elected dog catcher in his own State of Maryland because of

the test oath requirements.

A

Maryland elected official had to swear upon his faith as a Christian

that he would uphold the laws of the State of Maryland. A Jew making

that declaration was lying and was automatically excluded from

holding office. For a Jew to hold elected office in Maryland the

Constitution of the State had to be changed.

As

the bombs burst throughout the night in the attack on Fort McHenry

during the War of 1812, Frances Scott Key watched. The next morning

the American flag still stood tall and proud. Inspired he wrote the

American National anthem based upon that scene. Little did he know

that within the walls of the Fort were Jews from Baltimore who were

defending it.

Seventeen

years after the Etting affair, a Scotch Presbyterian immigrant named

Thomas Kennedy was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates from

Western Maryland. Kennedy an ardent believer in Jeffersonian

Republicanism had never known or for that matter had never met a Jew

in his life. In the State legislature in Annapolis, Maryland he

learned of the political denial of rights to Jews, non –

conformist Christians, Quakers, and atheists. He recognized that a

denial of rights to one group was a denial of rights to all.

Kennedy

dedicated his political career and his political life to changing the

law in what became known as the Jew Bill of Maryland. For eight years

he began what at first was a lonely struggle. It was soon picked up

and championed by other Western Maryland legislators. The ebb and

flow of the fight for the Jew Bill was among the single ugliest

political struggles in Maryland history. Charges and campaigns of

anti-Semitism and anti-Christian cries resounded from one of the

State to another.

Kennedy

was to be defeated for reelection by his anti-Jewish political

enemies. The banner of Jewish freedom fell from Kennedy's hands. It

was picked up and carried by another Western delegate from Washington

County, Col. Worthington. By the narrowest of margins, one vote, the

Jew Bill was passed. In 1826 the Constitution of Maryland was

changed. Jews could hold elected office. With the legislature of

1828, Reuben Etting was elected from the city of Baltimore, to the

Maryland House of Delegates.

The

struggle was the ugliest in Maryland but it was no less a struggle in

other States. As late as 1824 Massachusetts refused to do away with

its own Christian test oath rather than give Jews the right to hold

elected office there. No less than the prestige of the former

President of the United States, John Adams, was brought to bear in an

attempt to change the law, only to be defeated.

After

the Jew Bill of Maryland denial of political equality for Jews was

never again a major issue. Jews were still socially and economically

discriminated against but never again via the Constitution of a new

State.

“At

the outbreak of the Civil War, Jews could not serve as chaplains in

the U.S. armed forces. When the war commenced in 1861, Jews enlisted

in both the Union and Confederate armies. The Northern Congress

adopted a bill in July of 1861 that permitted each regiment's

commander, on a vote of his field officers, to appoint a regimental

chaplain so long as he was "a regularly ordained minister of

some Christian denomination."

Only Representative

Clement L. Vallandigham of Ohio, a non-Jew, protested that this

clause discriminated against soldiers of the Jewish faith.

Vallandigham argued that the Jewish population of the United States,

"whose adherents are . . . good citizens and as true patriots as

any in this country," deserved to have rabbis minister to Jewish

soldiers.

Vallandigham thought

the law, which endorsed Christianity as the official religion of the

United States, was blatantly unconstitutional. However, there was no

organized national Jewish protest to support Vallandigham and the

bill sailed through Congress.

Three months later,

a YMCA worker visiting the field camp of a Pennsylvania regiment

known as "Cameron's Dragoons" discovered to his horror that

the officers had elected a Jew, Michael Allen, as regimental

chaplain. While not an ordained rabbi, Allen was fluent in the

Portuguese minhag (ritual) and taught at the Philadelphia Hebrew

Education Society. As Allen was neither a Christian nor an ordained

minister, the YMCA representative filed a formal complaint with the

Army. Obeying the recently enacted law, the Army forced Allen to

resign his post.

Hoping to create a

test case based strictly on a chaplain's religion and not his lack of

ordination, Colonel Max Friedman and the officers of the Cameron's

Dragoons then elected an ordained rabbi, the Reverend Arnold Fischel

of New York's Congregation Shearith Israel, to serve as regimental

chaplain-designate. When Fischel, a Dutch immigrant, applied for

certification as chaplain, the Secretary of War, none other than

Simon Cameron, for whom the Dragoons were named, complied with the

law and rejected Fischel's application.

Fischel's rejection

stimulated American Jewry to action. The American Jewish press let

its readership know that Congress had limited the chaplaincy to those

who were Christians and argued for equal treatment for Judaism before

the law. This initiative by the Jewish press irritated a handful of

Christian organizations, including the YMCA, which resolved to lobby

Congress against the appointment of Jewish chaplains.

To counter their

efforts, the Board of Delegates of American Israelites, one of the

earliest Jewish communal defense agencies, recruited Reverend Fischel

to live in Washington, minister to wounded Jewish soldiers in that

city's military hospitals and lobby President Abraham Lincoln to

reverse the chaplaincy law. Although today several national Jewish

organizations employ representatives to make their voices heard in

Washington; Fischel's mission was the first such undertaking of this

type.

Armed with letters

of introduction from Jewish and non-Jewish political leaders, Fischel

met on December 11, 1861 with President Lincoln to press the case for

Jewish chaplains. Fischel explained to Lincoln that, unlike many

others who were waiting to see the president that day, he came not to

seek political office, but to "contend for the principle of

religious liberty, for the constitutional rights of the Jewish

community, and for the welfare of the Jewish volunteers."

According to

Fischel, Lincoln asked questions about the chaplaincy issues, "fully

admitted the justice of my remarks . . . and agreed that something

ought to be done to meet this case." Lincoln promised Fischel

that he would submit a new law to Congress "broad enough to

cover what is desired by you in behalf of the Israelites."

Lincoln kept his

word, and seven months later, on July 17, 1862, Congress finally

adopted Lincoln's proposed amendments to the chaplaincy law to allow

"the appointment of brigade chaplains of the Catholic,

Protestant and Jewish religions." In historian Bertram Korn's

opinion, Fischel's "patience and persistence, his unselfishness

and consecration ... won for American Jewry the first major victory

of a specifically Jewish nature . . . on a matter touching the

Federal government."

Korn

concluded, "Because there were Jews in the land who cherished

the equality granted them in the Constitution, the practice of that

equality was assured, not only for Jews, but for all minority

religious groups."

President

Ulysses S. Grant

Abraham Lincoln interceded on behalf of Jewish Americans again

a year later.

“In

1862, in the heat of the Civil War, General Ulysses S. Grant

initiated one of the most blatant official episodes of anti-Semitism

in 19th-century American history. In December of that year, Grant

issued his infamous General

Order No. 11, which expelled all Jews from

Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi:

The Jews, as a class

violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury

Department and also department orders, are hereby expelled from the

department [the "Department of the Tennessee," an

administrative district of the Union Army of occupation composed of

Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi] within twenty-four hours from

the receipt of this order.

Post commanders will

see to it that all of this class of people be furnished passes and

required to leave, and any one returning after such notification will

be arrested and held in confinement until an opportunity occurs of

sending them out as prisoners, unless furnished with permit from

headquarters. No passes will be given these people to visit

headquarters for the purpose of making personal application of trade

permits.

The immediate cause

of the expulsion was the raging black market in Southern cotton.

Although enemies in war, the North and South remained dependent on

each other economically. Northern textile mills needed Southern

cotton. The Union Army itself used Southern cotton in its tents and

uniforms. Although the Union military command preferred an outright

ban on trade, President Lincoln decided to allow limited trade in

Southern cotton.

To

control that trade, Lincoln insisted it be licensed by the Treasury

Department and the army. As commander of the Department of the

Tennessee, Grant was charged with issuing trade licenses in his area.

As cotton prices soared in the North, unlicensed traders bribed Union

officers to allow them to buy Southern cotton without a permit. As

one exasperated correspondent told the Secretary of War, ‘Every

colonel, captain or quartermaster is in a secret partnership with

some operator in cotton; every soldier dreams of adding a bale of

cotton to his monthly pay.’

In the fall of 1862,

Grant's headquarters were besieged by merchants seeking trade

permits. When Grant's own father appeared one day seeking trade

licenses for a group of Cincinnati merchants, some of whom were Jews,

Grant's frustration overflowed.

A handful of the

illegal traders were Jews, although the great majority were not. In

the emotional climate of the war zone, ancient prejudices flourished.

The terms “Jew,” “profiteer,” “speculator”

and “trader” were employed interchangeably. Union

commanding General Henry W. Halleck linked “traitors and Jew

peddlers.” Grant shared Halleck's mentality, describing “the

Israelites” as “an intolerable nuisance.”

In November 1862,

convinced that the black market in cotton was organized “mostly

by Jews and other unprincipled traders,” Grant ordered that “no

Jews are to be permitted to travel on the railroad southward [into

the Department of the Tennessee] from any point,” nor were they

to be granted trade licenses. When illegal trading continued, Grant

issued Order No. 11 on December 17, 1862.

Subordinates

enforced the order at once in the area surrounding Grant's

headquarters in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Some Jewish traders had

to trudge 40 miles on foot to evacuate the area. In Paducah,

Kentucky, military officials gave the town's 30 Jewish families—all

long-term residents, none of them speculators and at least two of

them Union Army veterans—24 hours to leave.

A group of Paducah's

Jewish merchants, led by Cesar Kaskel, dispatched an indignant

telegram to President Lincoln, condemning Grant's order as an

“enormous outrage on all laws and humanity, ... the grossest

violation of the Constitution and our rights as good citizens under

it.” Jewish leaders organized protest rallies in St. Louis,

Louisville and Cincinnati, and telegrams reached the White House from

the Jewish communities of Chicago, New York and Philadelphia.

Cesar Kaskel arrived

in Washington on Jan. 3, 1863, two days after the Emancipation

Proclamation went into effect. There he conferred with influential

Jewish Republican Adolphus Solomons, then went with a Cincinnati

congressman, John A. Gurley, directly to the White House. Lincoln

received them promptly and studied Kaskel's copies of General Order

No. 11 and the specific order expelling Kaskel from Paducah. The

President told Halleck to have Grant revoke General Order No. 11,

which he did in the following message:

A

paper purporting

to be General Orders, No. 11, issued by you December 17, has been

presented here. By its terms, it expels (sic) all Jews from your

department. If

such an order has been issued, it

will be immediately revoked.

Grant revoked the

order three days later.

0n January 6, a

delegation led by Rabbi Isaac M. Wise of Cincinnati, called on

Lincoln to express its gratitude that the order had been rescinded.

Lincoln received them cordially expressed surprise that Grant had

issued such a command and stated his conviction that “to

condemn a class is, to say the least, to wrong the good with the

bad.” He drew no distinction between Jew and Gentile, the

president said, and would allow no American to be wronged because of

his religious affiliation.

After

the war, Grant transcended his anti-Semitic reputation. He carried

the Jewish vote in the presidential election of 1868 and named

several Jews to high office. But General Order No. 11 remains a

blight on the military career of the general who saved the Union.”

Whether

Grant was anti-Semitic or he simply signed an order without being

fully cognizant of its contents and implications has been argued

repeatedly over the years. What is factual is that as President,

Grant was a friend to Jews and Jewish concerns. He was the first

president to attend the dedication of a Jewish house of worship, Adas

Israel in Washington, D.C. He firmly placed American support against

the rabid anti-Semitism of Russia and appointed Jews to high office.

Jews responded to Grant with overwhelming electoral support.

General

Wingate

On

Grant Avenue, a few hundred yards away from Chaplain’s Hill, is

the gravesite of British Major General Orde Wingate. Wingate, an

ardent supporter of Zionism and the Jewish right of self defense in

Palestine, is largely credited as one of the founding fathers of the

Israel Defense Forces. Wingate’s remains were retrieved from

the jungle crash site of his American transport plane shot down in

Burma during World War II. They were indistinguishable from the

American crew’s. They were all brought back and reinterred in

Arlington National Cemetery.

Independent

of any urgings from any Jew or Jewish organization, Kreitzer knew

that Goode’s name deserved to be among the honored Chaplains on

Chaplain Hill. He knew that Jews, as Americans in common with their

Christian fellow citizens, deserved proper and fair recognition for

their service and sacrifice. Kreitzer contacted the Jewish War

Veterans of America in Washington, D.C. They arranged for Kreitzer

to meet with -Rabbi Harold L. Robinson.

Rabbi Robinson was a recently retired Rear Admiral in the United

States Navy. He had been the highest ranking Jew in the American

Armed Forces and the man in charge of all Chaplains when he was on

active service.

Kreitzer

and Rabbi Robinson united in common effort to correct what had been a

long “oversight.” Their joint efforts quickly raised

support from Jewish and non-Jewish organizations nationwide. A

petition supporting the project was begun. Voluntary subscriptions

provided the funding necessary for an expanded marker project. The

objective was to erect, on Chaplains Hill, a fourth monument that

would carry Rabbi Goode’s name but also the 12 other names of

American Jewish Chaplains who have died in service to America. A

brass marker was designed and approved by the Fine Arts Commission.

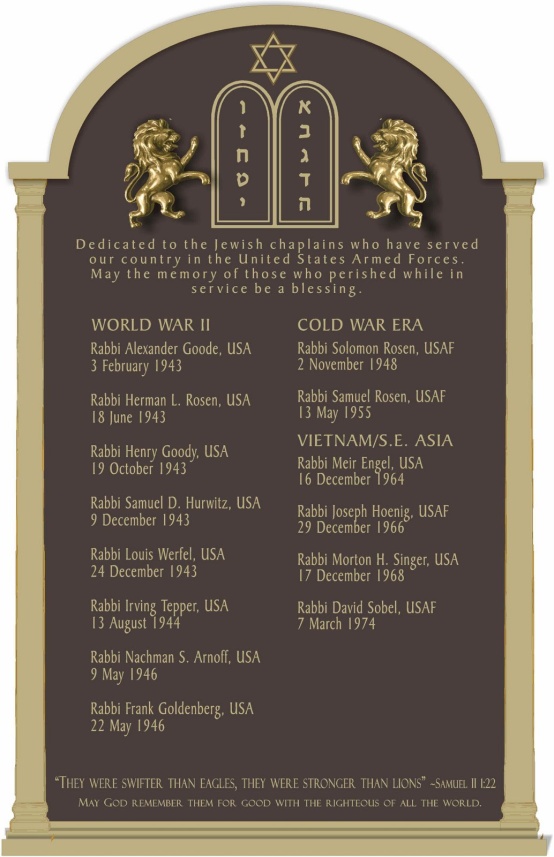

Jewish

brass Marker for Chaplains Hill

The

effort labored on, for almost five years without success. The

administrators of Arlington National Cemetery placed one more major

hurtle before Kreitzer, Rabbi Robinson and their supporters. Because

of an administrative scandal at Arlington in the 1980’s,

Congress passed a law that no new memorials could be erected without

Congressional approval. The administrators required a Congressional

Resolution passed by both House of Congress affirming the effort to

erect a fourth monument on Chaplains Hill for Jewish Service Men and

Women.

The

frustrating administrative logjam was finally broken this year.

Congressional resolutions in favor of the historic memorial marker

for Chaplain’s Hill were introduced. House Congressional

Resolution # 12 was introduced under the leadership of New York

Congressman Anthony Weiner (D) and Florida Congressman Tom Rooney (R)

along with 82 co-House sponsors, January 25, 2011. “Expressing

the sense of Congress that an appropriate site on Chaplains Hill in

Arlington National Cemetery should be provided for a memorial marker

to honor the memory of the Jewish chaplains who died while on active

duty in the Armed Forces of the United States.”

Senate

Congressional Resolution # 4 was introduced, January 26, 2011, under

the leadership of New York Senator Charles Schumer along with 27

co-Senate sponsors. “A concurrent

resolution expressing the sense of Congress that an appropriate site

on Chaplains Hill in Arlington National Cemetery should be provided

for a memorial marker to honor the memory of the Jewish chaplains who

died while on active duty in the Armed Forces of the United States.”

May

27, 2011 the resolution was approved by the United States Congress.

June 24, 2011 the project to erect a memorial for Jewish Chaplains on

Chaplains Hill was referred to the Subcommittee on Disability

Assistance and Memorial Affairs.

Speaking

with Ken Kreitzer and being in contact with Rabbi Robinson a few days

ago, they shared some of the elaborate plans being worked on for the

dedication. They envision the plaque will tour American cities from

Boston to Florida before returning to Arlington for installation on

the memorial stone on Chaplain’s Hill.

Almost

68 years after his death, Rabbi Goode will finally be recognized at

Arlington National Cemetery. Rabbi Goode was born in New York to

Rabbi Hyman Goodekowitz. He grew up in the tight knit small

Washington, D.C. Jewish community. He attended Eastern High School

where he was a star football player. Goode went on to study at

Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati coming back to Washington in the

summers, before his ordination, to work at the Washington Hebrew

Congregation. Good married a niece of famed American popular music

personality Al Jolson both of whom had been Washingtonians. Before

being shipped out, Goode was affronted by anti-Semitism but it did

not deter him from doing his duty as an American.

October

24, 2011, on Chaplain’s Hill, a long, long overdue historic

marker will be dedicated remembering and honoring not just Lt., Rabbi

Goode of the U.S. Army but also 12 other American Jewish Chaplains

who gave their all for America. It will be the 150th

anniversary of American Jews as chaplains in the United States Armed

Forces.

Jerry

Klinger is President of the Jewish American Society for Historic

Preservation.

www.Jashp.org

He

can be contacted at Jashp1@msn.com

|